The land beyond the tarns

Romania's battle with the Danube

Between Baziaș and Gura Sulinei, the Danube caresses the Romanian shores for 1,075 kilometers. In its flow through our lands, the river has given birth to a paradise that our ancestors called the Danube Plain. A space where the Danube used to pulsate seasonally, giving substance to its inner life, animated by more or less scaly jivines, bird wings and chlorophyll. From the net to the plough, from the carp to the wheat ear, the Danube Romanians understood that the bounty of the waters must be respected as God left it. Between the poverty of today's dryness and the richness of the smorgas over a hundred years ago there is the story of the Romanian's struggle for paradise by diking. It's not that we don't have enough land to farm as far as the Bărăgan with your eye's eye to the horizon. It is just a matter of the frenzy of destruction in the name of the good and the voluptuousness of realizing the disaster we are bequeathing to future generations under the Romanian saying "Atât s-a putut".

The Romanian struggle with the Danube

The first dyking work took place in 1895 in the Danube Delta at Mahmudia. It didn't turn out as the farmers expected, but the fishermen didn't mind either, as there was water and fish for everyone. Then, in 1904, there were other dykes in the Danube Plain (Chirnogi, Mănăstirea, Giurgeni), where corn won the battle with the water lily. There were still no "destuffing" chemicals, no pesticides. The sludge was filled from the simple biology of the nutrient-rich soil and held magically for a few years until the sludge poverty surfaced. Around 1910, a law was also passed to "valorize" flood plains, which had the great advantage of being near water and not risking the disasters of the Bărăgan's land, made in times of drought. Anghel Saligni also intervened, who had the engineering vision of dyking the entire Danube floodplain. It sounded good at the time, including for the inhabitants of those areas, for whom the mirage of the rich holdings and the transformation of spring days - with the Danube seeping through their nightdresses - to become a damp nightmare, far removed. And let's not forget that, in addition to daily bread, fish was the poor man's food in those days, and black roe was eaten in the bordei, as an appetizer for the 'organic' duck or duck with a "organic" version of the duck. There was still the pond.

The hammer and sickle

Then agriculture intervened scientifically, when Ghe. Ionescu Șișești carried out research between 1910 and 1913 and demonstrated the rich fertility of the dyked areas, which gave even more impetus to the desiccation. It was then time for Grigore Antipa to intervene on the agricultural scene and draw attention to the need for a balanced approach to wetland destruction. The floodplain destruction was at that time only limited by technological limits, so that it was expected that only the upper reaches of the Danube (about 130,000 hectares) would be drained, of which about 46,000 hectares were dammed between 1923 and 1944, and subsequently destroyed by periodic reversals. And the communists came.

The struggle of the proletariat against the bourgeoisie continued with a declared war of co-optation of nature. Ecology itself became an imperialist term. This is how desiccation became "man's struggle with nature", this is how it became state policy, and the ponds were doomed to become a field trampled by the wheels of tractors. If in 1949 the area under irrigation was 10,200 hectares, by 1969 corn and wheat were being sown on 395,000 hectares of land that had been wrested from the marshlands. By 1987, Ceausescu was already boasting 84% of the entire Romanian meadow area as being under water. Together with the draining of the Delta, this amounted to 479,000 hectares. In other words, an area equal to that of the entire delta, which gives us the right to say that we have already destroyed one delta along the Danube, and now we are dealing with a second one, located at the mouth of the Danube.

Nobody has considered how this major transformation will affect the climate, fish stocks, biodiversity and not least the life of the people around the Danube. We can see the results today: the dramatic drop in fish production after 1975, due to the disappearance of spawning grounds, and desertification in southern Romania, due to the disappearance of wetlands and the alteration of the hydrological regime. Last but not least, we are talking about a significant loss of biodiversity.

