The fisherman hunter

between prejudice and memory

The love of fishing

It is ingrained in the souls of the riverside dwellers by inheritance, they did not choose to be fishermen, they were born that way! The fisherman is a hard-working individualist par excellence, with a face streaked by the sun and the wind, his hands cracked by work and the cold, he practises an activity that requires strength and intelligence! They have often ended up alone and their hard life as fishermen has taken its toll on their health, as the average age is much lower than in other professions.

Unfortunately, real fishermen are becoming fewer and fewer, and the "pond" is increasingly depopulated of those fishermen who looked after the fish and the gullets, with the future of their descendants in mind. Over the centuries, there have been few times when these fishermen have not been suppressed, either by the regime, by their own people or by landowners, with the help of the law. In most cases, the fishermen lost out, being at the mercy of one or other people who imposed the pace of their work, the selling price, made fishing conditional on other hard labor such as reed or ice harvesting, or banned them from fishing if they rebelled against inhuman conditions.

Fishermen since ancient times

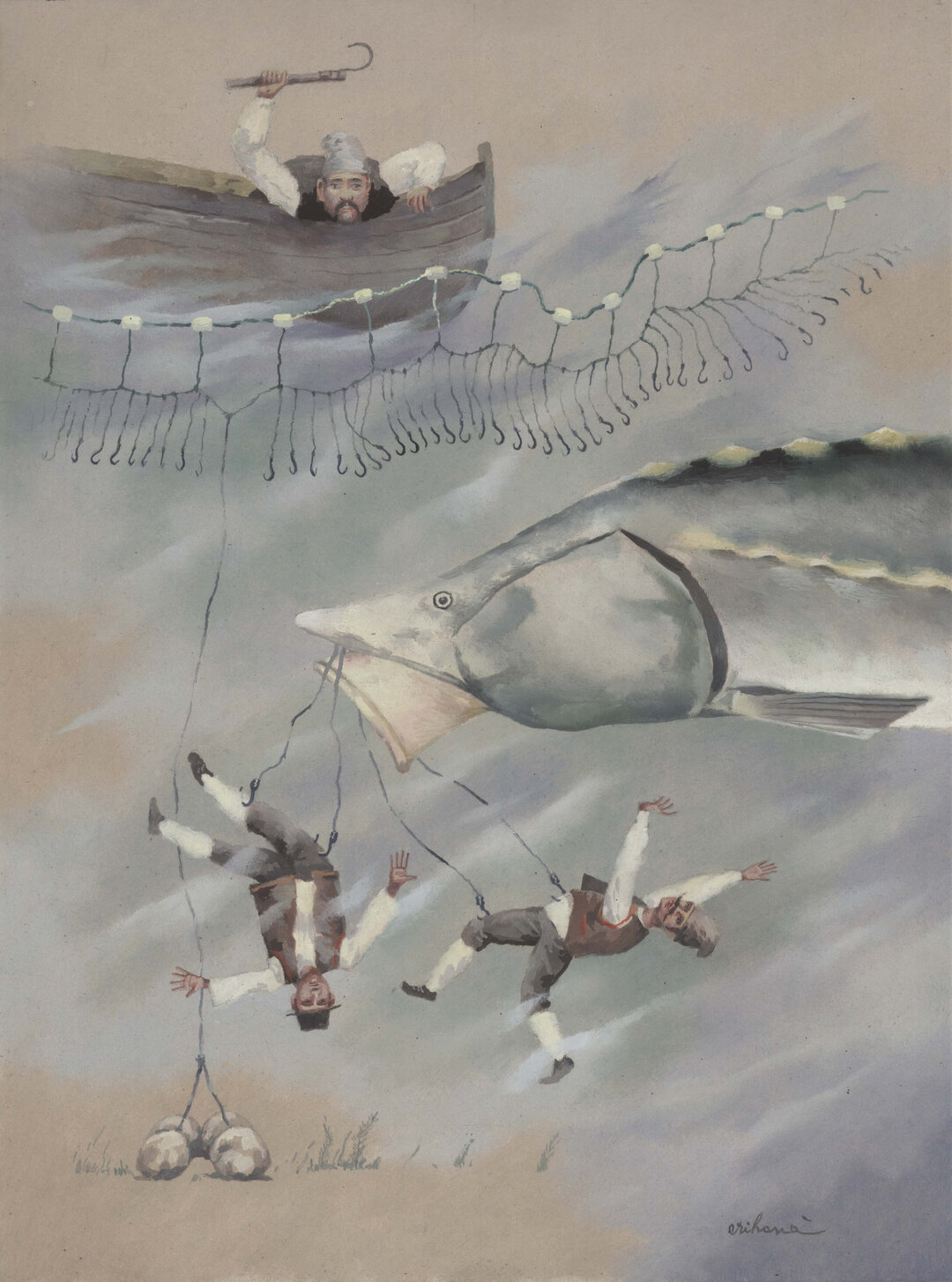

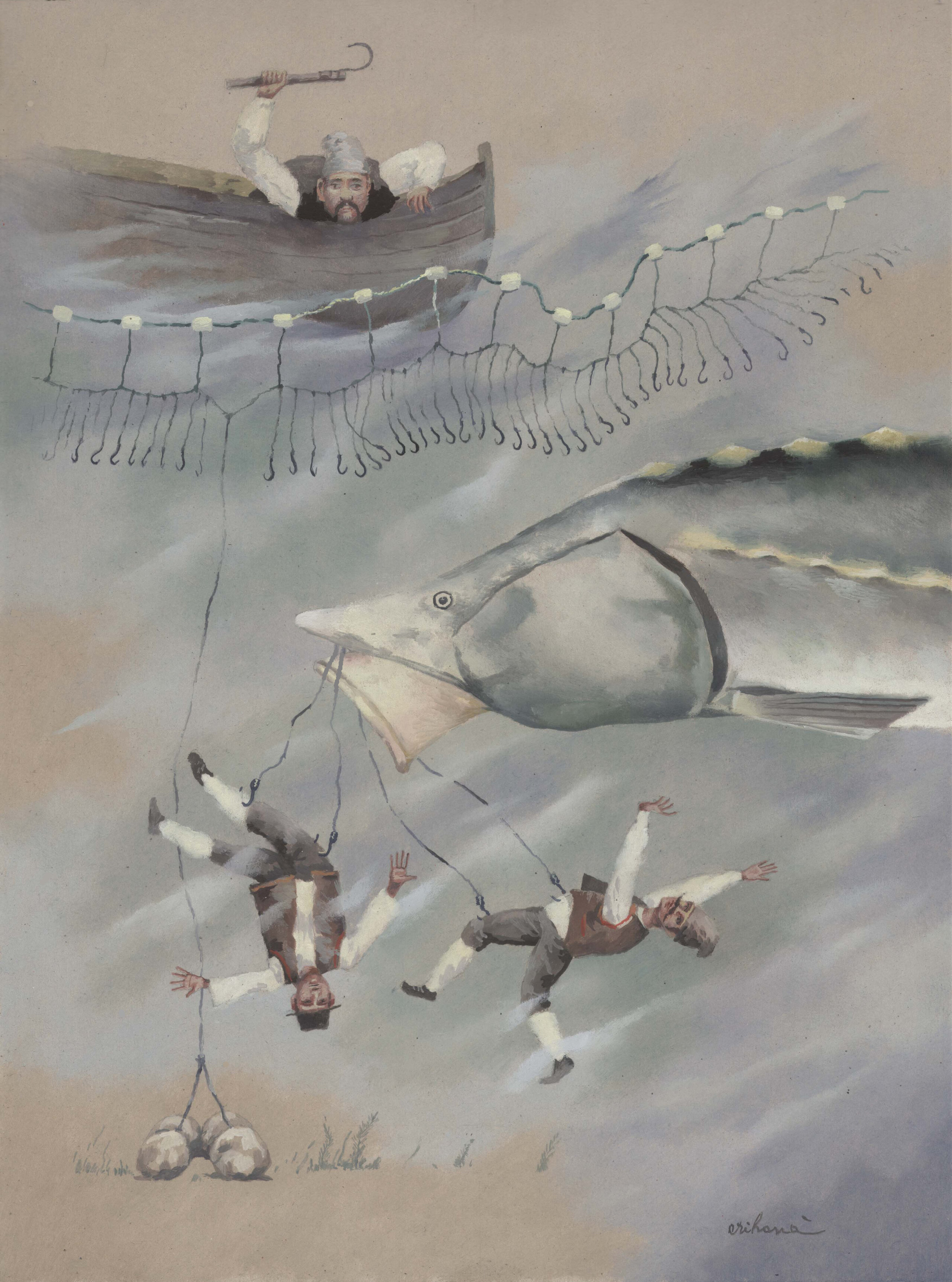

The hunter-fisherman, as described by P. P. Daia, is the quintessence of the traditional fisherman, who inherited from his ancestors this occupation for which he never stopped fighting, as it was the only source of livelihood and the spiritual legacy left down the ages. "The fisherman by nature