The bridge of our indecision

-topaz-denoise-enhance-sharpen--15883-xl.jpg)

What unites us divides us

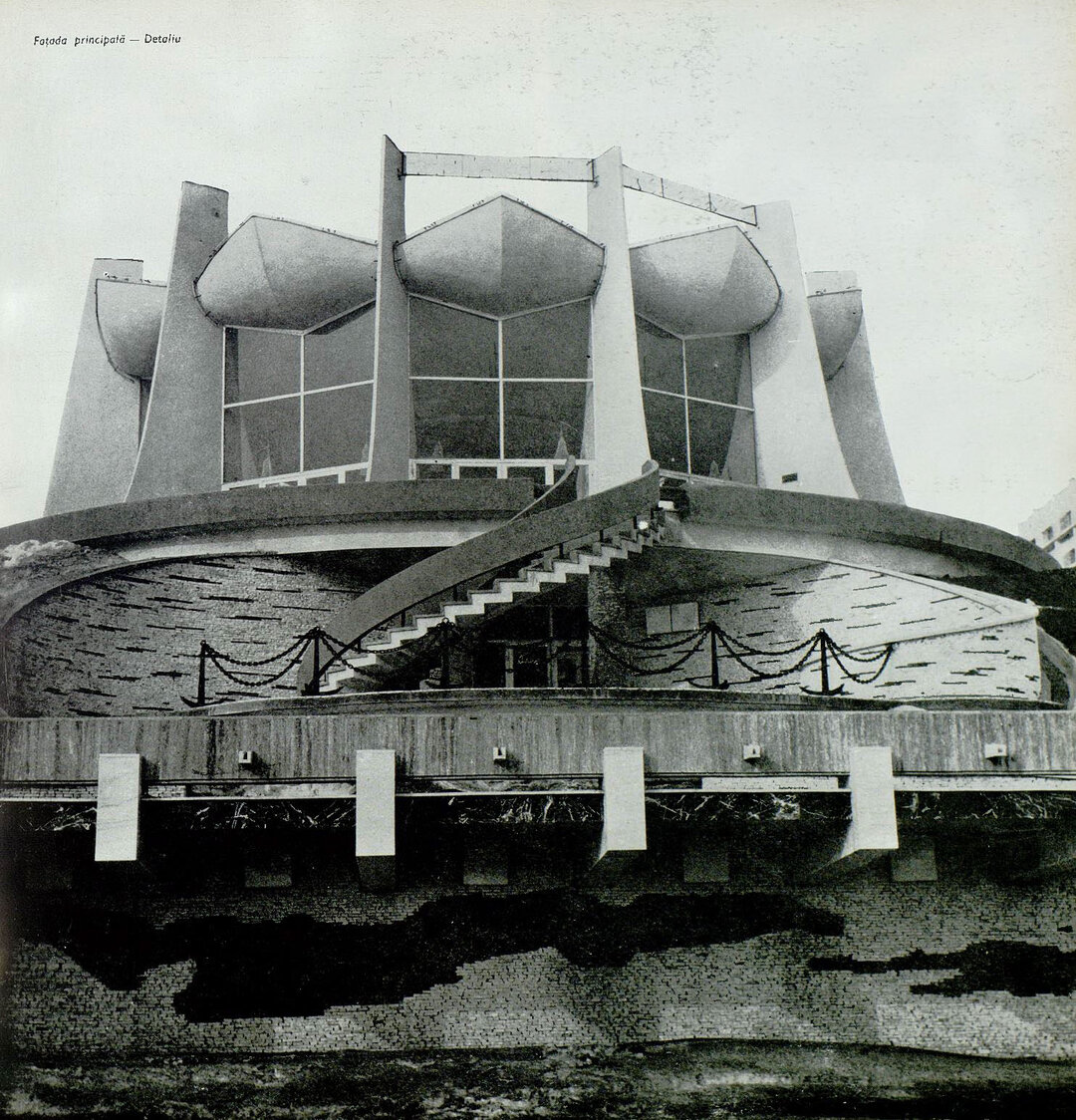

Photos: International Database and Gallery of Structures

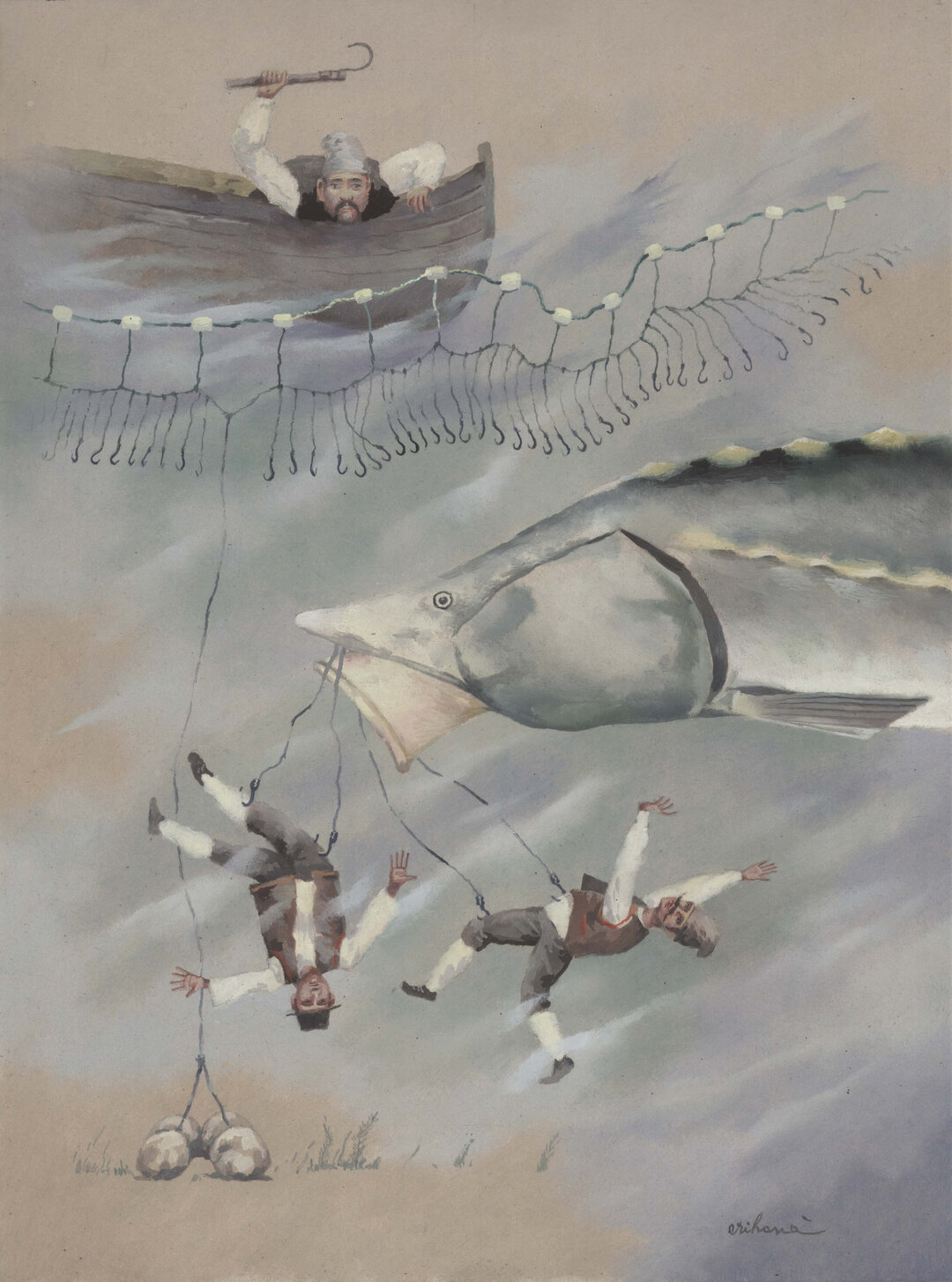

The Danube unites us? Does the Danube divide us? I have never understood exactly what the Danube is doing with us and our neighbors to the south for 470 km. Nor do I understand how it is that both we and others accept, resigned and unconcerned, that the Danube is our border and barrier.

