Danube Urban Front

© Anca Galiceanu

Workshop - year 5

In Claudio Magris's novel1, the Danube no longer has physical urban banks, banks from which to start today's stories; it floods the surrounding land as far as Bucharest, Adamclisi, Histria, binding it in a perpetual myth. Huge dead cities beside the river drown out the noise of today's living cities with the noise of their myths. The latter are as silent as the natural landscape that accompanies the Danube on the Romanian side. Over the last 70 years they have been crushed by a flowing water perceived as an insurmountable limit2and the rest of the country towards which they have been forced to turn their gaze.

While political motives may be a key to this reading in Romania, the economics of water-oriented cities has played a decisive role in separating the city from the water throughout the world since the 19th century. This separation depends on a multitude of reasons: different ways of planning (port planning on the one hand and city planning on the other), varying administrative responsibilities, incompatibility between port and urban activities, and growing needs for efficiency, safety and flexibility in ports3. Mutations due to the increasing scale of trade, ship size and mechanization of operations have transformed ports around the world into areas closed to the public and exclusively dedicated to economic activities.

The rediscovery of many European cities' relationship with water is a relatively recent event. As recently as the 1990s, Barcelona had a waterfront dominated by industrial platforms. The organization of the 1992 Olympic Games was a turning point in the city's development, which in just a few years has become a benchmark among European cities in terms of quality of life and public space. At the same time, in cities such as London, Rotterdam, Paris, Copenhagen, etc., major urban transformation and restructuring operations have been carried out along the banks of the rivers, towards the waters towards which these cities open out. The rediscovery of openness to the water, now seen not as a limit but as a potential connection with the world, has already begun to happen in Romanian cities. But slowly, very slowly.

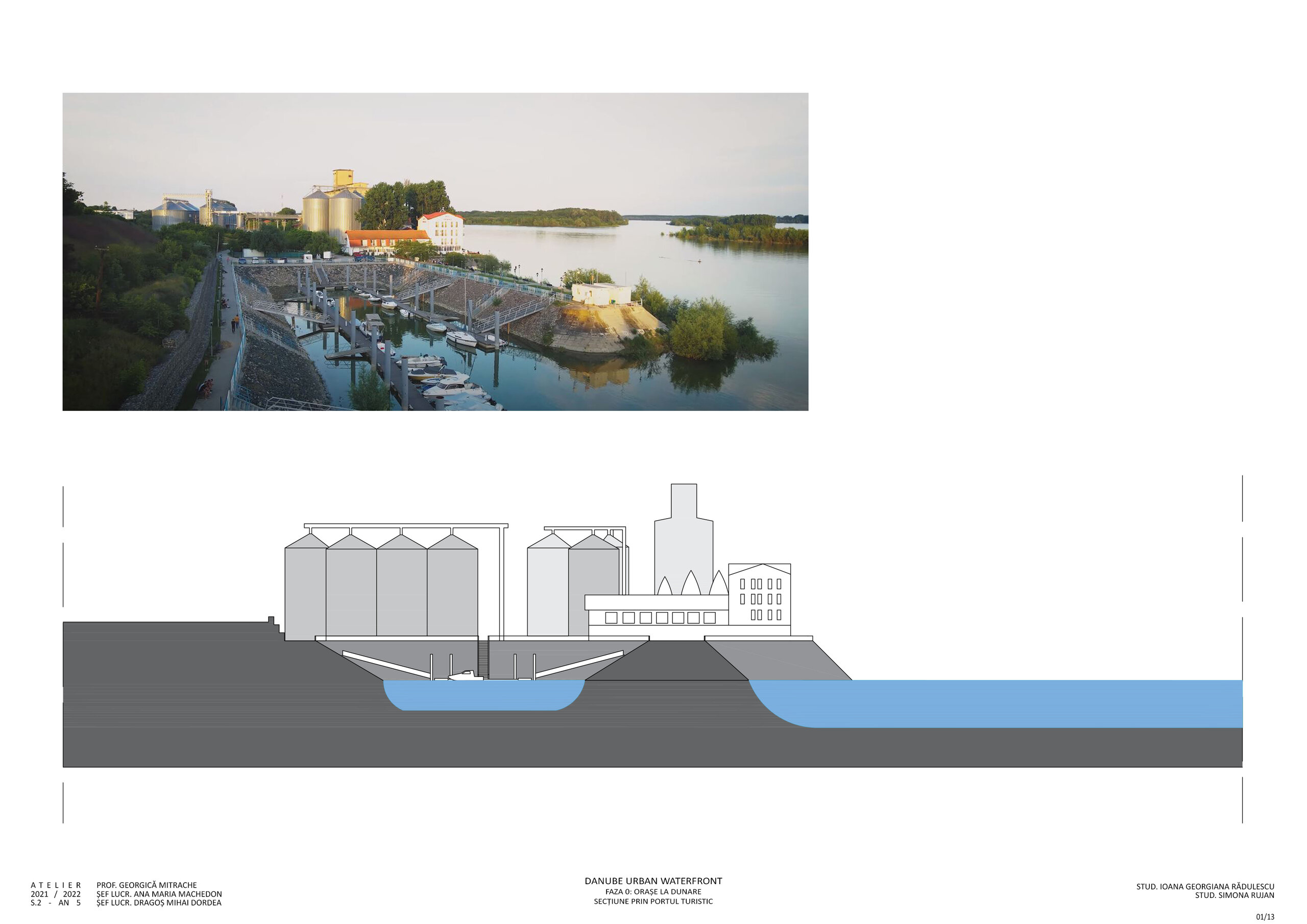

In the case of cities with an opening to the Danube, the situations are very different from case to case. There are cities completely cut off from the water by vast port infrastructures with economic activity still functional (Giurgiu), or cities where industrial activity is in decline or has been abandoned. There are cities where port areas do not overlap public waterfront areas and where the city has a direct opening to the river (Orșova, Brăila, Galați). Sometimes, this direct opening is not to the Danube, but to canals, marsh areas or islands and wooded sandbanks with natural banks (Corabia). Some towns, although having direct access to the river, ignore it completely, turning their backyards and gardens towards the water (Fetești). At other times, the towns are located on high cliffs with the possibility of opening onto the water, with industrial zones or harbors in various stages of use/abandonment at the base of the cliffs (Măcin, Calafat). Due to industrial development at the beginning of the 20th century, some towns are separated from the Danube by railroad infrastructures (Drobeta-Turnu Severin, Corabia).

While industrial and agricultural port activities will be technologically transformed to adapt to new requirements, waterfront areas will be enriched by tertiary, service or residential activities. In Central and Western Europe, the reconnection of cities (through the themes of civitas) to rivers has been a recurrent theme, and the waterfront one of the main architectural and urban themes. Talking of the Danube, for Vienna or Linz it is an urban river running through the city and offering countless spaces for promenades. Further west, crossing from the Danube into the Main and then the Rhine, cities such as Frankfurt, Cologne or Rotterdam are regenerating former industrial areas into new waterfront neighborhoods4.

In his book Aesthetics of the European City - Shapes andImages5, the Italian researcher Marco Romano identifies a veritable syntax created between the city's public and private spaces and buildings. Our social life has meaning only insofar as we belong physically to the physical form of the city and spiritually to its moralform6. Starting from the principles of liberty and equality, the defining principles of European democracy, the physical, formal definition of the community, its strength in competition with other urban entities, is through its dedicated buildings and civic spaces. Due to the vicissitudes of history in Romania, civic spaces (of the citizens, i.e. of those who voluntarily belong to and constitute the respective city, the respective town) are often seen as the actions of forces that do not depend on the local community except possibly to a limited extent.