And so, one by one, the Deltas are disappearing

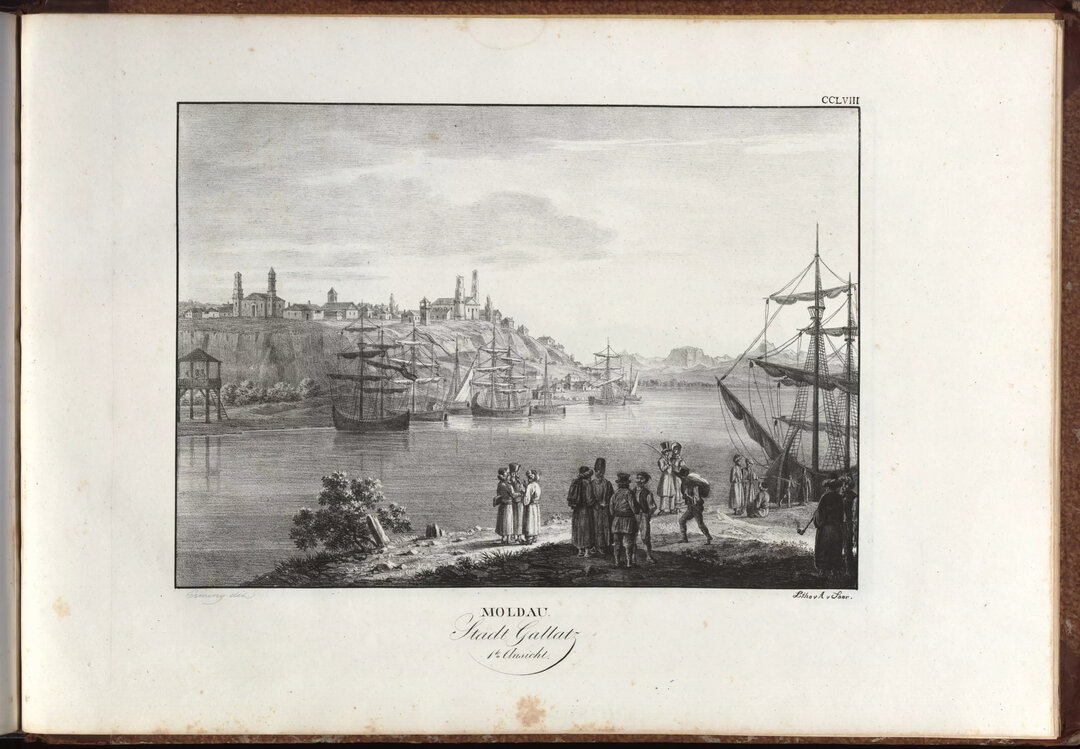

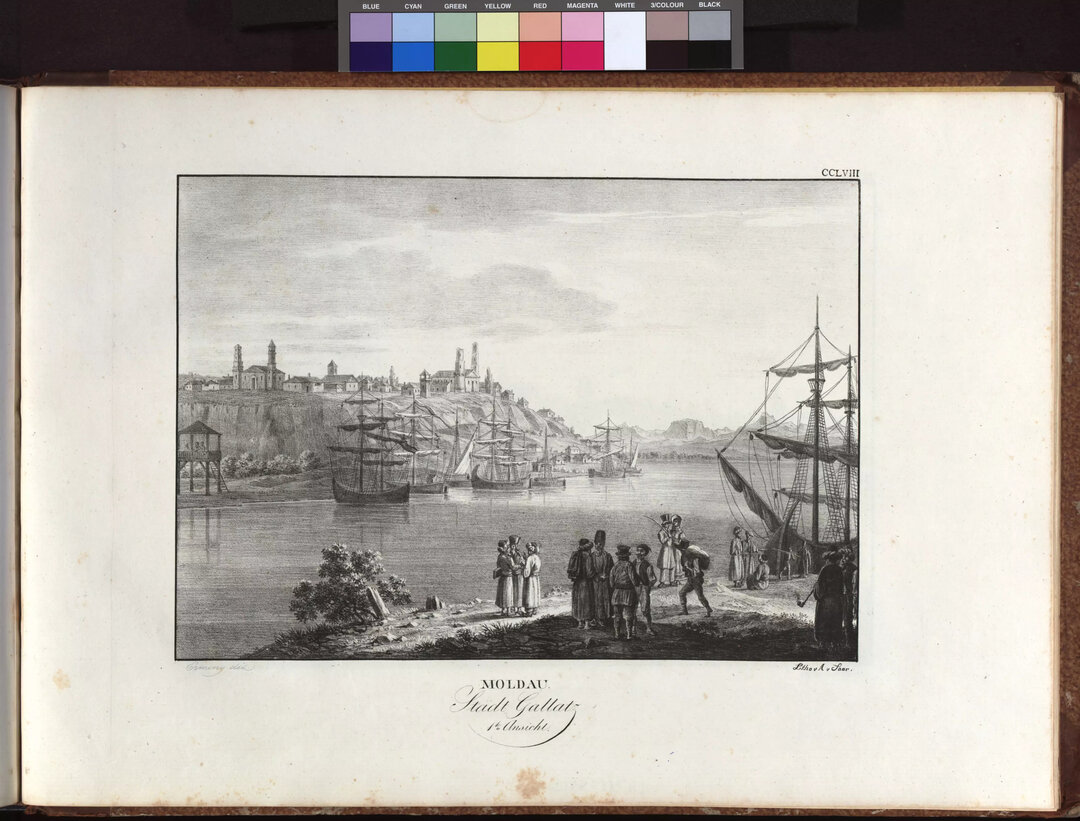

The damage had been done, and the nightmare of the wet islets has returned, because the disappearance of the flood plains where the high waters lose their strength, dissipating over thousands of hectares of meadow, the flood wave is amplified due to the stratification, causing catastrophic floods, as happened in 2006. To understand how we have managed to destroy the balance of the river, a balance which has also shaped the local climate, let's take the example of Lake Brateș, near Galati. One hundred years ago, it covered an area of 27,000 hectares, with a biodiversity unimaginable anywhere else, enough fish to feed the whole continent, not just Galati. It was considered Romania's Balaton, until the 1950s when the "Ana Pauker" construction site was set up, so that when the work was finished, only 8,000 hectares of water were left in Brateș. A fish farm that went bankrupt in 1997. Even the farming has not fared any better, with impoverishment and soil depletion transforming the arable land so that the record yields of yesteryear have become a pale memory. What farmers don't understand is that a lake like Brateșul has been instrumental in providing ecosystem services best defined by a study by the Galati-based ECOGAL association. "Take for example an area of 5,000 ha that has become arable land. For 5,000 hectares under water, solar energy loses 16,176,000 gigacalories each year, equivalent to 18,810 Gigawatt-hours per year, to evaporate a water layer of 30 million cubic meters of water per year. Nature is thus investing 11,850,300,000 lei, or 