is a bohemian, he loves his job because it is embroidered with surprises that excite him. When a fisherman paddles through the willows in the morning, returning from his search for the wels hidden in the nooks and crannies of the gullies, a child's joy is imprinted on his face and it is then understood that he has had a bountiful catch. The psychological state of the carp fisherman (the one who catches sturgeon with hooks or carmacles) is very characteristic, as he faces the raging waves of the sea with an astonishing resignation and carelessness, leaning on the front edge of the van and pulling the perimeter rope with a philosopher's calm, his eyes fixed on the arrival of the hook that has impressed on him the jerks of the huge morun or the rough sand eel. Beforehand his face is transfigured, his heart beats wildly, a nervous trembling agitates his whole body, and by the time the beast has been subdued, the fisherman is the happiest mortal. The fisherman is an individualistic worker par excellence in all kinds of tools, except the net, when he has to work at the so-called "Opușini" fishing, although due to the concession of the pools to fishing companies, the individualistic character has begun to weaken. The most skillful and intelligent seek out the most productive fishing spots and do not allow others to sit next to them, whom they know to be incapable in the art of fishing or to be unlucky. For this reason it is not easy to group them into cooperative societies. The love of fishing is ingrained in the souls of the riverside dwellers by inheritance, so that they should be very quickly methodically trained in modern fishing skills" .