Increasingly, however, local communities are realizing that shared, public, civic spaces (streets, parks, alleyways, monumental streets, promenades, bridges, fountains) and/or civic, public buildings (town halls, churches, museums, schools, libraries, squares, hospitals, stadiums, theatres), together with private, public spaces (restaurants, bars, shops, hotels), can, through their interrelationships, create harmonious or, on the contrary, discordant and unpleasant places. It is just that new investments sometimes do not take into account the location within an urban spatial structure, often referring only to the immediate availability of land. Cities must be developed by understanding and enhancing their own pre-existing structure of public spaces and buildings. How do these collective themes come together, relate to each other within the city, should be the first question for harmonious future development? And, of course, in the case of port cities, the first question should be: how do public spaces and buildings relate to the river, to the Danube?

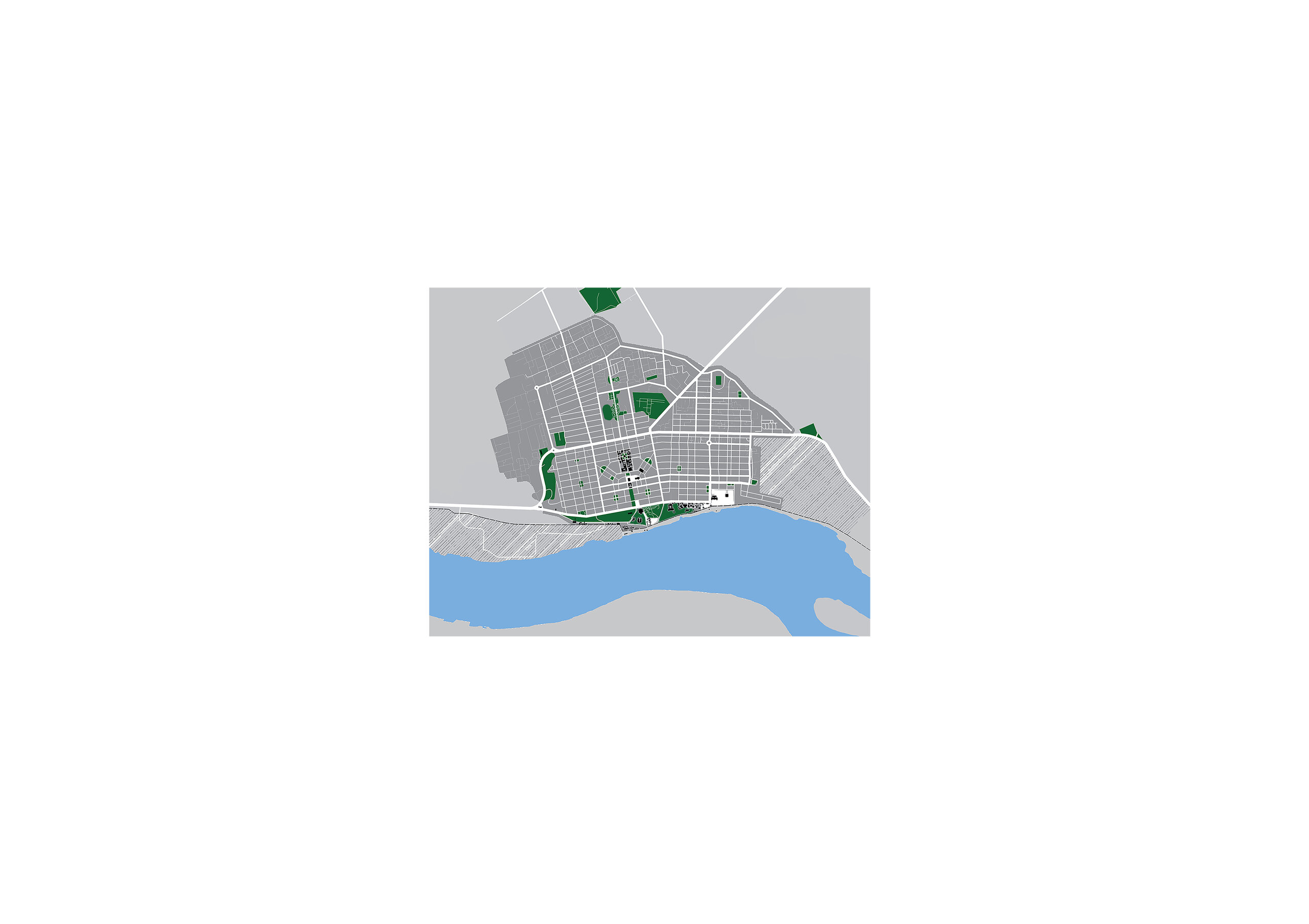

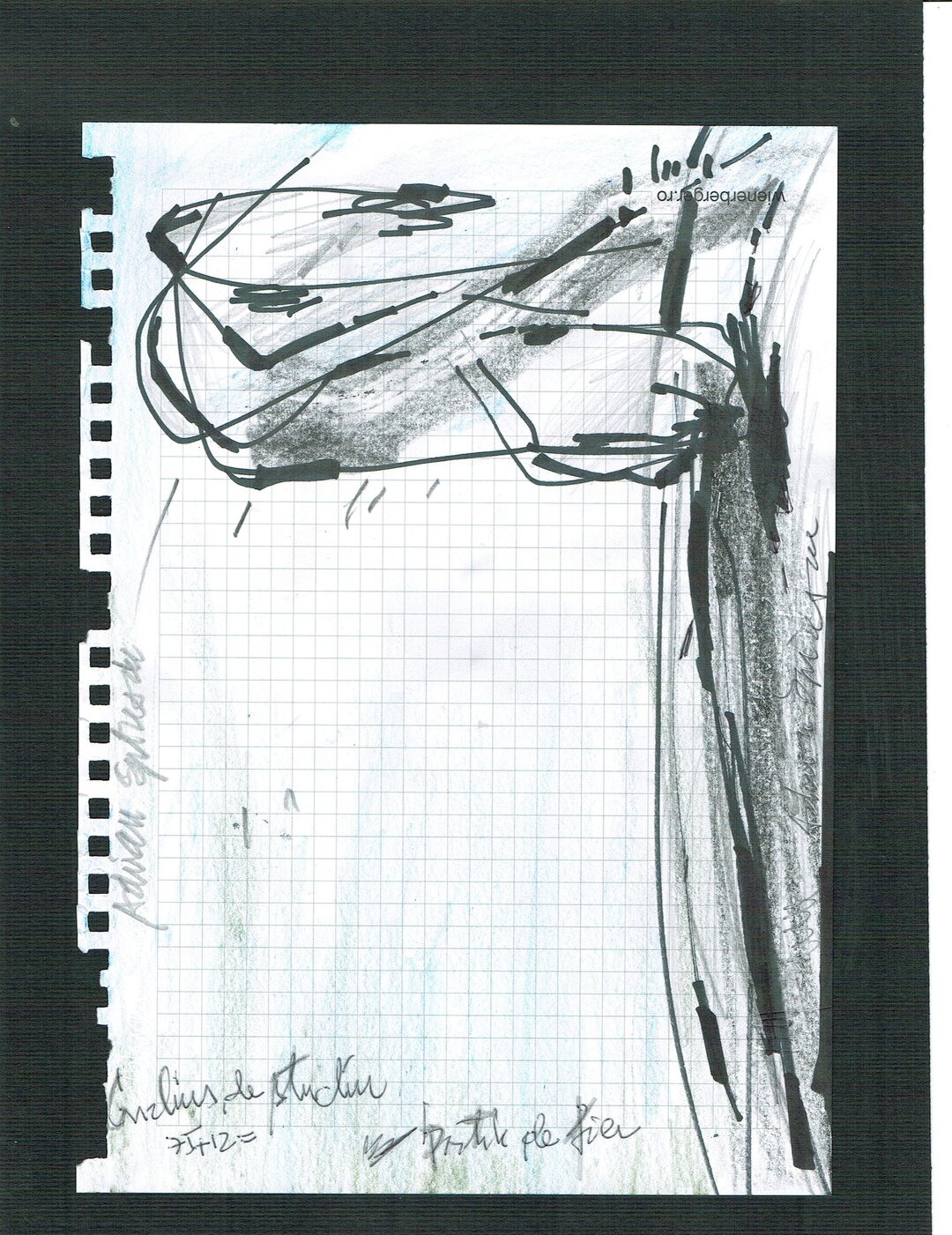

Together with the students of the 5th year workshop, we graphically analyzed the location of buildings and public spaces based on the method described by Marco Romano for 15 cities on the Danube in Romania. Highlighting urban voids in white and public buildings in black against a dark gray background, the plans are easy to read and invite you to read and travel. For each city I found a sentence describing my observations during the workshop.

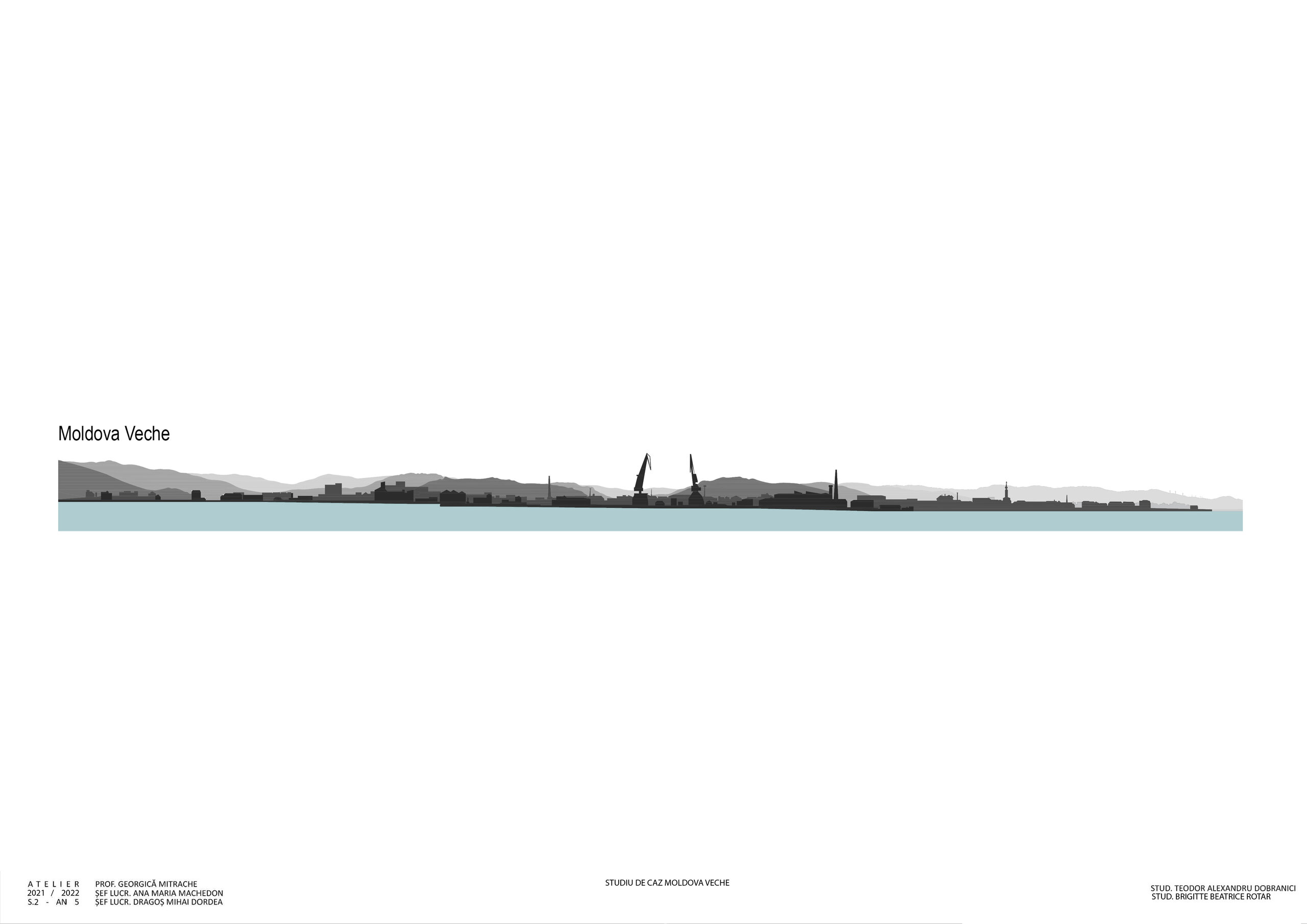

Old Moldova

The harbor is central; it separates the fabric of the old town that leaves only a few places of access to the Danube, from the 20th century expansion that opens up with wide green spaces towards the river.