2,548,451,451,600 euro, just with what is left of the former Brateș lake, giving Galati a bearable microclimate and some fish". Can you imagine, just from a climatic and piscicultural point of view, what would have been the eco-systemic service for the area of Galati if the Brateș Lake had not passed through the "Ana Pauker" site. "For more than half a century, arable land has been scorched with 18,810 GWh/year", Ecogal's Ecogal also say, and the inhabitants of Galati compensate for the locally amplified global warming with air conditioners. "It was an ecological crime as a result of which the people of Galati were left without this microclimate," conclude those who carried out the study.

Few may know that a second Romanian Delta exists in the south, with the Danube's meadow a patchwork of pools and flood gullies rivaling the Delta proper at the river's mouth. The Rast, Nedeia, Potelu, Suhaia and Mostiștea pools were dried up one by one. The jewel in the crown was the 7,400-hectare Greaca pond near Oltenița. In addition to its annual production of over 7,000 tons, Balta Greaca was a natural flow regulator, which attenuated the shock of the floods in the lower reaches of the Danube. But let's take them one at a time: if at that time only Balta Greaca had an annual production of 7,000 tons, today all the fish production reported by fisheries in our country is somewhere around 4,000 tons (Danube Delta, Danube, Olt, Siret). In other news, with nowhere to overflow in the spring after the snow melt and spring rains, squeezed between the dykes since entering the country, the Danube caused catastrophic flooding in 2006, when the authorities had to dynamite the dykes at Rast.