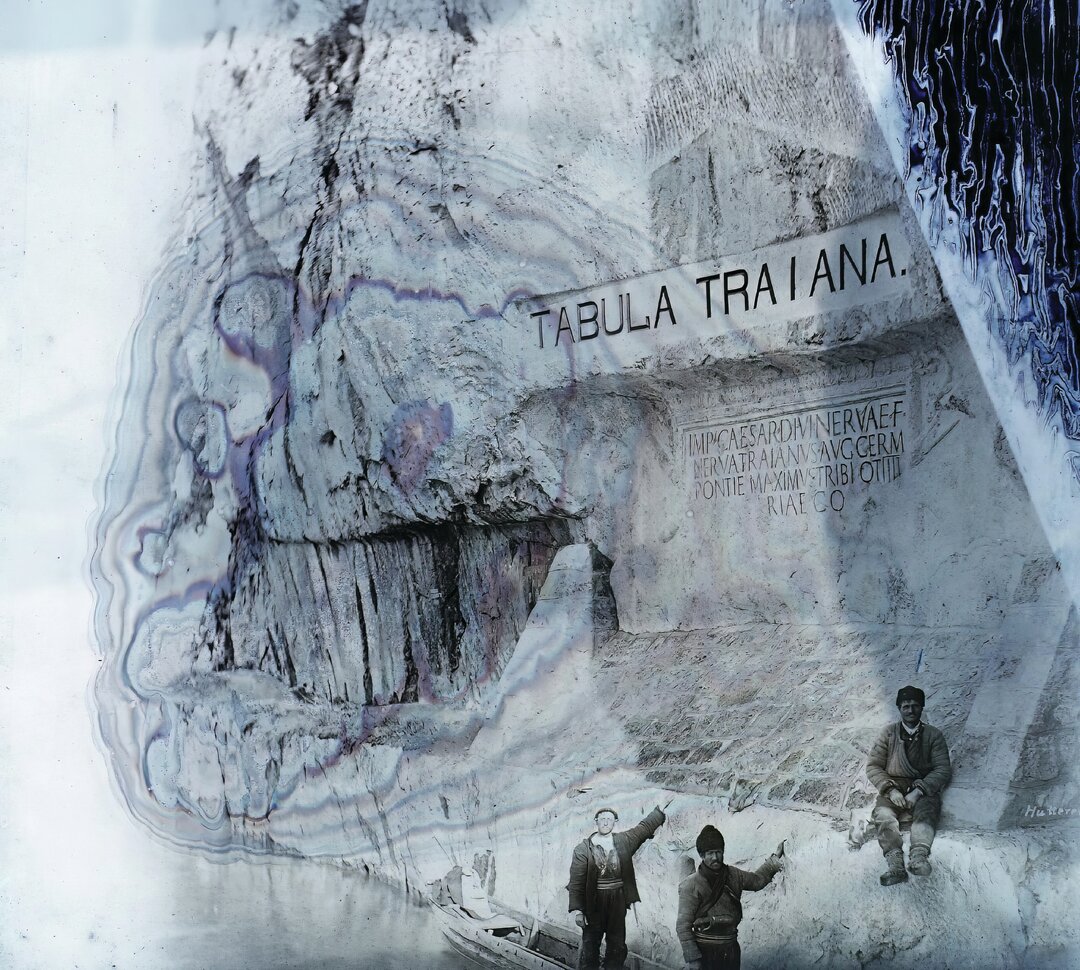

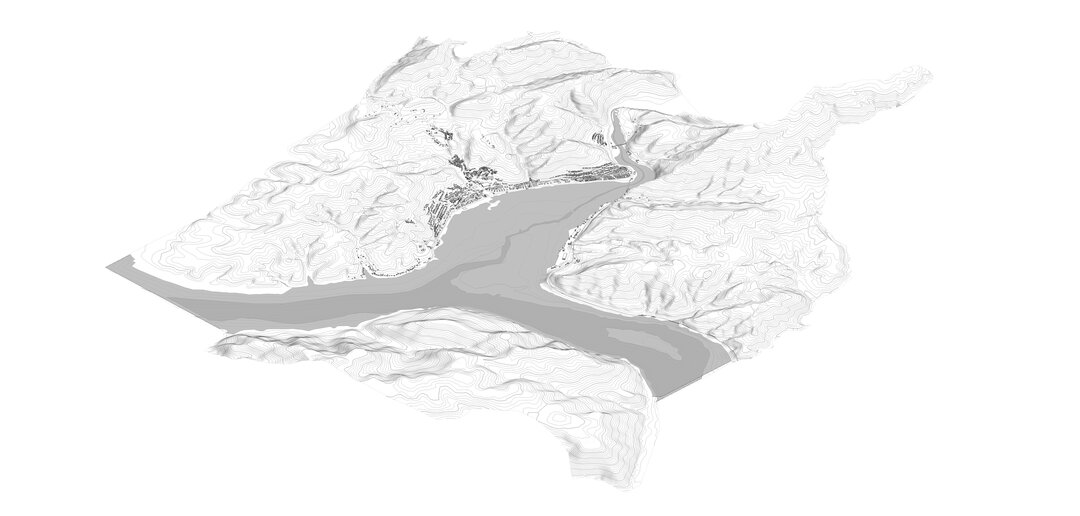

For generations, since Neolithic times, when the first Danube riverside communities fished with archaic harpoons made from deer antlers, Schela Cladovei, a 10 000-year-old settlement, was home to prehistoric inhabitants whose main occupation was fishing, especially for sturgeon, which was the main source of protein at the time, as evidenced by the numerous sturgeon scutes collected from these sites.