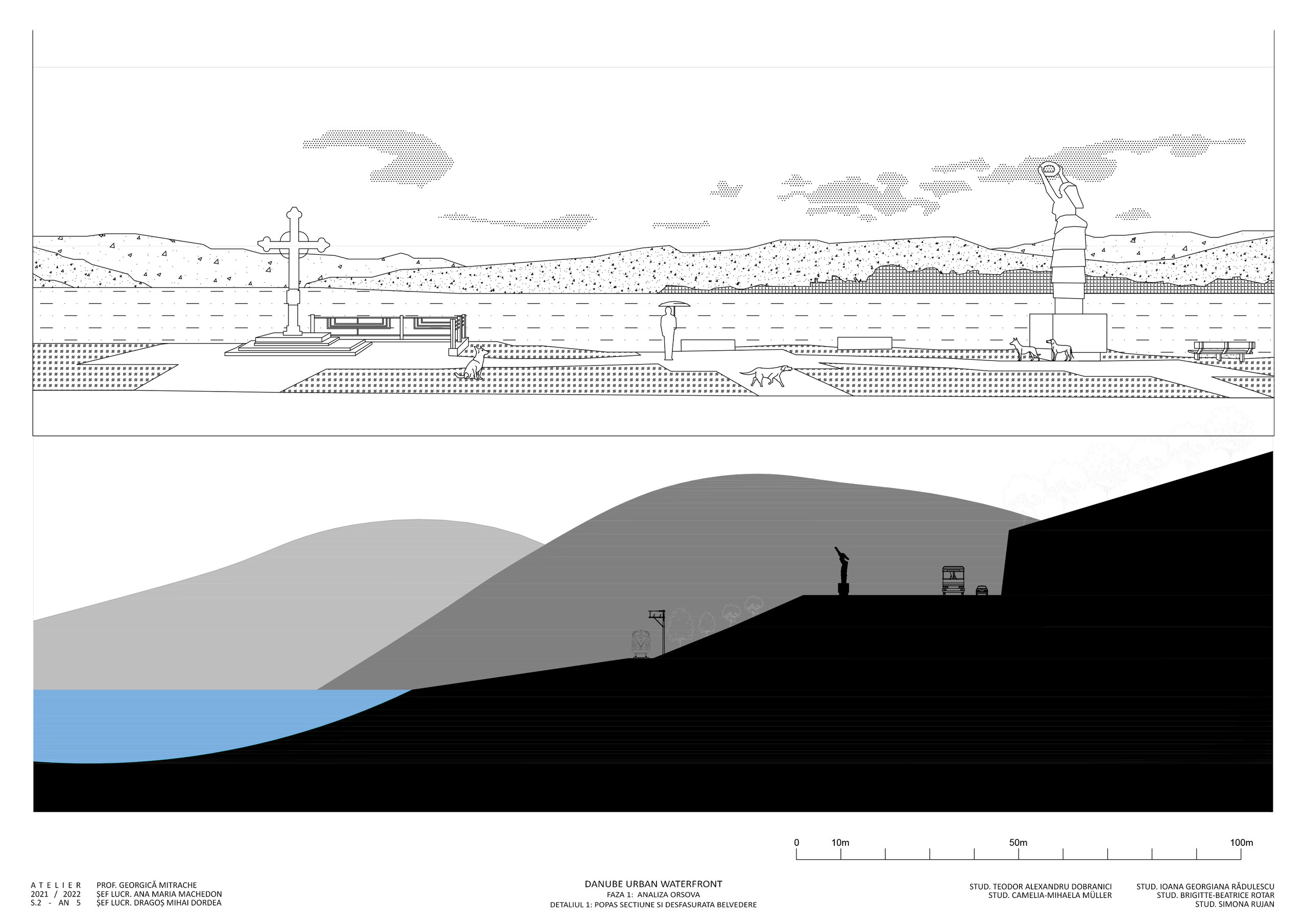

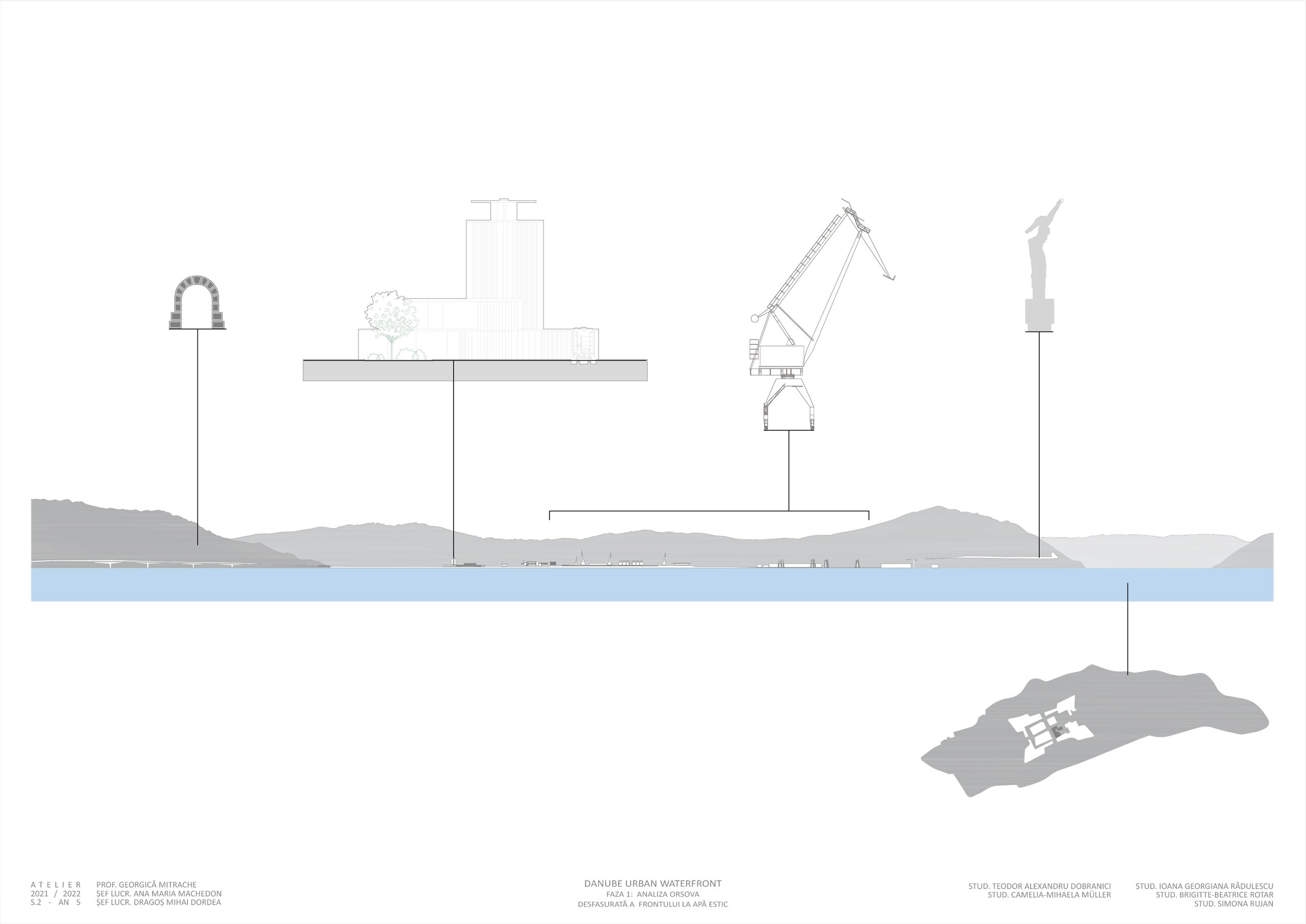

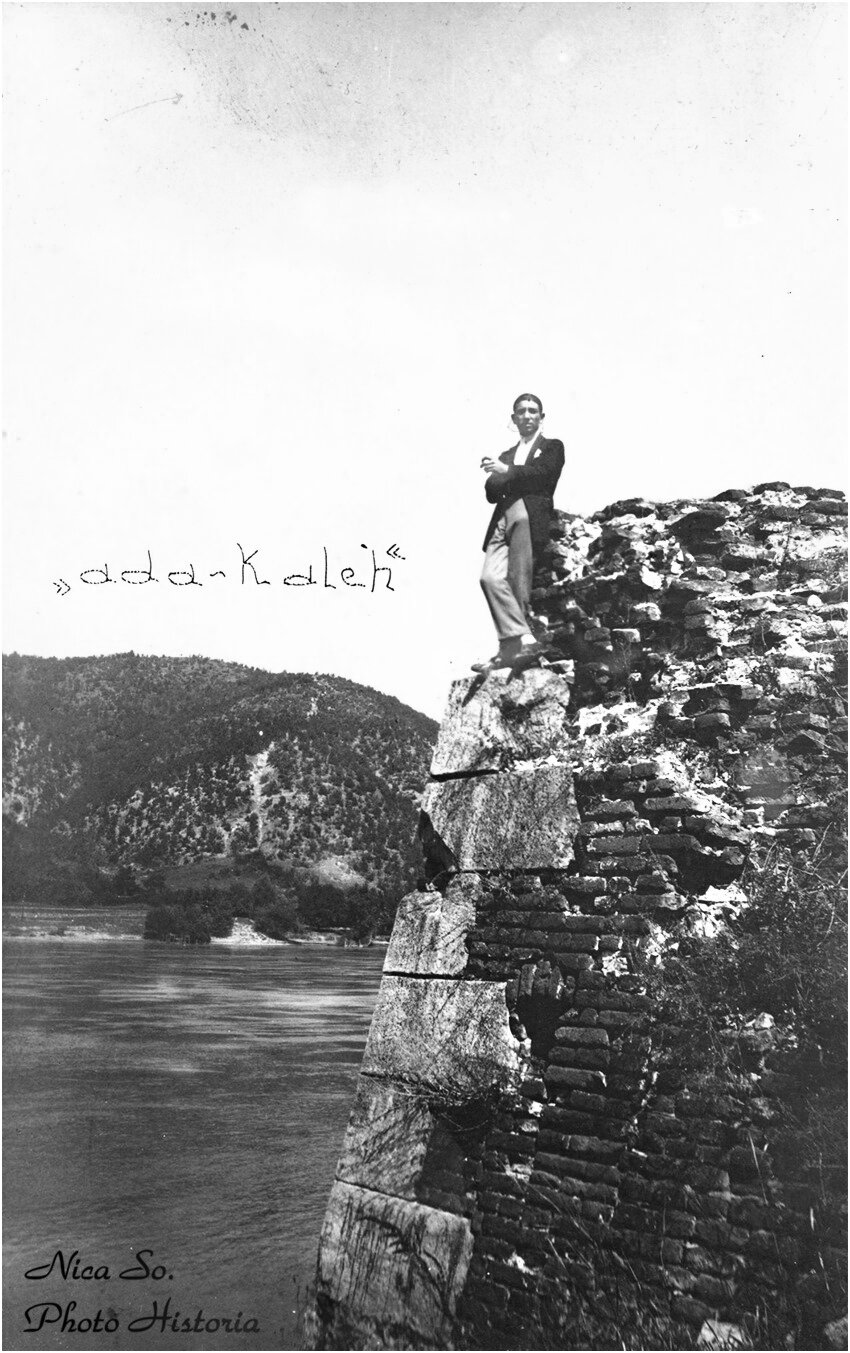

Orșova

The recent city would have all the attributes to become one of the most beautiful cities on the Danube, if history were left to contribute to the collective memory with the scents of roses and coffee lost under the waters of the new bay of Cerna.

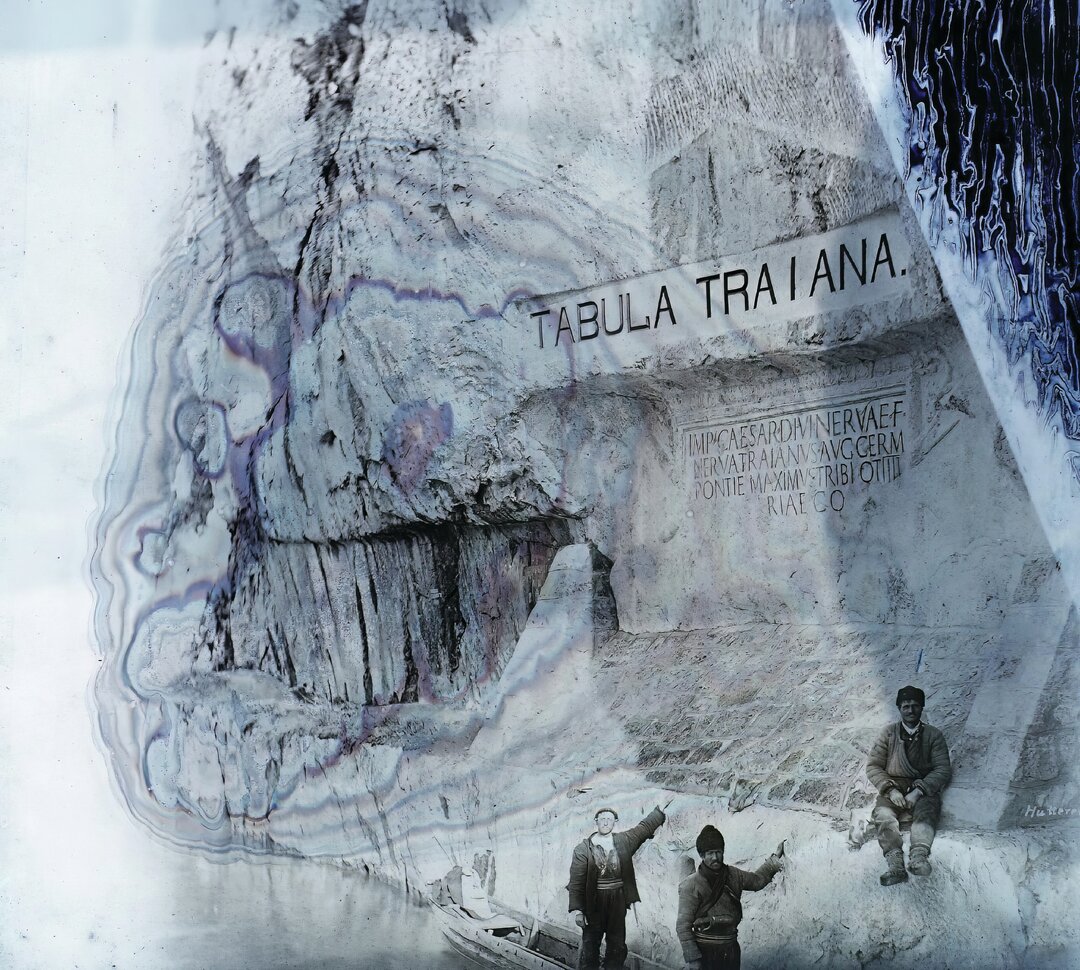

Drobeta-Turnu Severin

The urbanity of the place is emphasized to the limit of pleonasm by the three-word name; at least three spaces opening onto the Danube could be joined by public promenades to configure a consistent waterfront.

Calafat

Overgrown with almost wild vegetation, the city's seafront becomes an opportunity for a break between the shore and the city, blocking spectacular views of the water and the Calafat-Vidin bridge.

