Facing the Danube

© Gyuri Ilinca

Civic and community activation

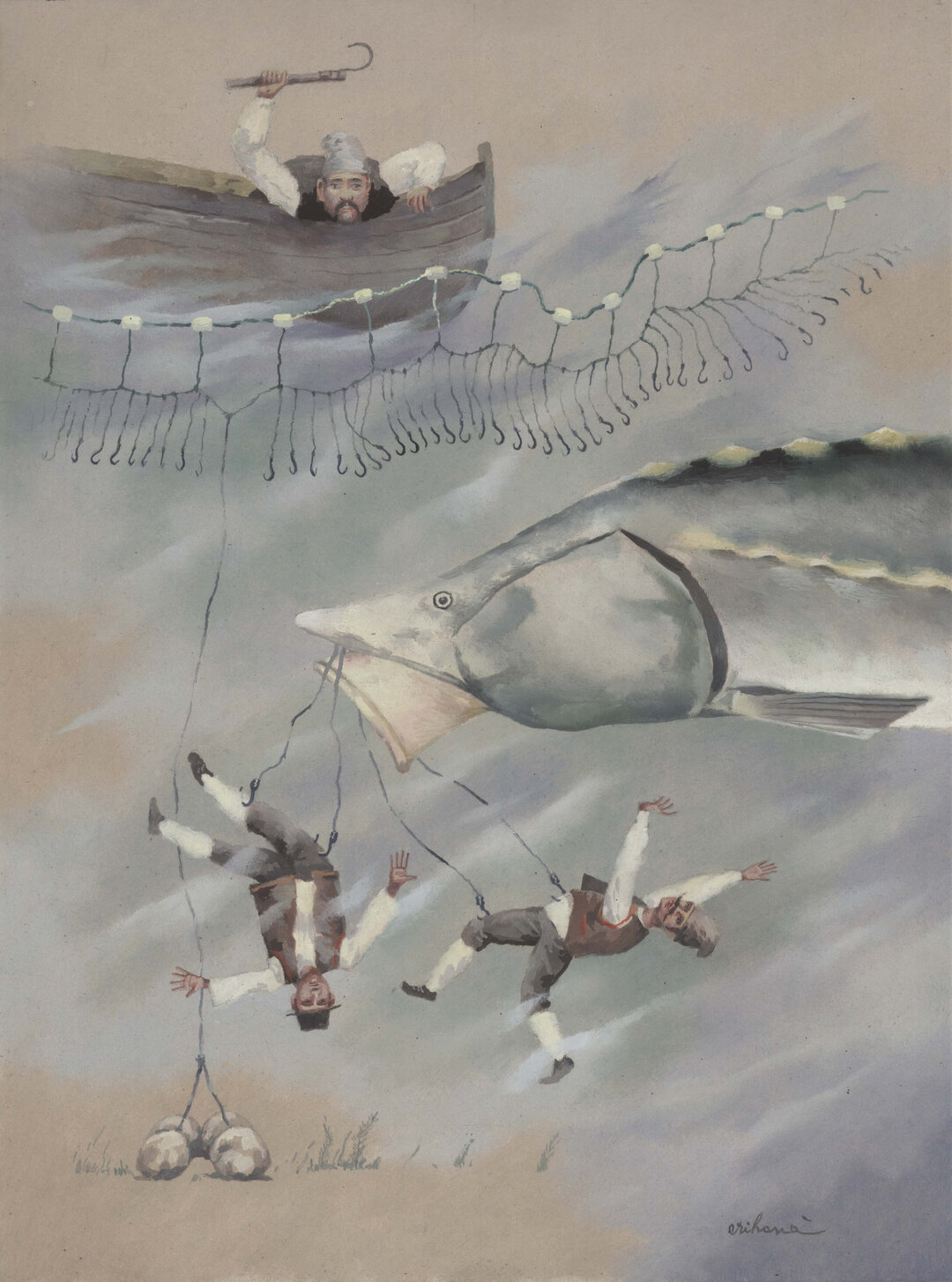

It is said that the Danube cities are positioned either facing or facing away from the Danube, depending on the orientation of the neighborhoods. The cities facing the Danube are perceived as welcoming, with open streets and waterfronts that allow the city to be seen by those who see it sailing on the Danube. Otherwise, the cities with their backs to the Danube have built their inner worlds away from the water, sheltering themselves between neighborhoods that block the view of the Danube.

The reality on the ground shows that the orientation of neighborhoods towards the Danube now says less about the city's desire to embrace the natural heritage of which it is a part and more about the diminishing economic importance the river has had for the city. Is this distancing, then, a self-prophecy for the complicated relationship the city has with its main heritage element?

In the last three years spent talking about, working in or thinking about Giurgiu, the city's relationship with the Danube has been a constant and perhaps the only source of certainty that this city can count on. We believe that there is also a social element at the heart of this categorization, namely how the city opens its local architectural and natural heritage to be known, appreciated and protected. Regardless of its urban planning history, there is hope for the social future of the city to turn its face towards the Danube.

But where do you start to turn the city around? On a physical level, urban regeneration projects, infrastructure investments, consolidation of commercial and residential areas, development of tourist offers are just some of the plans on the table of local authorities. The need for them is clear and indisputable, the question is when and with what priority. As in any scenario of urban transformation, the dilemma of the catalyst of change - community or investment - is also relevant for Giurgiu. Both are needed in parallel, with orchestration tailored to local needs. But whether you start with community activation or investment attraction, you start with people.