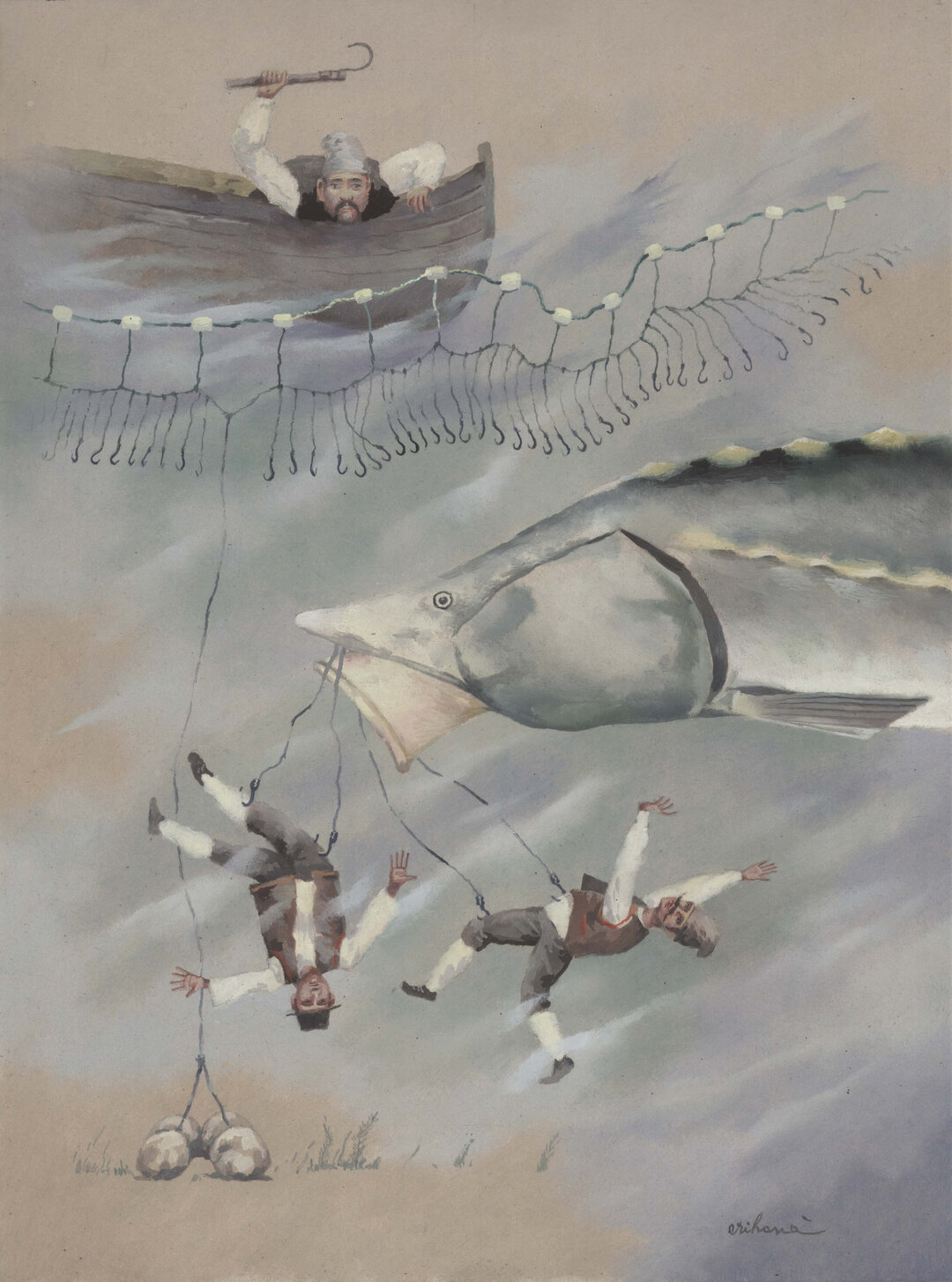

Story from Greek

I remember meeting an old fisherman in a village near Oltenița in the early 1980s who told me how he used to fish in Balta Greaca in spring, a shallow floodwater where all the fish species in the Danube, especially carp, used to spawn. Boats were tied up a few dozen meters from the shore, and you walked through the shallows to reach the nets. The boats were filled with fish, which were taken to a higher ground where a railroad line was built, where a marfar waited to load the harvest into barrels of ice. There were so many fish in the Greaca that the boats were unloaded until the boatman raised the red flag. That meant the train was full. The fishermen could have brought in fish for two more trains, but the fishing day ended with the red flag, when the boats were already half full with mixed roe and milt, drained from the bellies of the spawning fish being hauled to the train. The fishermen grabbed their shovels and emptied the boats into the water, emptying the milk and mixed roe, most likely ready fertilized between the boat's sieve. The next generation of fish would emerge from the spawn, which would return to the Danube with the waters of the Greek Baltic in early summer, when the Danube's water level dropped. This is how Bucharest was supplied with fresh fish from the Danube. For those who don't salivate at the smell of fried fish, there's another approach to what we lost: if the fish reached Bucharest fresh, the CFR was working. With CFR delays nowadays, Bucharest would have been left without fish.