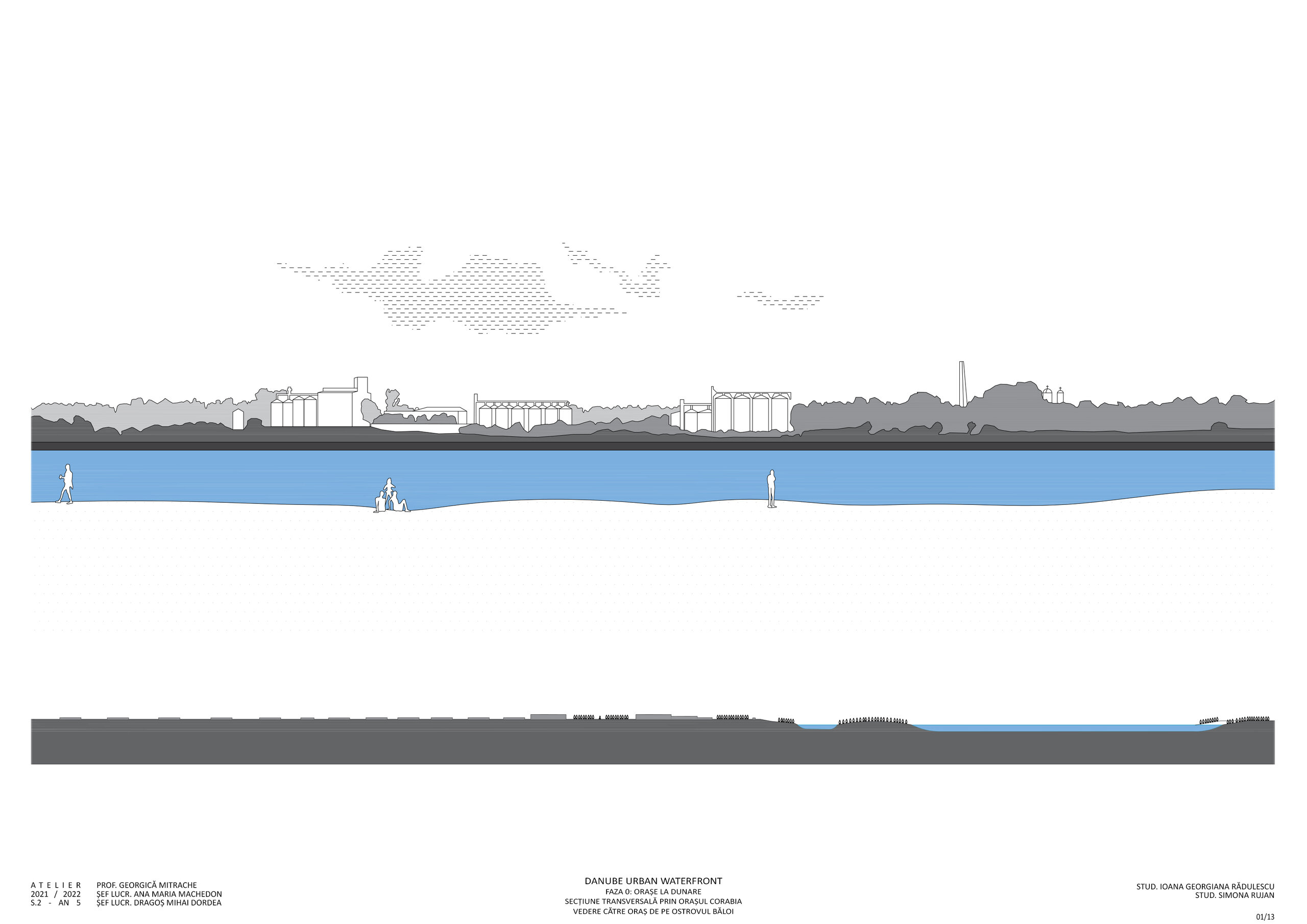

Corabia

Although clustered in a system of rectangular parks and squares facing the water, the railway and railway station separate the city's public spaces from the water.

Giurgiu

The old fortress of Giurgiu, embezzled for the construction of the 19th century city, partly buried under dykes built to drain the waterfront for industrial purposes since the Stalinist period, is awaiting a vast regeneration of the waterfront spaces.

Călărași

An elbow formed by an arm of the Danube beside which parks, beaches and public buildings are squeezed into a very small opening in relation to the rest of the city, shows the immense potential of spaces that can continue, east - towards Modelu - or west, as vast parks of protected areas in relation to a long unused industrial canal.

Fetești

A city of two cities - one old and one new, both created and separated at the same time by infrastructure - railroad and highway bridges.

Cernavodă

One of the oldest and most complex of the settlements along the Danube opens through a series of fragmented - historical - spaces to the Danube-Black Sea Canal.

Hârșova

The town has still preserved a compact character, typical of the former fortress whose walls are still part of the urban landscape; the spaces towards the water are ready for recovery and careful regeneration of a certain historical and natural heritage.

Măcin

The potential offered by the proximity of the water and the archaeological and landscape heritage given by the high site of the former Arrubium fortress is negated by the neglect and underdevelopment of the waterfront area.

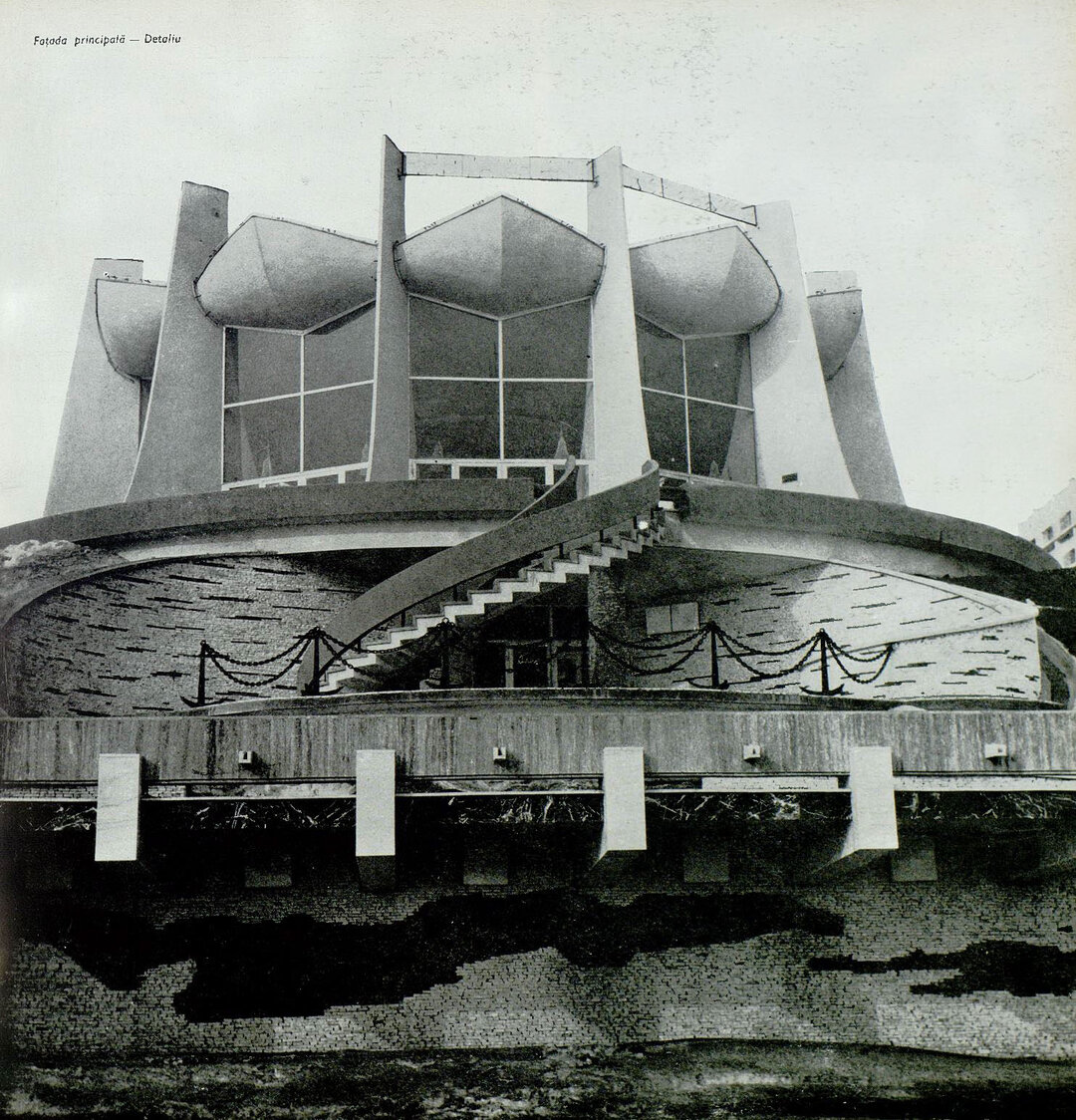

Brăila

The continuation to the north of the waterfront and the regeneration of the former warehouse areas which are today in a state of partial abandonment, already proposed in the new PUG, would revive one of the most beautiful cities in the Danube.