For a city like Giurgiu, in an economic and social impasse, people are an indispensable resource. People are those who can reconnect with the city, who can rediscover the desire for involvement and hope for a better future. It is also they who can find the resources and ways to make it happen. But for this, from citizens to civil servants, the people of Gigiu are looking for their place in a city in constant negotiation.

Giurgiu - the city in urban contraction

From a generic point of view, Giurgiu can mean its proximity to Bucharest (60 km), its location on the Danube border and a good regional positioning (Muntenia) on the Ploiești/ Bucharest/ Giurgiu axis. From a macro perspective, the positioning of the city is a key to its tourism potential due to its proximity to Ruse (BG) and the cross-border crossing point of the Friendship Bridge.

Through the eyes of a Giurgiu resident, the idea of local tourism for the Danube region may seem superficial. With a tiny number (6)1 of accommodation units in the municipality and knowing that most of those who come to visit the city are only in transit to or from Ruse or Bucharest and choose to stay in one of these cities, it is hard to believe in a plan promoting a regional tourist circuit at the local level.

On the one hand, Giurgiu's tourist potential is not being exploited due to the lack of the necessary infrastructure for such activities, but more importantly due to the limited leisure opportunities for the city's inhabitants themselves (a cinema that has been closed for decades and few, poor quality socio-cultural alternatives). This problem is a reality that all local actors (administration, private sector, citizens) are aware of in cities like Giurgiu or similar. In fact, there are many causes of this situation: political, economic, historical, socio-cultural and regional.

With the decline of industry and cross-border trade, the city's economy has undergone massive restructuring, and Giurgiu has significantly felt the effects of the transition economy. Socio-economic indicators point to a strong demographic and economic decline in Giurgiu over the last three decades.2 Over 29 years (1992-2021), the city's population has decreased by 14%, the natural increase is negative and the number of domiciled employees is continuously decreasing3. At the same time, Giurgiu County remains one of the regions with one of the highest rates4 of people at risk of poverty and social exclusion in Romania and the European Union.

The phenomenon of negative urban sprawl is not new, but in Eastern Europe it has been studied more closely over the last two decades. Specialized literature shows that most cities in socialist countries have been affected by urban shrinkage, with the "pole of urban decline" currently located in Eastern Europe. Negative urban development is the result of various transformation processes: deindustrialization, sub-urbanization, post-socialist transformations, migration, etc. The challenge posed by urban decline is its unintentional nature5, being essentially a consequence of political and economic decisions interfering with urban planning6.

In the case of Romania, the phenomenon of urban shrinkage has been critically analyzed and researched7, charted and addressed by professionals from an interdisciplinary perspective, through community and socio-spatial interventions. Urban decline has been deciphered and addressed in participatory ways in cities of different types and sizes - Anina, Reșița, Petrila, Turnu Măgurele, Băile Herculane, Brăila, Galați. Participatory tools and strategies such as tactical urbanism, active planning, community development, urban regeneration and socio-spatial analysis have been integrated into local urban regeneration solutions that have had measurable impact on communities and built spaces (the case of the Petrila mine). In declining cities, the repositioning of planning principles can start from activating the roles that citizens and the administration play in the direction that urban life can take in a given context. Sociological theories show that it is within the power of individuals and communities to create new structures, rules and values for a given system, be it urban in this case. Cities have always gone through a process of transformation from development to reinvention8. And this makes urban decline just one essential step in a process of transformation that can bring about these new social patterns.

On the other hand, the communities of shrinking cities are problematic and need community facilitation and educational animation (inert cultural sector) in order to be able to assume and regain their cultural, local, social and regional identity. Mistrust, lack of social cohesion, 50 years of socialism, socio-economic cleavages and inequalities coupled with serious economic problems of local administrations have contributed to a passive state of the community for which values such as built heritage, natural or intangible heritage, local cultural resources or local valorization initiatives are resources and concerns that are put on the back burner.

The physical decline of the city has also led to a social decline, which has affected the relationship of the inhabitants with Giurgiu and has sedimented the reluctance to a positive scenario for the future. The desire for change is present, but until the moment of empowerment and action, there is room for smaller but essential steps and an external impetus. The need for people to see the city through different eyes is more urgent than it has ever been. A fresh perspective, leading to a renewed sense of hope for Giurgiu, can set in motion the change long awaited for years.

Smârda - historic neighborhood brought to light

How do you open a dialogue with the inhabitants of a neighborhood on the historical value of the place where they spend their daily lives and turn the magnifying glass they themselves hold in their hands to see the invisible next to them? How do you convince the local authorities that there are values to promote, when the local narrative is that of a port city where the shipyard is no longer a local engine, the sugar factory is a ruin and has long since ceased production, the young have left for other lands for a better life, and the old and the people left in the city hover between passivism and disillusionment.

This game of perspective in a context of urban contraction is a suspense movie with an unknown ending. At the grass roots it's fascinating to seek to bring out local heritage through action research in a seemingly desolate landscape, but communities and people always take time to gain confidence in their own strengths.