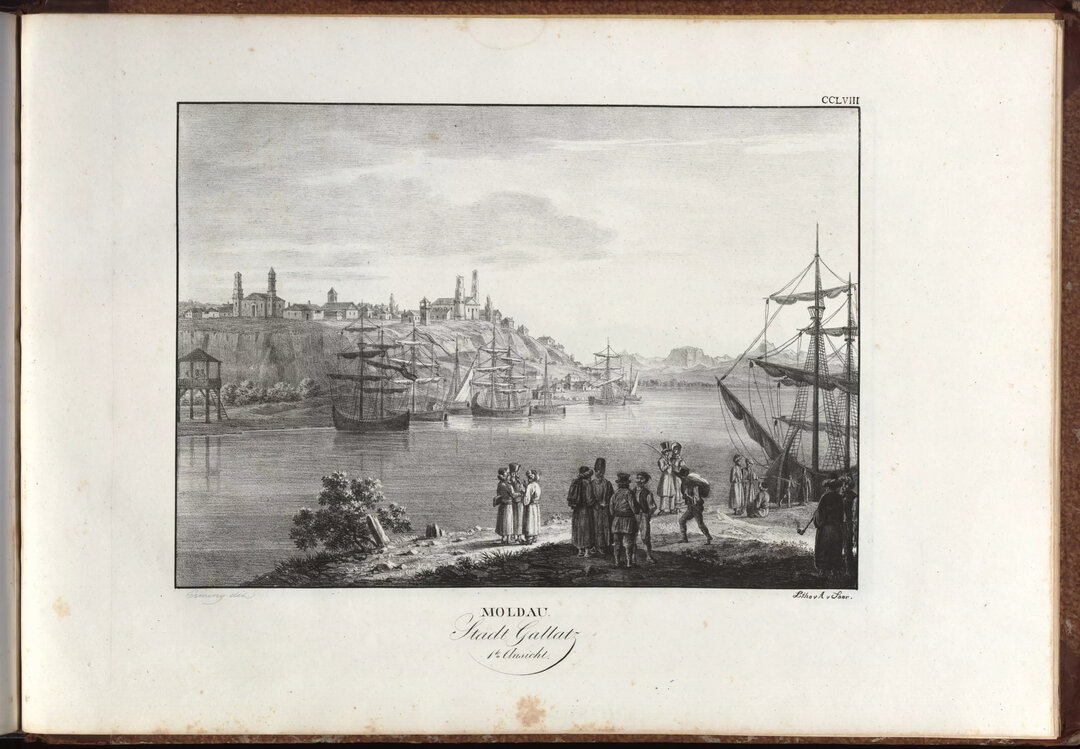

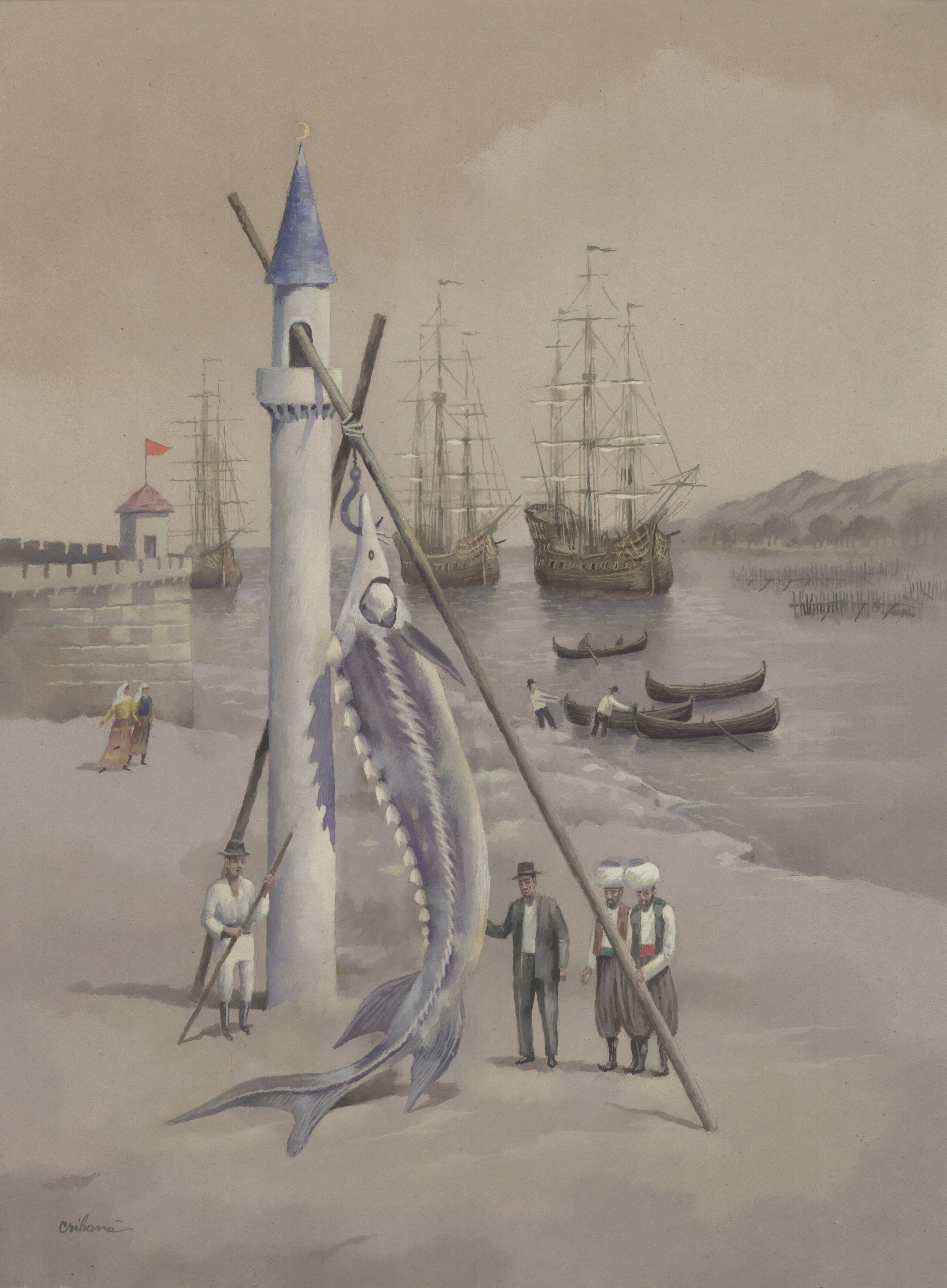

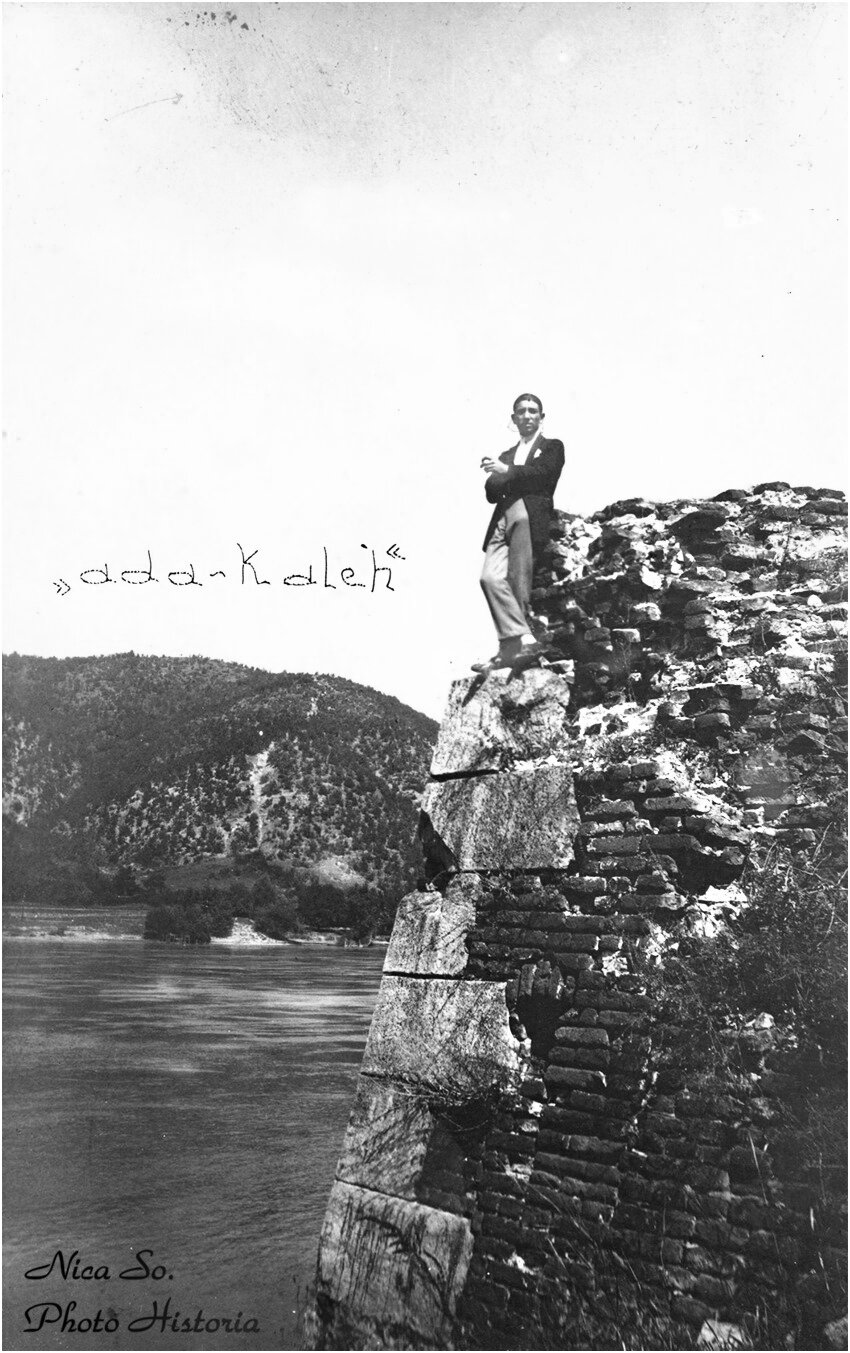

The geographer, astronomer, hydrographer, historian and physicist Luigi Ferdinando Marsigli, in his 1726 work 'Danubius Pannonico - Mysicus', gives details of his time on the island of Ada Kaleh in 1690. Every day, fishermen gutted 50, 60 and sometimes even 100 morunas. This confirms the later observations of Grigore Antipa, who told us that the Iron Gates area was an area with cataracts and fords and therefore with areas suitable for sturgeon reproduction, but which disappeared with the construction of the two dams (PF I and II). He also notes that the largest sturgeon caught in the Danube weigh 11 pounds (approx. 6 kg), three of which are roe. In the case of morun, he notes that two fathoms in length and weighing five to six hundred pounds are often caught, but exceptionally a specimen weighing nine hundred pounds (approx. 500 kg) was sold in Vienna. In volume IV of his Danubius Pannonico, Marsigli presents an engraving depicting the 'wealth' of sturgeon fishing in the Iron Gates area. In the boat you can see the fishermen 'spending' the fishing gear in order to remove the captured fish. This also reflects the need for two other boats, which were used to transport the captured specimens, ensuring a continuous flow for the three people who were in charge of cutting them up and preserving the caviar in barrels.

In addition to the abundance of specimens "hunted", it also gives us technical details of the fishing methods used by the fishermen to catch sturgeon in particular. The fishermen used a trapping gear, built on three supports in the shape of the letter 'A', with a net attached to the upstream side so that the wooden frame provided rigid support.

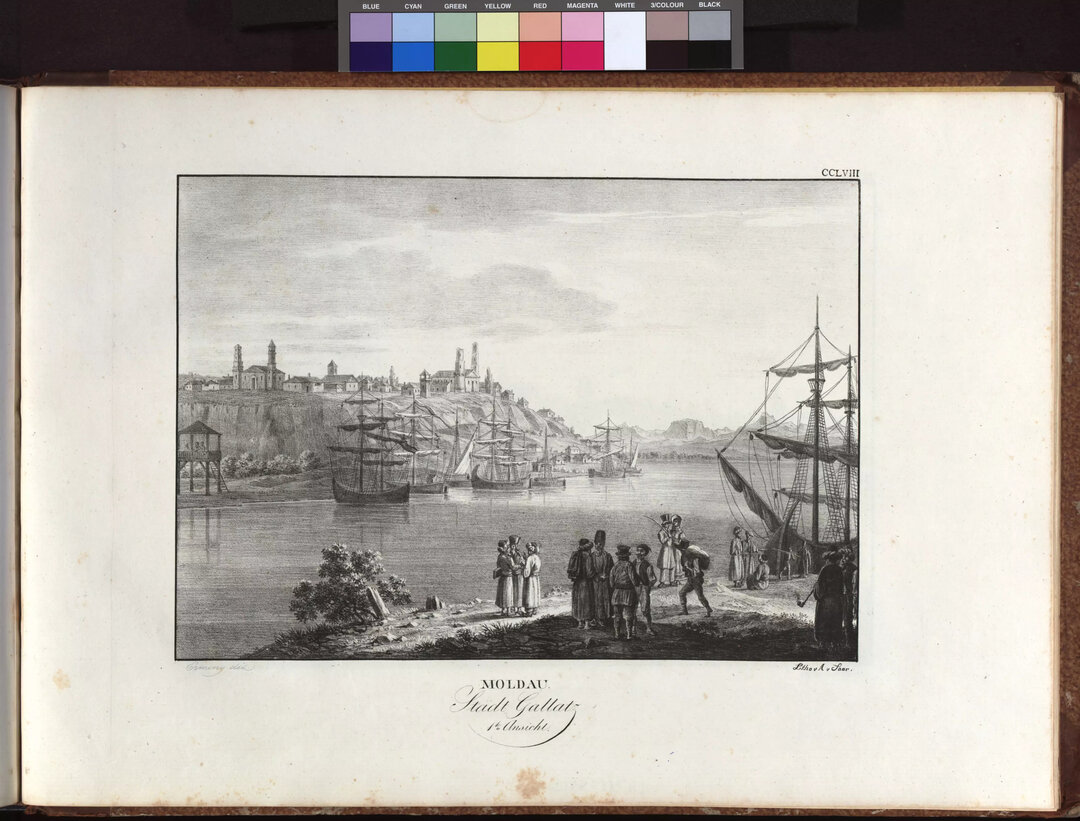