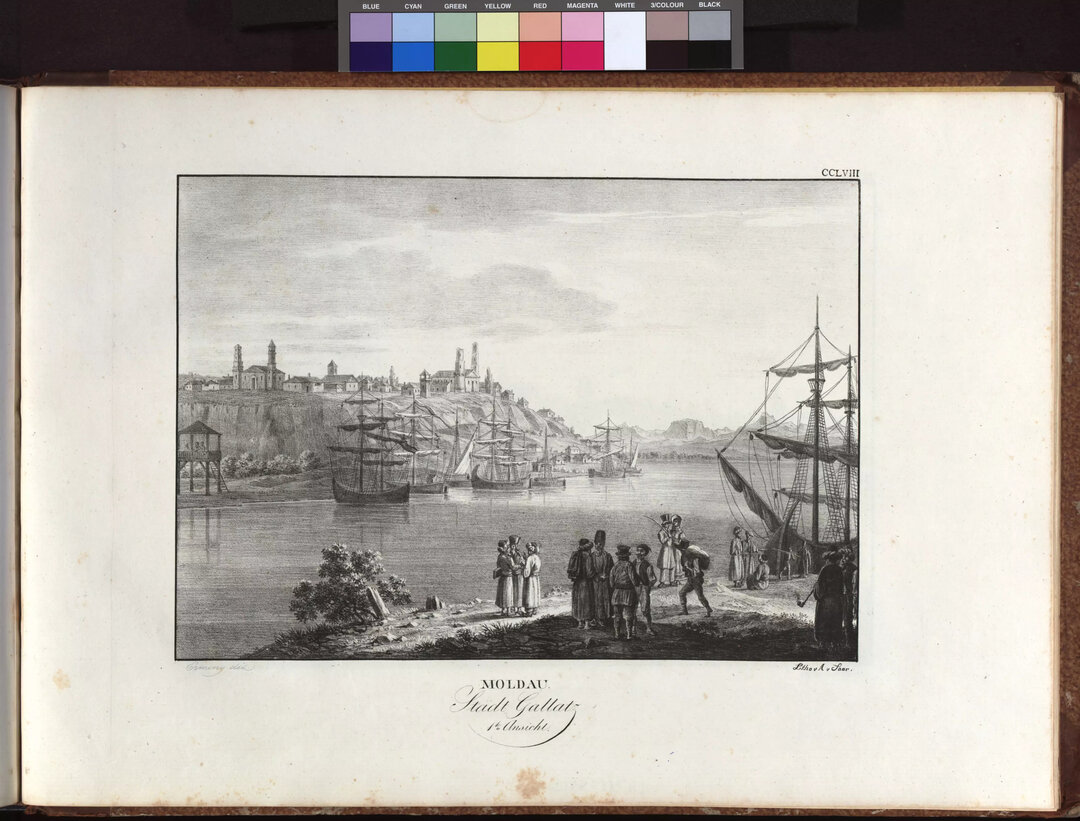

Galati

Waterfront areas, former floodplains turned harbor and huge depots delimit a dynamic waterfront in the process of redevelopment of the largest city on the Danube in Romania.

Tulcea

Wrapped around a meander of the Sfântu Gheorghe Arm, the waterfront starts to the west with Lake Ciuperca (or further on with Lake Câșla and that lesser known part of the deltaic territory) and, passing through a piece of cliff of reduced dimensions in relation to the city, climbs the hill with the appearance of a tumulus on which the main monuments of the city are located, being also the location of the ancient fortress Aegysus.