If you try to reconnect with Giurgiu on a macro level, as a resident it can be overwhelming. Not because the city doesn't have heritage elements in which to rediscover the history, feeling and importance of the city, but rather because all this heritage is removed from the everyday reality of the residents. So you start to look closer to home at what heritage means as part of everyday life, in already familiar spaces where the idea of change doesn't seem so overwhelming, but where people still overlook the importance of place - in the neighborhood. This is how we ended up in Smârda.

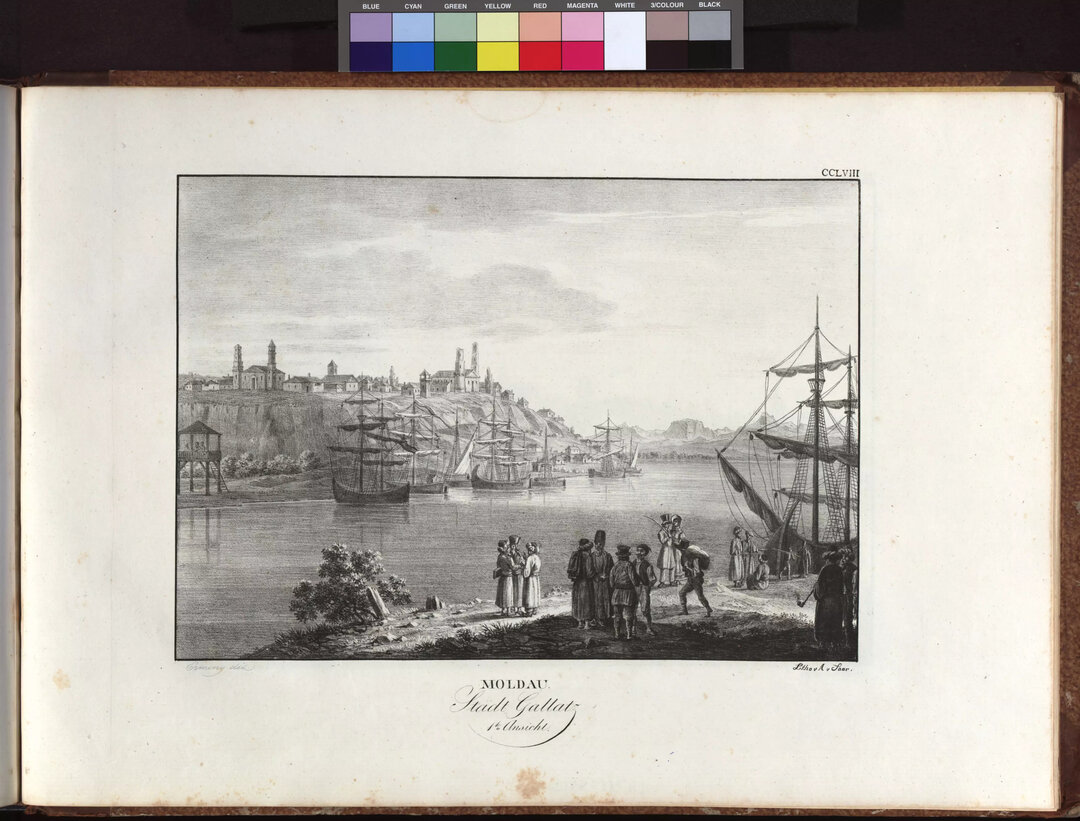

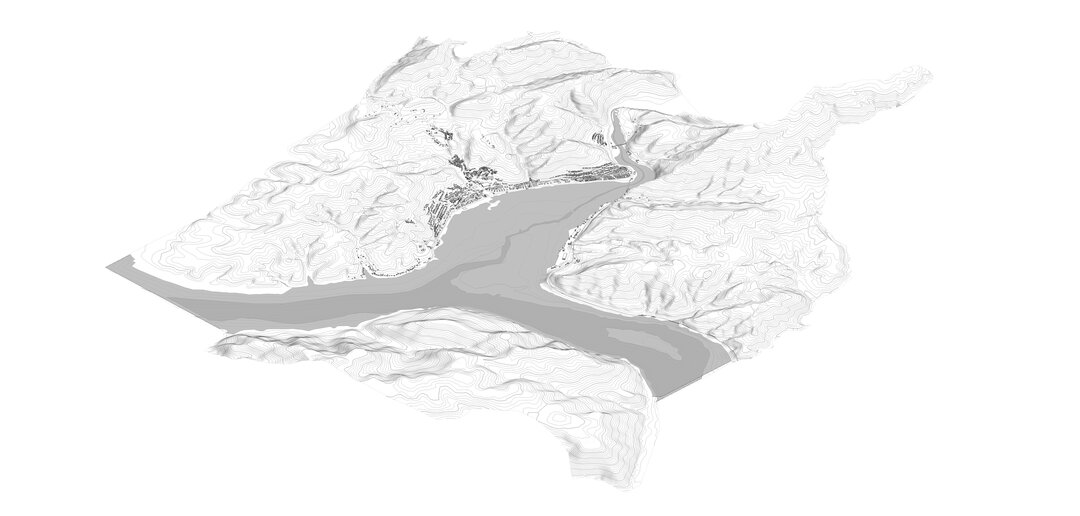

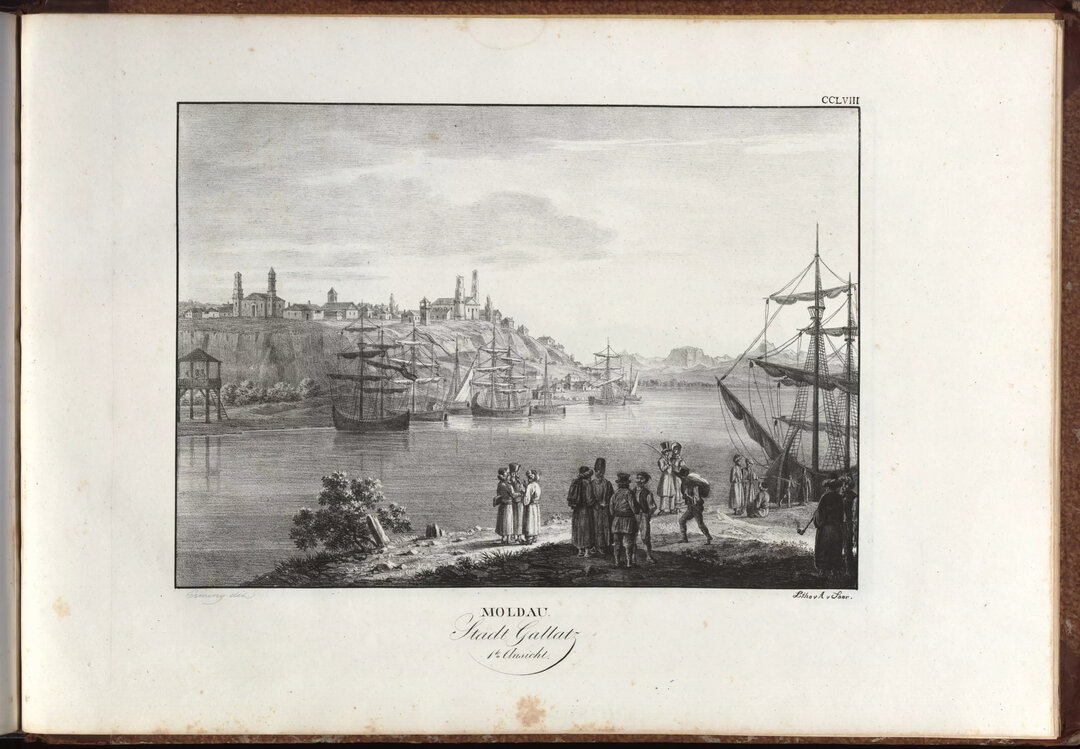

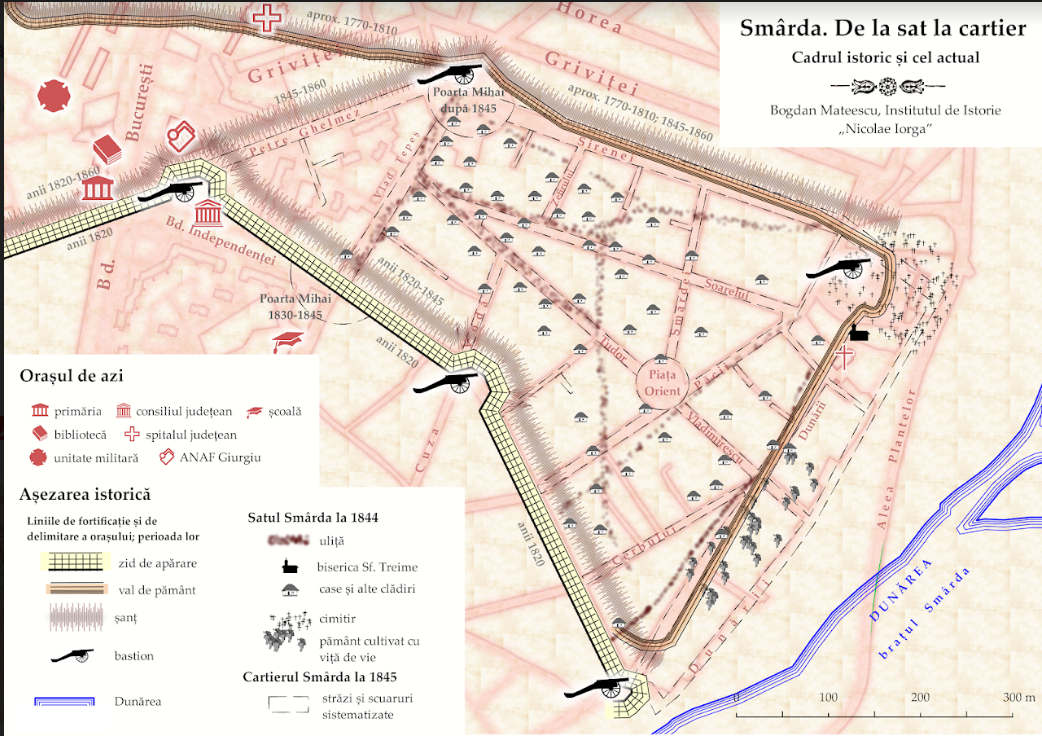

Smârda has been around since the region's Ottoman period and has gone through a series of unique changes from the 18th century to the present. From a village outside Giurgi defined by its relationship with the Danube, whose proximity gave it its name, from its significance as a swampy land to a neighborhood integrated into the city and systematized by engineer Gheorghe Foncescu in 1845, Smârda has taken an increasingly central place in the city's history over time. However, its historical value is not fully recognized. Smârda is one of the oldest neighborhoods of Giurgiului, with the street network preserved almost intact since the first systematization of the city. Although it is only 15 years newer than the rest of the historic city, Smârda is not considered part of the old city and is not classified as a historic center10. This makes unearthing the neighborhood's history all the more important as the memory of places of particular significance in the history of the neighborhood and its surroundings is being lost11.