Today, on the site of the former Greek Balti, where the pond used to embrace natural meadows and forests, there is a small field that is a closed hunting area, as well as partial arable land, with a lot of reeds and reeds. The loss should not only be calculated in tons of fish, the destruction of ecosystems and biodiversity, but also in profound climatic changes, effects which are already being felt.

About Braila's Balta Mare, without Terente

During the time of the People's Republic, the proletariat drained and dammed a natural wonder, a Nada of Flowers - Balta Mare a Brăilei - between 1950 and 1960. The Communists "gave" the pond back to agriculture, which became arable land, in the belief that swamps and marshes are useless and unhealthy anyway. The destruction of wetlands by reclamation did not take into account the patchwork of ecosystems here, and the Party heard only what it liked to hear from engineers and farmers, not from ichthyologists, biologists, fish farmers and hydrologists. No wonder Romania only joined the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands, established in 1975, in 1991, a year after the collapse of communism. In the scale of history, the place seems eternally haunted by the outlaw Terente. Murder and extortion in the pond became by desiccation murder and extortion in forced labor colonies, where Terente was reincarnated as a militiaman. The destruction of the natural and piscicultural paradise called Balta Mare a Brăilei was used for the forced labor of the political prisoners from the camps of Lunca, Grădina, Salcia, Vechea Strâmbă and Stoienești. Many of them left their bones in the dikes here, a custom perpetuated in the draining of the Tătaru area in the Delta, where agriculture in the Chiliei Field was

by the same dyking and draining. Here, too, the prisoners were killed by the famous Maromet through labor, starvation and beatings to be buried in the Periprava dam. Returning to our sheep in the floodplain sheepfolds, the annihilation of the Great Bar of Braila followed the natural course of all such works: initially the yields were absolute records, which led the regime of the time to declare this "ecocide" a "success of communism". The success became - after at most a decade of impregnating the soil with dozens of tons of "destuffing" poisons, nitrates and phosphates - a disaster through the natural impoverishment of the soil. The pond was taking its revenge, and even as the tractors continued to turn the clay, the paradox was most faithfully mirrored in the cracks yawning through the dry earth. The rains did not come often, and the place that once sheltered fish, birds and water lilies now had to be watered by irrigation systems. The Danube flowed back into the former Braila's Pond through motor pumps and sprinklers.