Ever since Dobrogea was not Romanian territory, the Turkish administration has attached great importance to fishing, which is why the dregency, headed by an agă and several bulibași, was in charge of collecting the customs and rent, as well as maintaining the pools.

Evlya Celebi, the most famous Turkish traveler, during his journey in Dobrogea, between 1651-1655, noted: "When spring comes and the ice on the Danube begins to break up, an intendant from the High Porte hires fishing in the Danube. First of all he had oak and hornbeam poles, each eightyarches high,5 cut down from the forests of Galati, in the land of Moldavia, and brought them to Silistra, with the help of 2,000 men and many hundreds of skilled merchants. They put them into the Danube, starting from the two banks towards the middle, and leaving room for only one fish to pass. Then they weave between them poles of wicker, starting from the bottom to the top, and the weaves are only visible above the water. Then they leave a hole, which they close with a door, also made of wicker. For passing ships, they open this door and close it. In front of this little gate, the fishery steward has rooms and cafes built on stilts of water, with interiors and exteriors worth seeing. Here this one lives with his 100 men... When the moray eels arrive in front of the Talwan in front of Silistria, they see that the water is closed and eventually they turn back, but when they arrive they leave the braided port of the strait, they crowd in there, and when they try to turn back again then the braid is lifted, and after all the fish large and small are taken, the braid is left in the water again... By the will of Allah seventy large moray eels have fallen into the net, each one is eight to nine arshins long, and from the belly of each one five to tenscales6 of roeare taken out."