Smârda became in 2022 a laboratory for experiments in community activation. A series of activities to promote the idea of heritage in Giurgiu and a pilot participatory street consultation session on canvassing local needs and problems brought us people and young people interested in discovering the city but reluctant to get actively involved. Smârda, in contrast, gave us the space to try a different approach. We took a neighborhood with an important but invisible heritage and gave residents a reason to believe in it. We gave them a chance to be proud to live in Smârda. A few months later, with the help of a working group of local historians, it turned out that the exercise of putting the neighborhood on the mental map of Giurgiului had sparked people's interest in getting involved in its future.

The history of the neighborhood and the mapping of its architectural and social heritage were included in the photographic exhibition "Smârda - Then and Now"12. The series of superimposed photographs from the present and from the neighborhood's public and private photographic archives were complemented by the Smârda story created by a group of local historians.13 In black and white and color, Smârda's heritage emerged to the light from the books, archives and forgotten areas where it was hidden. Residents were able to understand its value with an overview of the types of heritage from industrial (the Sugar Factory and its housing complex) to natural (the Plant Canal and the Old Beach) and historical (the Tabiei Wall, the Water Tower, the Church of the Holy Trinity) that can be found in Smârda.

Making the invisible visible helps to give direction, a new breath and can mobilize residents, from small to large, to get involved in celebrating and activating heritage in the short term. During the Danube Days Festival, an impressive number of local actors, from citizens to associations, public institutions and small businesses, showed their interest in supporting the neighborhood. Creative workshops in the courtyard of the city's last remaining borough, exhibitions of historical and environmental photography in the redeveloped Sugar Factory park or guided tours through the streets of Smârdei were just some of the activities organized to promote the tangible and intangible heritage of the district.

But from enjoying heritage to helping save it is a considerable distance and needs a solid foundation of hard work, dedication and respite. Such short-term community activations play an important role in strengthening a sense of change in a neighborhood, of imagination for a future built together with attention to local values. But turning this image into reality requires turning these and similar pockets of enthusiasm and other similar pockets of active civic engagement into recurring opportunities for action, with logistical, financial and strategic support that can enable them to grow.

La Bordei - the heritage and community element

During a research on the role of community activation in peripheral cities on the Danube, we discovered, in Giurgiu, a unique bordei in the regional landscape. The building is located in the urban fabric of the central part of the city and has a history closely linked to that of the Smârda neighborhood, of which it is part. If the theory of community development says that the improvement of a community generally starts from human resources, in the case of the bordei, the path is the other way around, from object/place to community in the way we have thought about the harnessing of its latent potential in the community organization we have developed during 2021 and 2022. Bordeiul is a type of semi-buried dwelling used since prehistoric times. In the eastern Danube region, people lived in the villages until the beginning of the 20th century. The reasons had to do with security, the materials used to build such a dwelling - the raw materials being readily available in nature, what today we would call sustainability - and the relatively constant temperature inside. In the lowland villages, in 1860, the highest percentage of rural dwellings was in Teleorman, 77.9%, while in Vlașca the percentage was 16.2%. In a statistic drawn up 50 years later, in 1912, the percentage of 'bordeie' in Vlașca had fallen to 1.3%. The Giurgiu Bordeiul was most probably built in the last decades of the 19th century. An official document from 1883 mentions a bordei in the Smârda district: "The bordei with its place in Giurgiu, Dunărei street, black color, composed of two rooms with their awning, dug in the ground (...)".

The Giurgiu Bordeiul, uniqueness, history, importance

For a simple, small-scale construction, the Giurgiu borough is of colossal importance. It is most probably the only bordei left in situ; there are still peasant bordei at the Village Museum in Bucharest, but they have been displaced from their original areas.

The bordeiul is a curiosity in itself, its existence is a vivid illustration of the history of the Smârda neighborhood, which was a village during the Ottoman administration of the city. After the departure of the Turks, the Smârda district was integrated into the city and a century later it was mentioned with the "black color", together with the other districts or slums colored on the city map in green, red, blue and yellow.

The communist administration of Giurgiului in the 1950s declared the borough a historical monument, probably as an illustration of the living conditions of the "working class" during the times of "bourgeois-landlord" oppression, yet it was permanently inhabited until the early 2000s. People in the neighborhood still remember Auntie Maria drying pumpkins on the roof made of red Tuscan pottery and receiving visits from pioneers who came with the class to see the bordello.