From better to worse

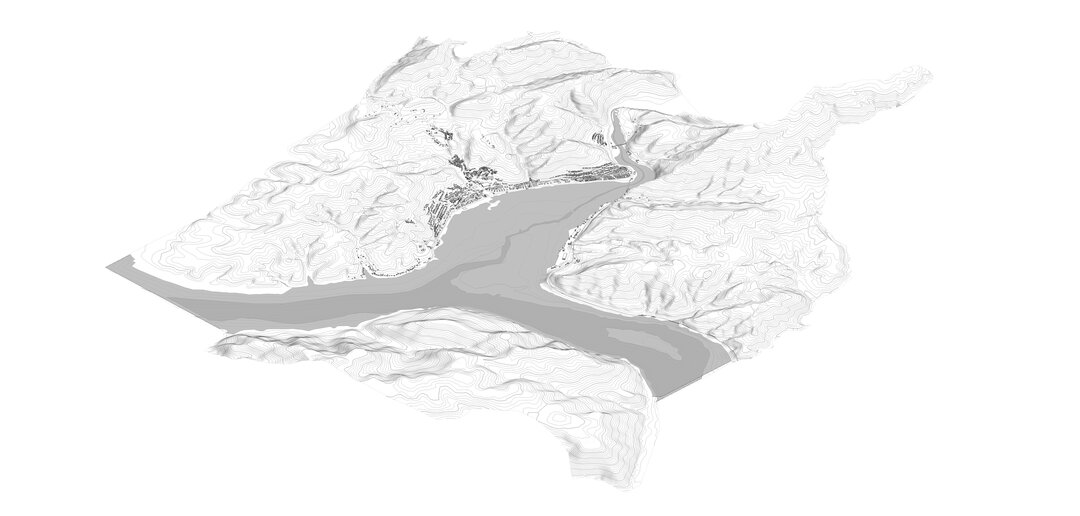

To understand what the dyking has destroyed, we need to paint the picture of Braila's Balta as it was before communism. Here is a landscape dominated by water in a dynamic regime, as the spring floods recede in early summer. There is a labyrinth of canals, gorges, marshes, ravines, reed thickets and meadow forests, and several navigable canals, of which Filipoiu and Ulmu are the most important. We have 63,190 ha in total, of which 11,629 ha are water meadows, and the remaining 51,560 ha are floodplain, reedbeds, willow forests. The largest quantities of fish per hectare in the whole history of Romanian fish farming were caught in the waters here, and on the land that emerged after the waters receded, seasonal agriculture was practiced, the nutrients in the soil ensuring high yields without considerable effort on the part of the farmers. It was a perfect natural system that functioned as soon as the spring floods came in through the network of canals leading to the main lakes (Șerbanul, Gemenele, Orzea, Rusava, Scurtul, Bobocul, Lungulețul, Dunărea Veche, etc.). The fish entered with the water and began to spawn, while the fishermen put fences of wicker on the canals through which the water flowed back to the Danube. As the water receded, the fish were caught on these fences, the eggs hatched and the fry passed back into the Danube. Braila's Balta Mare is not only a marvel of commercial fishing, but also a huge natural spawning station. Simply put, the network of canals looked like a vascular system in which the Danube was the heart pumping water through the Filipoiului and Corotisa gorges. Together with these waters, all the fish species that a treatise on ichthyology could cover were entering the pools and pools. It wasn't just quantity, it was biodiversity. It was richness.

Before Gr. Antipa was the Natural History Museum

This is what the great naturalist Gr. Antipa in 1910, the man who revolutionized fisheries in our country at the beginning of the century, about the Mare Balta of Braila, in his book The Floodable Region of the Danube:

"The water overflowing over the plains and through the willow forests where the fish feed and grow very fast, finding abundant food, begins little by little to recede from the marshes and from here through their drainage channels it flows into Filipoi. Little by little the fish also follows this path, wanting to go out into the Danube, so that when the waters recede, especially in the fall, a large part of the fish from the Domain is already concentrated in the Filipoiul channel. Here it is fished in enormous quantities - once I once observed alone in 3 hours catching 26,000 kg. The fishing of the pools with nets and birds begins in the fall, towards the end of August, the fish that remains here, frightened by the nets, flees from all sides and concentrates again in Filipoi (...) it tries to hide in the pits and under the willow stumps, but the fishermen find it and fish it on the one hand under the banks with the nets and on the other hand in the pits with the willows. On the one hand, the Braila's Domain's pond is a wonderful trap for catching fish from the Danube that come to it to reproduce, and at the same time it is a wonderful place where the fish reproduce, eat and grow, producing an enormous yield, unknown in other fisheries in Europe.

Ialomița, fresh water, it's all going. The same goes for Braila's Balta Mica

Balta Ialomița, a series of marshes, lakes, ponds, stretches of land covered with groves of forest, was for centuries the major riverbed of the Danube, where the river periodically overflowed with the spring floods. This is a gazetteer template, you will say, but we need to go further to understand this drama of nature and Romania's landscape heritage. Between 1960 and 1969, the Ialomița Bal was drained and dammed. As in other places dominated by puddles and lost to desiccation, in addition to the destruction of aquatic ecosystems and the loss of ecosystem services caused by the presence of wetlands, there are significant anthropological losses. Economically thriving settlements based on fishing, trade and alternative agriculture have disappeared, giving way to dusty agricultural fields. The villages of Hagieni, Brăilița, Bobu and Chioara, built on the old hearth of the Floci Town, were landmarks of economic and social development in this part of the Bărăgan. As early as the 1970s, the ecological and human disaster caused by the 'return' of these

to agriculture. In place of the old prosperity, the agricultural farm and the C.A.P. have brought more poverty than production. Today only a small part of the land is used for agricultural purposes, the rest is a vast wasteland where only the scaiete still carries chlorophyll from one generation to the next.

Following the principle of "Give the communist a foothold and he will destroy the whole universe", the massacre of the Ialomita Balti was accompanied at the same time by the reclamation of the Băltii Mici of Brăilei in 1964. In a short time, the 149,000 hectares of "puddle" were reduced fivefold by draining and diking, to 17,529 ha. Agriculture here has followed the pattern of all the meadow areas that have been dammed and "returned" to agriculture: a period of record yields, impoverishment and subsistence production. In 2000, what was left of the marsh became a reserve in which birds, fish, plants - and in general what else we can call the biodiversity of the Danube plain - find refuge. No, don't think that Romanians have come to their senses and started to restore and respect wetlands. For 30 years, renaturation projects have been blocked by politicians with vested interests in the agricultural concessions of the dammed areas.