The fishermen hunters, as they were called at the beginning of the 20th century, were scattered all over Romania, but mainly in the settlements along the Danube, from the Iron Gates to the sea. They were of different nationalities, each with customs specific to the areas from which, for various reasons, they migrated to these lands. From Silistra upstream, the majority were Romanians, and the most famous for their skill were the Turtucai, who fished in all the pools in the floodplain.

As we move towards the Black Sea, the native Romanian fishermen were replaced by other nationalities. In 1909, there were 5,231 fishermen working in Tulcea county, of which only 1,279 declared themselves Romanian. The most numerous were Lipovenes, Cossacks from the mouth of the Don. They were Russians of the "old law" (staro-obrkhaz or staroveri), divided into several faiths (popovites - with a priest, bezpopopovites - without a priest, Molocans, etc.) who left Russia for Turkey, but some of them settled at the mouth of the Danube, especially in Jurilovca, Sarichioi, Tulcea, Brăila, Ismail and Vâlcovo.

Another community, quite numerous in the Danube Delta, is that of the Zaporozhnian Cossacks (Haholi, Malorussi or Small Russians) who left the mouth of the Dnieper in 1775, numbering 8,000, and settled at the mouth of the Danube. Not getting on well with the Lipovans, they migrated in 1785 to Banat, near the Tisza, from where they returned in 1813 and settled mainly in the villages of Catâleț (St. Gheorghe) and Danube, bringing with them their skills in fishing for sturgeon, especially morun.

The most favorable area for sturgeon fishing was in the Black Sea, at the mouth of the Sf. Gheorghe Arm and we can say that it was the most important area for sturgeon fishing in Romania and in the entire Danube basin. In the marine area, between Sulina - Sf. Gheorghe - Gura Portiței, more than 80% of the total amount of sturgeon was caught, far exceeding the other areas (about 1,400 tons of sturgeon were caught commercially in 5 years in the Sf. Gheorghe area). The same proportion is maintained for black roe, more than 80% came from this area, especially the Sf. Gheorghe area, where in 5 years (1920-1924) about 47 tons of black roe were reported. However, real fishermen from this area have kept in their blood the fact that these species must be protected with sustainable and selective commercial fishing, and the measures banning commercial fishing have directly affected them. (Sf. Gheorghe City Hall)

With the introduction of the Fisheries Act in 1896 new fishing methods were developed. The Zaporozhnian and Lipovanian Kazakhs brought with them the science and the necessary tools, gill nets and reels, for more efficient fishing in the Danube and the Black Sea.

In the Black Sea, fishing grounds were located close to the shore, in water depths of more than 10 meters, where experienced fishermen fixed the strings of reels with stakes driven into the seabed by beating them into the sea bed. These were fixed, and every few days they were 'spent' to check the sturgeon hooked on the hooks. They were left in the sea as long as their functionality was not affected by storms or as long as it was not necessary to sharpen the hooks.

The Danube was also fished by Turkish and Tatar fishermen left over from Turkish rule in Dobrogea or who came specifically to fish for turbot. There were also Greek fishermen on the Black Sea, descendants of the inhabitants of the ancient Greek cities.

Antaceans, as sturgeons were known in the 5th century BC, are characterized in early documents by Herodotus as "large boneless fish", which were found in very large numbers at the mouth of the Danube. According to the writings of some historians, in the 5th century BC there was a veritable sturgeon cult in the area of Histria (in today's Constanta County), including the coin of this city, which depicts on its reverse an eagle holding a fish in its claws, which is most probably a sturgeon by its shape. The same theory is supported by the discovery of two bronze coins in the city of Panticapaeon (Kerci), which had a sturgeon, most probably a nisetrus, depicted on the reverse. Just as the Constanța Casino is a true symbol of the North-Western Black Sea, the sturgeon is the symbolic species of the Danube and Black Sea fisheries.

The prejudices of other times

Unfortunately, the simplicity of the fisherman, in the purest sense of the word, was a source of profit, not infrequently for the tenants or the cherhanags, turning them into slaves. As proof of this is a letter from 1869, from a group of fishermen from Dobrogea, who complained to the agă about the tricks that the tenant-landlord played in order to get the lowest price for their fish.

The servants' claim is that:

"The undersigned being all fishermen hunters, we submit to your kind knowledge that although on the basis ofour previouscomplaint, by which we complained against the contractor of charging us the fishing dijma that he was taking a lot of extra money from us under the pretext that he was charging the dijma, a committee was ordered to be set up to fix in either which month under the dresare of minutes, the price of the fish and to arrange the matter of fishing, However, the said commission did not investigate and establish the price at which a hundred or so ocals of fish were sold during the month at the municipal markets in whose waters we fish, but instead drew up minutes noting the price at which the fish was sold at the Tulcea market, since the entrepreneur, for his own intrigue and profit, sent some partisans to buy fish at a higher price, which he then presented to the commission, which on this basis concluded the minutes. - Now the fish for the month of March he claims and collects from 130 piasters per hundred on the basis of the minutes concluded two months earlier, while during the month of March, at some scaffolds a hundred octares of fish was sold for 20, at some for 30, and at others for 40 piasters, on which it was not possible to obtain higher prices than these. So, taking all the scaffolds together, he charges the dijma by reckoning the price of the fish at 130 piastres per hundred octares.

This burdens us too much, and if it goes on like this, we cannot open our eyes from our debts, and we shall ruin ourselves altogether. - Apart from this he is collecting the dijma in kind according to the law, from some localities 20%, from others 25, 30 and 40, in a word he takes as much as he can.

Submitting all this to Your Excellency's high knowledge, we ask you with the deepest respect to kindly intervene to take from us the tithe in kind of 15 percent, according to the law, while at the same time taking measures and finding a way, so that we can save ourselves and escape from the robbery and ruin that threatens us.

April 12, 1869

Costache Erghindă, Filip Naum, on behalf of all fishermen, Mihail Kiriac, Vasile Nedelcu, Gheorghe Mihail, Ermalai Nichitov, Luca Varion, Gheorghe Kirioz, Serghei Ivanov and others".