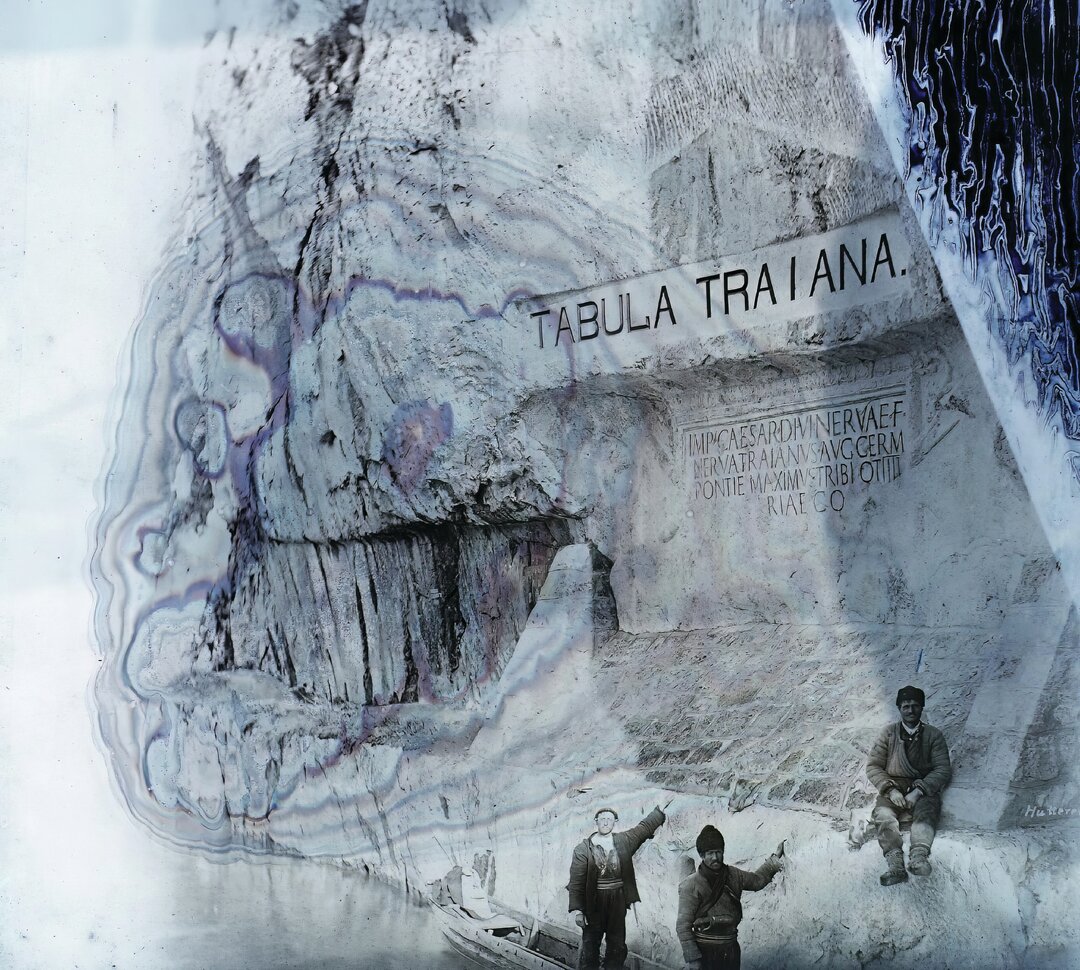

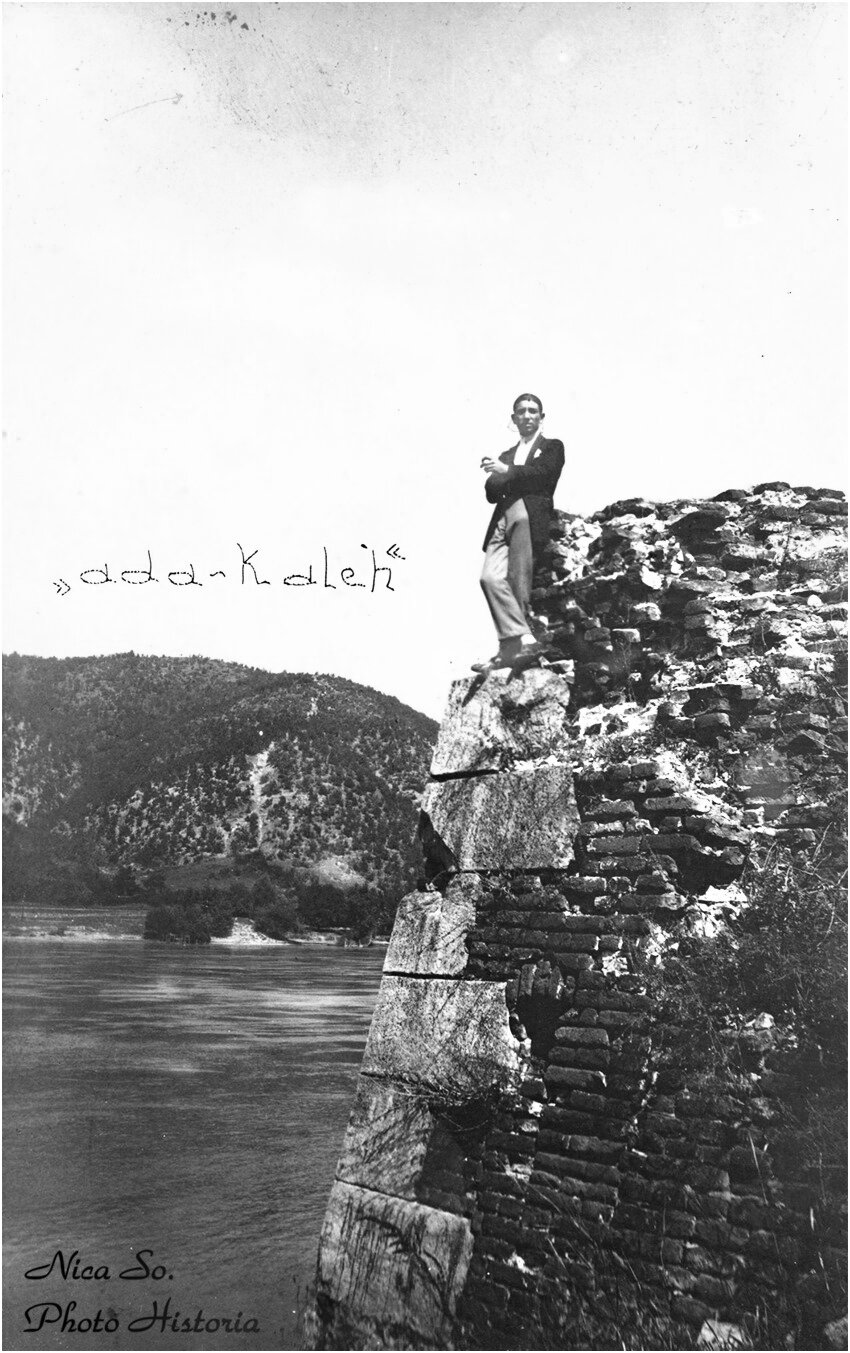

However, the biggest addition that the borda brings to the history of the town and to the revitalization of the Smârda area is the subtle links it has with the other monuments that remain from the Ottoman period of Giurgiului: the clock tower (fire gazebo), the Tabia (fortification in the immediate vicinity of the borda), the fortress on the island (defensive fortress), the Schitul Sf. Nicolae (geamia Bairaclî), the borough taking part in this picture as a way of living commonly found in the Danube plains.

The stake of local identity - the key to change in a shrinking city

The borough has gathered around it a community of people interested in preserving it as a historical object and transforming it into a community center in the near future. While civic communities often coalesce around a burning issue, the community of "La Bordei" is an atypical case for community organizing, with the stakes being to improve the building and return it to community use through private efforts and funding. While such situations signal a transformation of perception in a depressed urban context, such initiatives cannot sustain themselves and the winning route of such a scenario can be difficult to say the least. Its private property status on the one hand helps it to preserve it as a historical testimony but on the other hand hinders it in the area of public funding for the purpose of its more rapid development, securitization and then rehabilitation.

The steps we've taken with the La Bordei community have gone in tandem in terms of the needs of the space and the community that cares for it.