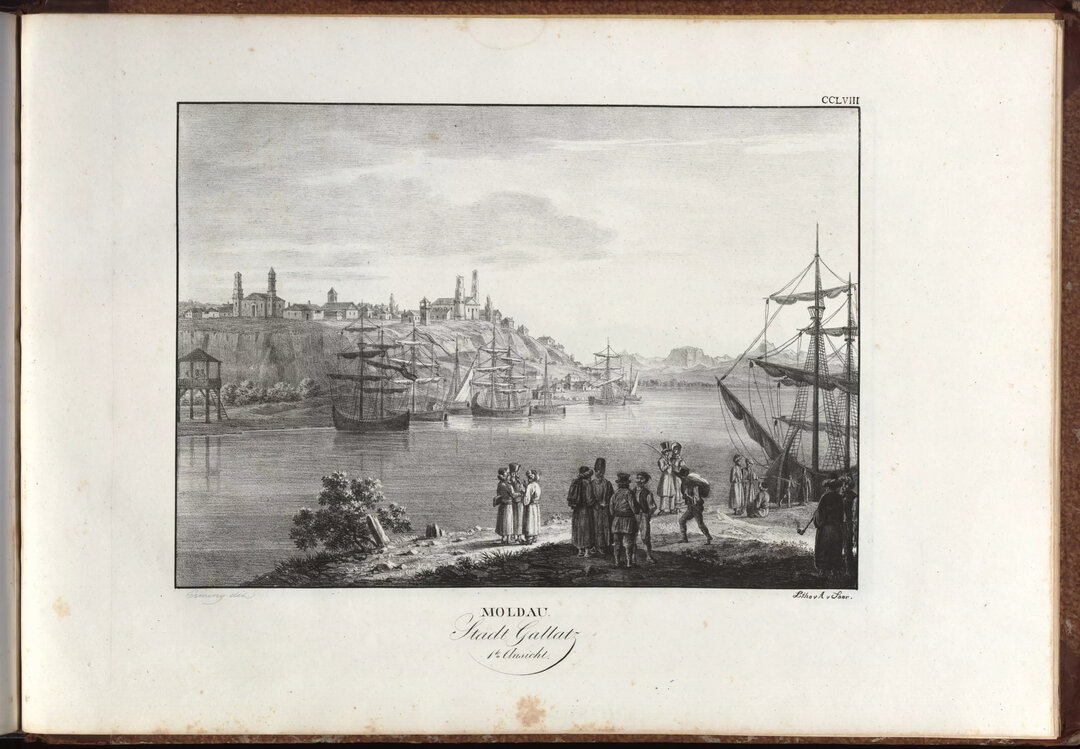

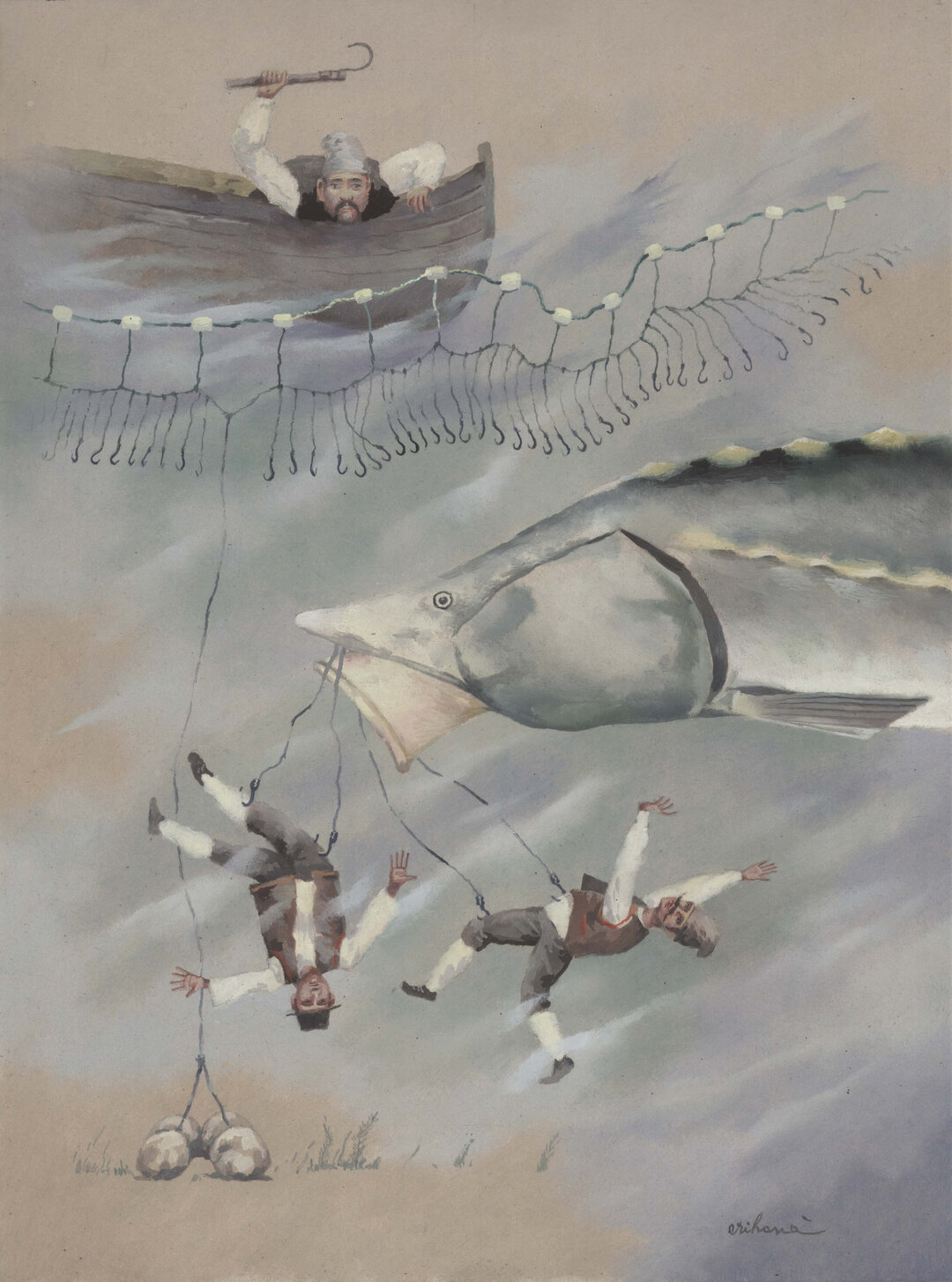

Sulina

The sturgeon-shaped town through whose mouth the Danube flows into the Black Sea has a very complex, multilayered waterfront that is felt deep in the fabric on at least three successive streets; the buildings that attest to its history, with the end of a prolonged transition after the 1990s, will become the main resource for regeneration and repopulation.

NOTES

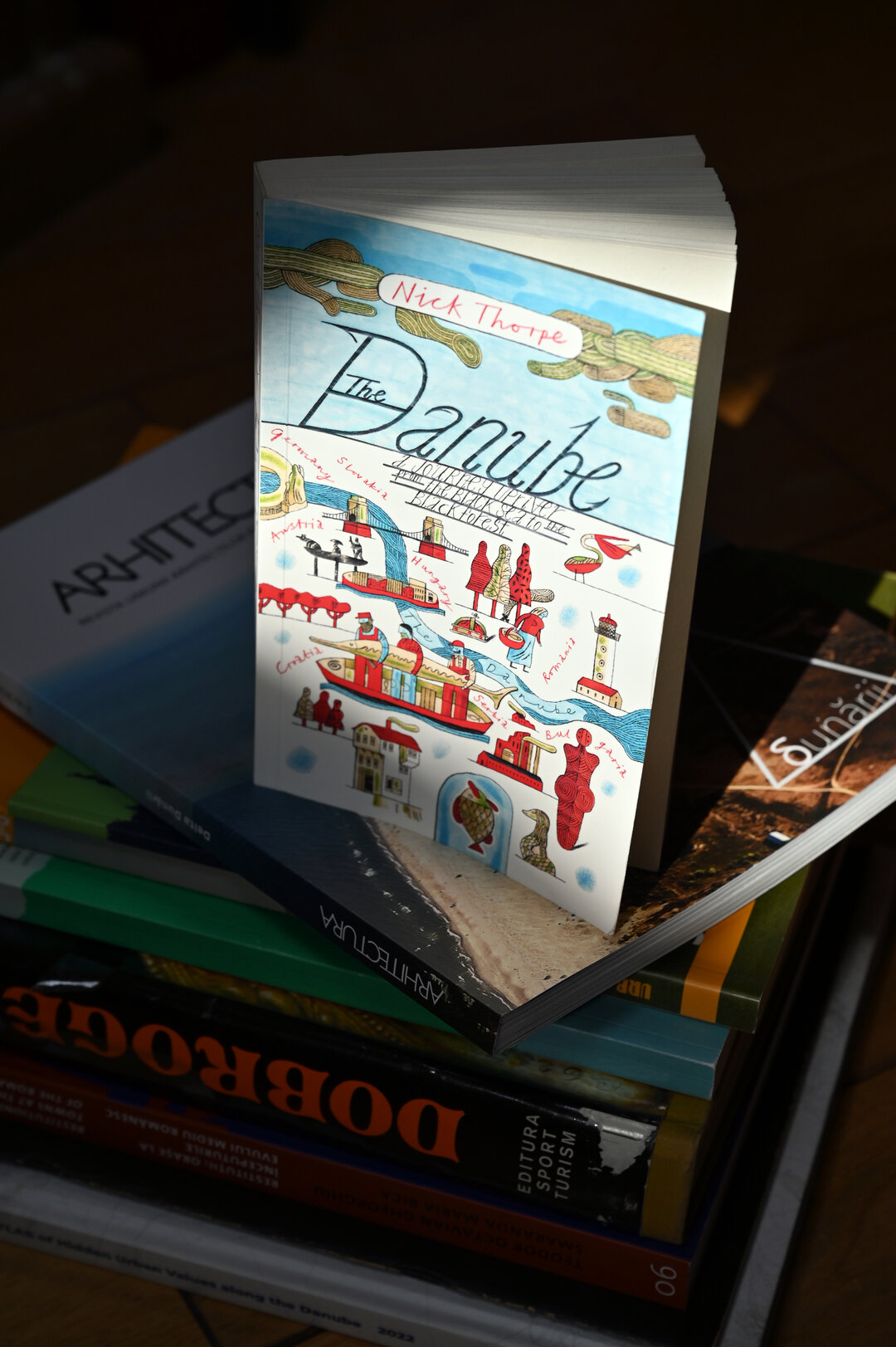

1 Magris, Claudio, Danubio, Garzanti, Milan, 2019.

2 In the case of the totalitarian communist regime, the Danube or the Black Sea were potential places to flee the country, hence the type of hard border, where one could not look in the direction of. The war in the former Yugoslavia, the embargo continued this idea of a hard boundary.

3 Rosario Pavia, Matteo di Venosa, Waterfront - from conflict to integration, LISt Lab Laboratorio Internazionale Editoriale, 2012.

4 The Offenbach district in Frankfurt, Rheinauhafen in Cologne or Kop van Zuid in Rotterdam are just a few examples of urban regeneration of former industrial areas into new neighborhoods along the water. They fit into the urban fabric and connect with the pre-existing waterfront spaces, contributing to an increased quality of life by making use of local natural resources - in this case the water of the river running through them.

5 Marco Romano, L'estetica della città europea - Forme e immagini, Einaudi, Torino, 1993-2005.

6 Ibid, p. 9.

-topaz-denoise-enhance-sharpen--15883-m.jpg)