In the Delta at the end of the 19th century, there were two kinds of people engaged in fishing: fishermen themselves, who caught the fish, and cherhanags, who took the fish, preserved and sold them. The fishermen were simple laborers who caught the fish with other people's gear and were either employed or self-employed, with their own gear and the ability to sell the fish themselves. Cherhanags were also of several kinds, some who were only in the business of money speculation and begging, giving fishermen money in times of need or giving them products, especially drink, on debt, most of them being tavern keepers, and taking all the fish from the fishermen at very low prices. The second category were the big fishermen or entrepreneurs who had a real fishing household with fishing gear, a fishing hut, ice-box, ice-box, salt-cellars, and spawning facilities. As Antipa describes this activity, 'if the former are parasites of the puddles, living by begging off the fishermen, the latter play a very important role'.

There has been no shortage of cases in which certain individuals have taken advantage of fishermen's naivety or precarious financial conditions, making them dependent on them. There are multiple examples, one of them happened in 1908, when a fisherman catches a catfish at St. George's with a fishing gear rented from the fishmonger. The latter values the fish at 30 lei, of which he actually pays the fisherman a part, and he keeps 2 parts of the value of the fish, the countervalue for the gear. The fishmonger sold the fish to Galati, where he received 50 lei, i.e. the fisherman received 10 lei and the fishmonger 40 lei.

A famous story of those times is described by Paula Grațiela Cernamoriț in 'Sfântu Gheorghe-Deltă-Studiu Monografic', who notes that in 1860, in the locality of Sf. Gheorghe, there was a fishmonger Costenco's cherhana, and in 1862 two more cherhanale were opened, owned by brothers Costache and Neculache Valsamache, who sold fish in Galati and Greece. After Costenco's death, the heirs fell into the habit of drinking and became indebted to Iani Malanos, who was engaged in the alcohol trade in Tulcea. They soon lost everything to him. In 1869, he began to make a profit and soon took over the Valsamache brothers' business, monopolizing the fish trade in this extremely prolific area. The journalist Victor Crăescu wrote in 1894: "The whole village is a fishery, and its master is Iani Melanos... Milan, a dog and a half, and all the fishermen of Cadîrlez are in his hands. He has 10 traps and almost the whole village is in his debt". Sadoveanu also wrote about Milan: "There is a certain Iani Milan here, living and enjoying good health. He is one of our citizens. A street in the fair bears his name. He is an old white, handsome man; he looks peaceful and serene; he is now almost retired from business, and you see him walking in the sun, with his hands behind his back, thinking of something, perhaps something pious, some benefaction, the immortality of the soul.... That bastard, gentlemen, is Iani Milano. How much he exploited people, how he oppressed and mocked them, only the good Lord knows."

The fisherman hunter, a memory?

The fishermen practically merged with nature, learned its laws and gave it due respect, they were always hunters and not gatherers. How beautifully Antipa describes the fishermen as hunters: 'Incidentally, in every fishing tool that I have described and in all the systems of exploiting our fisheries, one could see the gift of observation and ingenuity of our fishermen, for, after all, everything is the product of their minds, of the experience and observations accumulated over many generations. The fishermen have become great connoisseurs of nature, so that they can master and use it for the necessities of life. All these many observations of life in the water and on land in the Danube region have greatly increased the intellectual capital of our fishermen, developing their intelligence and sharpening their senses'.

Tradition, religion and perhaps isolation have held these communities together, with a strong sense of orderliness, which at many times seemed to us Venetians to be a picture from another world. Often when you arrive in their midst time starts to become relative, suddenly slows down, and the endless stories take you into another world, a world only of fishermen and traditional fishing communities. You still meet fishermen today who live according to the old ways, who cry when they see the empty creels and think of the abundance of the past, and at the same time lament the future - "the pond has no fish".

I remember a story that has stuck in my subconscious. I once asked a real fisherman if he had caught any sturgeon (this I allowed myself long after I had met him):

- I caught an 80-pound morun some years ago. It was a male.

- What did you do with it? Did you sell him?

- What am I, the ox of the pond? Sell him and then buy my own parboise? No, I dried and smoked him in the attic, and all winter my old maid and I cut a slice every morning and we lived well!

He caught what he needed to live, and that's what it means to be a real fisherman, with a sense of order and a sense of the times to come.

The ages and times in which we live have also left their mark on this guild, there are fewer and fewer of us who have inherited this profession, with all its human-nature load. The connection between nature-fish-fish-fishermen (habitat-fish stocks-fishermen), as the primary elements of sustainable fishing, is increasingly weak and the balance is increasingly precarious. This profession is increasingly invaded, like others, by dubious characters who have turned money into God and conscience into smoke.

With their last breath, the wise ones left behind should give birth to a new and fresh impetus and pass on to their descendants the teachings of their forefathers. The situation is unfortunately gray, no custom is of no interest, they fish anytime, anyhow, indiscriminately, nature and its descendants, just for the sake of money and the present, is crumbling utterly under their footsteps.

NOTES

1 Popular names for the winds of the Black Sea coast. Moreana - SW wind that brings moisture and rain; Pureaz - NE wind that is the most frequent and strongest, summer brings drought, and in winter dry frost, it is considered the most favorable wind for fishing; Vastok - E wind, it is a strong wind that acts more in the warm season, it favors fishing; Abazia - it is a SE wind, it is a favorable wind for fishing.

2 Total gear, facilities and personnel needed to fish with 300 perimeter of karma (perimeter of karma = 25-30 hooks). There are fishermen on a Danube trawl with a boat and a cook. One of the fishermen is the fisherman or Atamanul, who is usually a fisherman skilled in catching morun.

3 German pound - equivalent to 560 grams.

4 If it is the Austrian fathleneck, it measures 1.896635 m. (https://ro.wikipedia.org/wiki/St%C3%A2njen)

5 Arșin,arșini (Russian: Arșin) - a unit of measurement which, converted to 0.711 m.

6 Cantar( tc. kantar) - A unit of measurement equivalent in medieval Moldova to 45 ocal, or about 57.5 kg.

7 Aspru was a Turkish coin widely circulated in Walla Wallachia in the 15th-17th centuries, one aspru had between 1.15 and 1.2 grams of silver.