Let there be renaturation, but let us know

The Danube Green Corridor is a project launched in 2006, costing 4 million dollars, which aims to renature and restore the lower part of the Danube Danube meadow, that is to say an area of 530,000 ha that would have been restored - this time the term is the correct one - to wetlands, as I said. Digital models, scenarios and simulations of managed floods, three-dimensional models, hydraulic models, maps, and the elevations of the levee canopies have been produced. A major work finalized by specialists in 2010, which was, however, lamentably modified by officials from the Ministry of the Environment and decapitated in Galati by a secretary of state, for economic "reasons". Economic reasons mean agricultural concessions and the economic interests of the concessionaires, who are invariably part of the political clientele of the Dâmbovițe or county. It is economic reasons that make politicians lose the use of reason.

So, in the name of a few concession profiteers, Romania has renounced the renaturalization of more than 85% of what was envisaged in the initial project, leaving only 15.9 of the agricultural areas to be renaturalized. As in a joke with Radio Yerevan, which says that the information is true, except that it was not "given" but "taken", the Danube Green Corridor had become an agricultural corridor. Of the 530,000 hectares originally earmarked for renaturation, 40.8% remained as polder agricultural land and another 43.3% as permanent agricultural land. The interests of the new landowners, the temporary owners of more than 110,000 ha of farms on the Danube plain, have also led to this ridiculous form of Green Corridor being postponed sine die.

The Baltic, Saudi land

Could this Romanian farmer's fight for renaturation, in the name of our daily bread, be a just and legitimate one? The example of Bălții Mari a Brăilei can be a case study, because it is the place that consecrated Triță Făniță as the great guru of agricultural concessions and cereal magician. We won't dwell on the multi-million euro tax evasions sprouting from the tractor-ravaged glia of the former Triță plowed marshlands and the productions heavily supported by state subsidies. So fast forward to 2018, when the 56,000 ha of arable land enters the economic harem of an Arab sheikh for €200,000, the value of just one of the SUV limousines in which he used to drive his camels home. The new farmer, who today commands his tractor divisions in Terente's ghost haunted lands, is honorary president of the Al Jazeera football club, a former minister and even prime minister of the United Arab Emirates. Chemicals and per-hectare subsidies have entered the Arab-Brab land like water into desert sand, so the Competition Council approves the merger of the Saudi sheikh's company with a Moroccan state-owned company specializing in the production of phosphate-based chemical fertilizers. We therefore have a successful recipe for the crossbreeding of communism and capitalism, which is taking man's struggle with nature further on Romanian soil.

It's not wheat that brings happiness, it's the desiccated hectares

The perpetuation of the disaster caused by the dyking of the Danube plain has a simple scheme, given by the political interests and the money being used to gain access to agricultural concessions in such areas. The next step, once in the shoes of the agricultural concessionaire, is not essentially to have agricultural production, but to access European funds and all kinds of subsidies per hectare for diesel and other farm accessories. For example, for an agricultural development on the scale of the one in the former Baltă a Brăilei, with 56,000 ha, it is enough that, exclusively through subsidies, it is a business in itself, production being just a bonus if you know how to do it, or rather how not to do it. The agricultural subsidizer thus becomes an important species in the new fauna populating the former wetlands of the Danube corridor, and the ecosystem would not be functional without the food chain at the end of which are the importers of food and grain, favored by the low efficiency of such farming. If the agricultural producer is dependent for his well-being on the area he manages through subsidies in order to produce high yields in theory - and I am only saying in theory - the importer is favored by the low yields of the domestic farmer. This symbiosis leads politicians and politicians in state institutions to prefer 'economic activities' and not the renaturation of the Danube plain, once a source of biodiversity and natural resources.

If before the damming and draining of the almost 500,000 hectares of floodplain, Romania was the breadbasket of Europe, and this only because of the generosity of the Bărăgan's chernozem, and also because it had the most important fishery in Europe - based exclusively on the Danube's fish richness, today we import 70% of our food needs in general and 80% of our fish needs in particular. This is the untold story of the desiccation of the Danube plain.

-topaz-denoise-enhance-sharpen--15883-m.jpg)