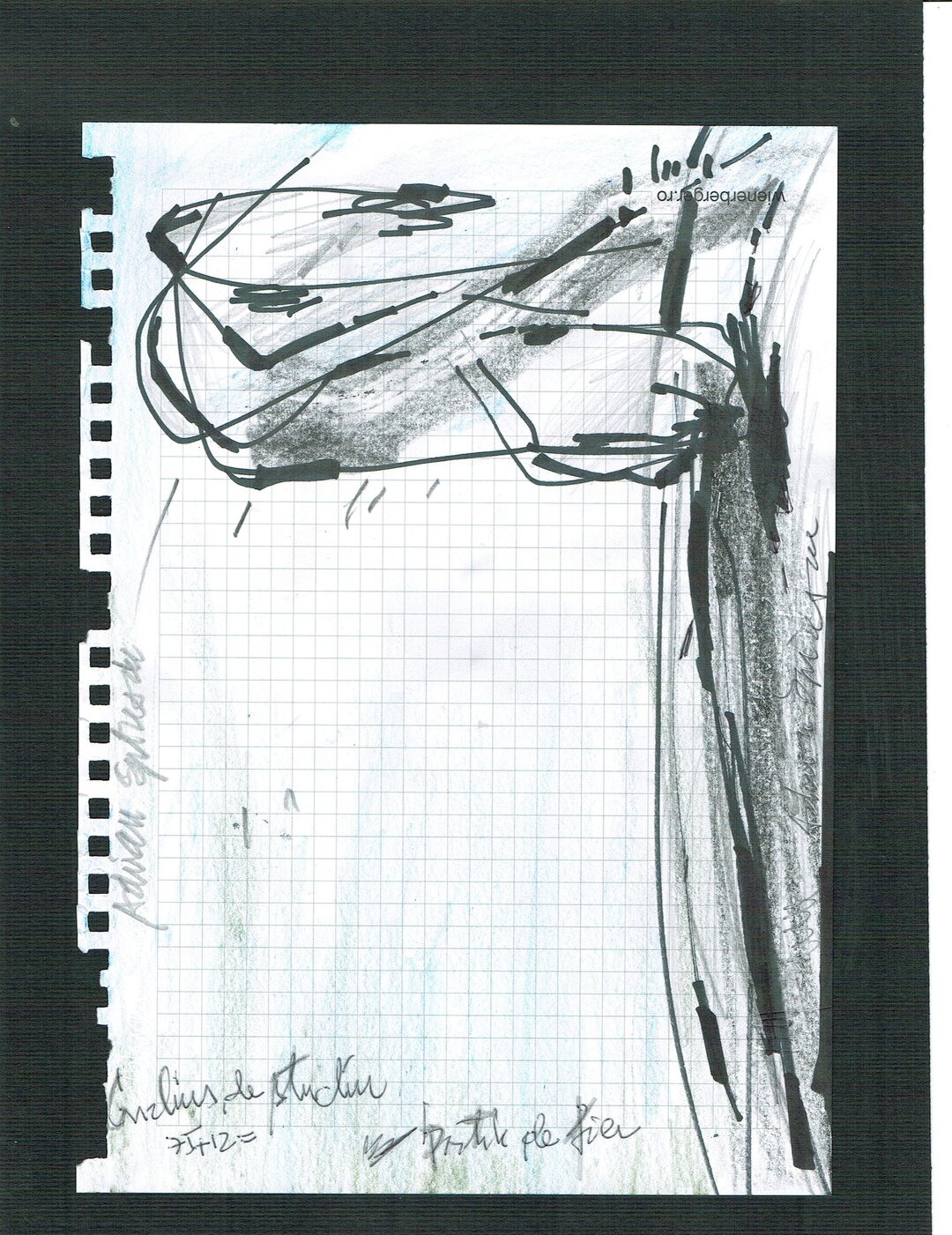

Cleaning the courtyard together, the call for involvement by organizing local workshops and events in the courtyard of the Bordei, the geotechnical and topographical surveys, the fundraising campaign, all were designed as steps of good community organizing to attract energies and funds to save a historic building. The local administration and local stakeholders helped to create a local event by partnering in the Danube Days Festival 2022 - a festival that, although financed by European funds, at least in terms of image, highlighted the untapped local potential of the historic Smârda district.

The year of events about and in the historic Smârda district have opened the dialogue on the unvalued heritage, but the road to turning the borde into a community center is only just beginning. The Bordeiul has the future that the community is building for it, it will only survive with civic involvement and perhaps tell its story further.

Conclusions

Civic and community activation can play a major role for communities in shrinking urban cities, but this tool is not sufficient for active intervention to mitigate the impact that urban decline can have on the quality of urban life. The development of a city is also very much linked to community perceptions and aspirations, something that is built over time and with the help of community facilitation and civic activators. People are the first who can help to open up the city, to turn it, as I was saying, to face the Danube by embracing its heritage. But it is also the people who need support structures to carry the work, commitment and enthusiasm forward in the long term, in an unfavorable context. An integrated understanding of the conduct of a city in decline is necessary and indispensable for a rethinking of planning based on the principle of adapting the tools to the local/on-the-ground situation15.

Dedicated literature points to a key ingredient in successful strategic planning for a shrinking city as a process involving citizens, the public sector and civil society. Especially in peripheral areas, it is recommended that, from the outset, ideas about local development should be mapped out together with the people. The city has the option to cede total control and share it with neighborhoods and communities, safe in the knowledge and belief that the locals know these areas best and can come to the discussion with ideas and plans from their expertise/perspective as residents. In this context of a social mechanism undergoing profound changes, can community be rebuilt through collaboration? How does one collaboratively define a problem? And last but not least, how can and should working with communities become a usual part of the process of developing a local strategy? These are questions to which Romanian cities are still searching for answers.

NOTES

1 http://statistici.insse.ro:8077/tempo-online/#/pages/tables/insse-table

2 http://statistici.insse.ro:8077/tempo-online/#/pages/tables/insse-table

3 Ibid.

4 Local Community Development Strategy Giurgiu 2015. Community-led local development, available at https://qvorum.ro/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Strategie_dezv_locala_Giurgiu.pdf https://qvorum.ro/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Strategie_dezv_locala_Giurgiu.pdf

5 Oswalt, 2006.

6 Annegret Haase, Katrin Grossman, Dieter Rink, Shrinking cities in postsocialist Europe.

7 Păun-Constantinescu 2019, Shrinking Cities in Romania Vol I&II.

8 Ghenciulescu, 2019, 317.

9 Mateescu. B, Institutul de istorie N. Iorga. Historical research on the urban and demographic evolution of Smârda neighborhood, for DANUrB+.

10 Plan urbanistic general. Municipiul Giurgiu. 3. Zonificări funcționale, căi de comunicație și restricții tehnice, scala 1:10000, planșa 3, realizat de S.C. Mina-M. Com. S.R.L., reference no. J40/20209/1992.

11 Mateescu B., Smârda: a rediscovered history (2021).

12 Gheorghe C., COCON Studio.

13 Teohari Antonescu History Museum, Mateescu B., xx.

14 Community activation photo concept by Gheorghe Costin/Cocon Studio for DANUrB+ action research.

15 Stan. A, 2019, 172.

16 The DANUrB project is part of the European INTERREG-Danube Transnational Programme (www.interreg-danube.eu/) and aims to reactivate cultural heritage and underutilized resources in settlements in a state of socio-cultural, physical, economic and demographic contraction in the peripheral or border regions of the Danube. The main objective is to create new opportunities for the attractiveness of Danube cities and regions.

-topaz-denoise-enhance-sharpen--15883-m.jpg)

--15895-xl.jpg)

--15896-xl.jpg)

--15897-xl.jpg)