8 Gazzetta, Venetian silver coin minted in 1539.

References

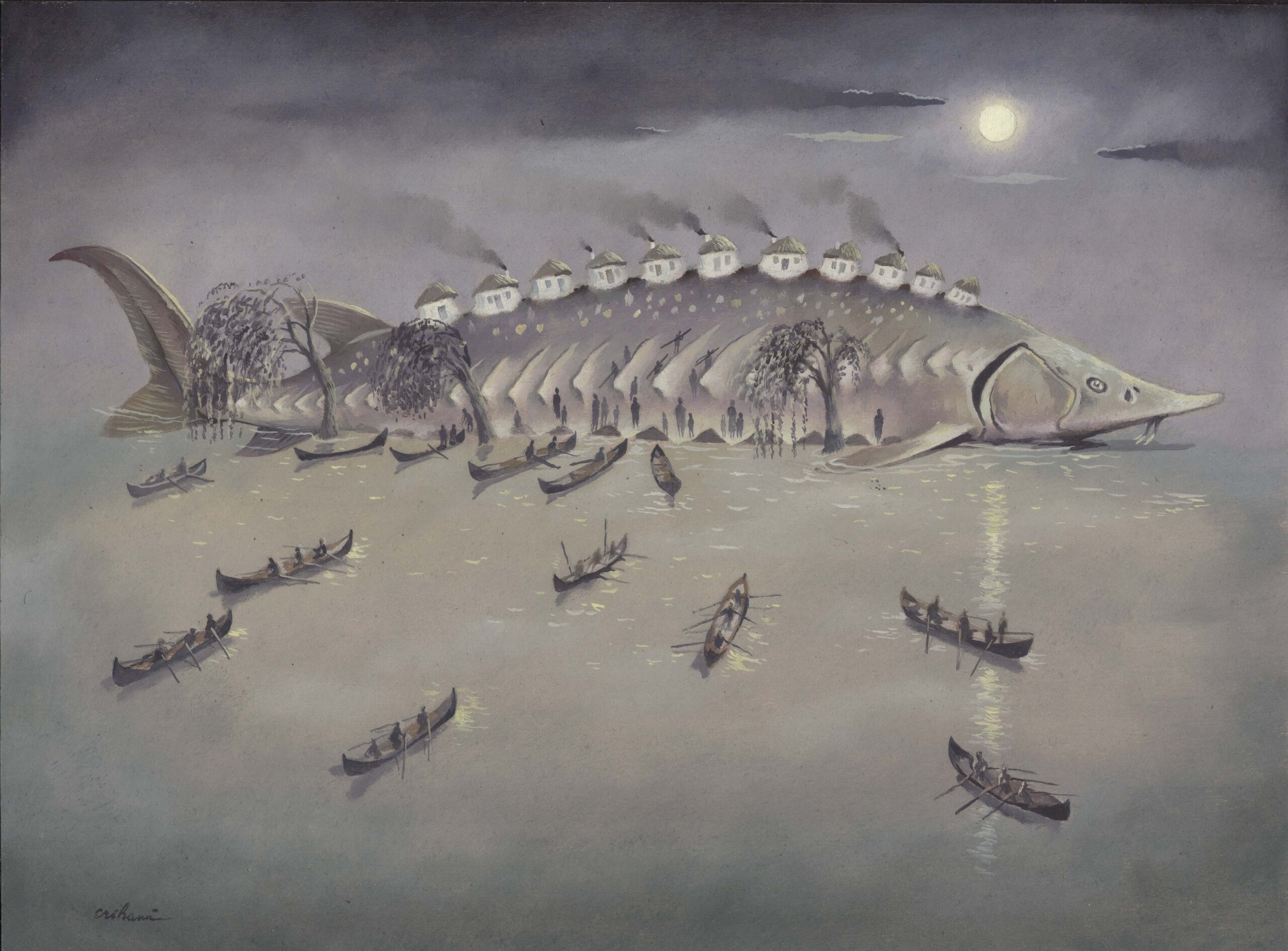

- F. D. Crihană and T. Ionescu, Artists, Danube Delta, the Magic Heritage. [Art]. Aquatic Biodiversity Center, 2023.

- P. P. Daia, EXPLOATAREAPESCĂRIILORSTATULUI, București: TIPOGRAFIA "D. M. IONESCU", BUCURESTI, 1926.

- G. Antipa, Pescăria și Pescuitul în România, Tomul VIII-No. XLVI ed., București: Romanian Academy, Publicațiunile Fondului Vasile Adamachi, 1916.

- L. Bartosiewicz, C. Bonsall and V. Șișu, "Sturgeon fishing in the Middle and Lower Danube region", 2008 [Interactive]. Available: https://research.ed.ac.uk/portal/files/539953/039_bartwcz.pdf [Accessed 11 10 2018].

- L. F. Marsigli, Danubius Pannonico-Mysicus De piscibus in aquis Danubii, IV ed, Amsterdam, The Hague, 1726.

- I. Ionescu, Agricultura Română din Județul Mehedinți, București: Imprimeria Statului, 1868.

[7] T. Ionescu, "THE CAUSES OF STURGEON POPULATION DECLINE IN LOWER DANUBE", in Aquaculture Europe 2022, Rimini, 2023.

- C. C. Giurescu, Istoria Pescuitului și a Pisciculturii în România, București: Editura Academiei Republicii Populare Romania, 1964.

- F. D. Crihană and T. Ionescu, Artists, Centuries of Danube Sturgeon. [Art]. Aquatic Biodiversity Center, 2019.

- M. Holban, Călători străini în Țările Române, Vol. V, V ed: Editura Științifică, 1973.

- A. Piatkowski, Herodotus, Historii, București: Editura Teora, 1998.

- G. Antipa, Fishing Law and the results it gave, București: Institute of Graphic Arts and Minerva Publishing House, 1899.

- P. G. Cernamoriț, Sfântu Gheorghe-Deltă. Studiu monografic, Tulcea: Editura "Școala XXI", 2004.

- M. Sadoveanu, Opere 6, București: Editura de Stat pentru Literatură și Artă, 1956.

- G. Antipa, Dunărea și problemele ei Științifice, Economice și Politice, București: Librăriile Cartea Românească and Pavel Suru, 1921.

- W. Pragher, Artist, Valcov [Kreis Tulcea]: Landungssteg, von oben, W 134 Nr. 006251. [Art]. 1933.

- A. Decei, Călători în Țările Române, VI ed: Editura științifică și enciclopedică, 1976.

- M. Ciocanu, "National Museum of Ethnography and Natural History", May 15, 2011 [Interactive]. Available: http://www.patrimoniuimaterial.md/ro/pagini/registrul-fi%C8%99ele-elementelor-de-patrimoniu-cultural-imaterial-cunostin%C8%9Be-practici-%C8%99i-simboluri/unit%C4%83%C5%A3i-vechi-de-m%C4%83sur%C4%83 [Accessed 02 Jun. 2018].

-topaz-denoise-enhance-sharpen--15883-m.jpg)