I tried to find some answers between 2001-2004, when I chaired the Joint Commission for the Calafat-Vidin Bridge on the Romanian side and as Executive Director of the Stability Pact for South-Eastern Europe1 on the Romanian side. On the Bulgarian delegation's first visit to the Romanian side, we discovered that our interlocutors came with their families because it was their first time in Romania, although most of them lived in Vidin. Romanian colleagues had never crossed the Danube, even if they were from Calafat or Craiova.

For almost four years I participated in the finalization of the bridge project, which may seem like the height of procrastination if we don't have a brief chronology of events.

What do Apollodorus, Friendship and New Europe have in common?

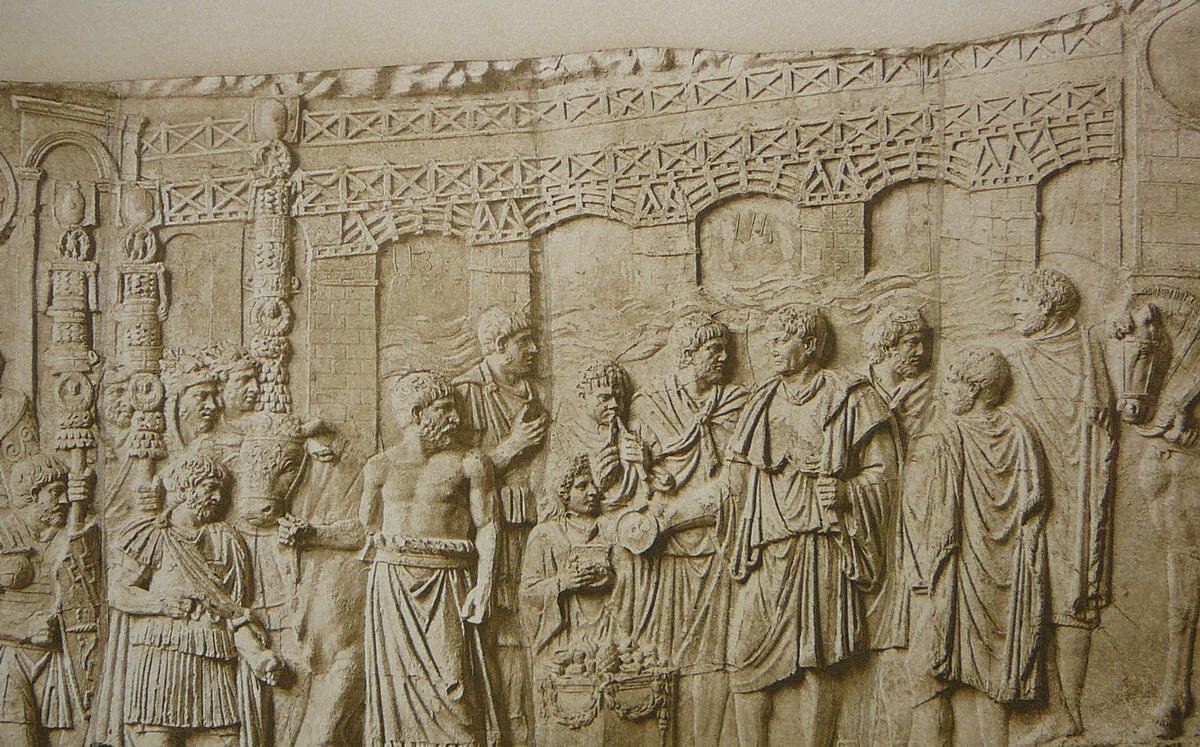

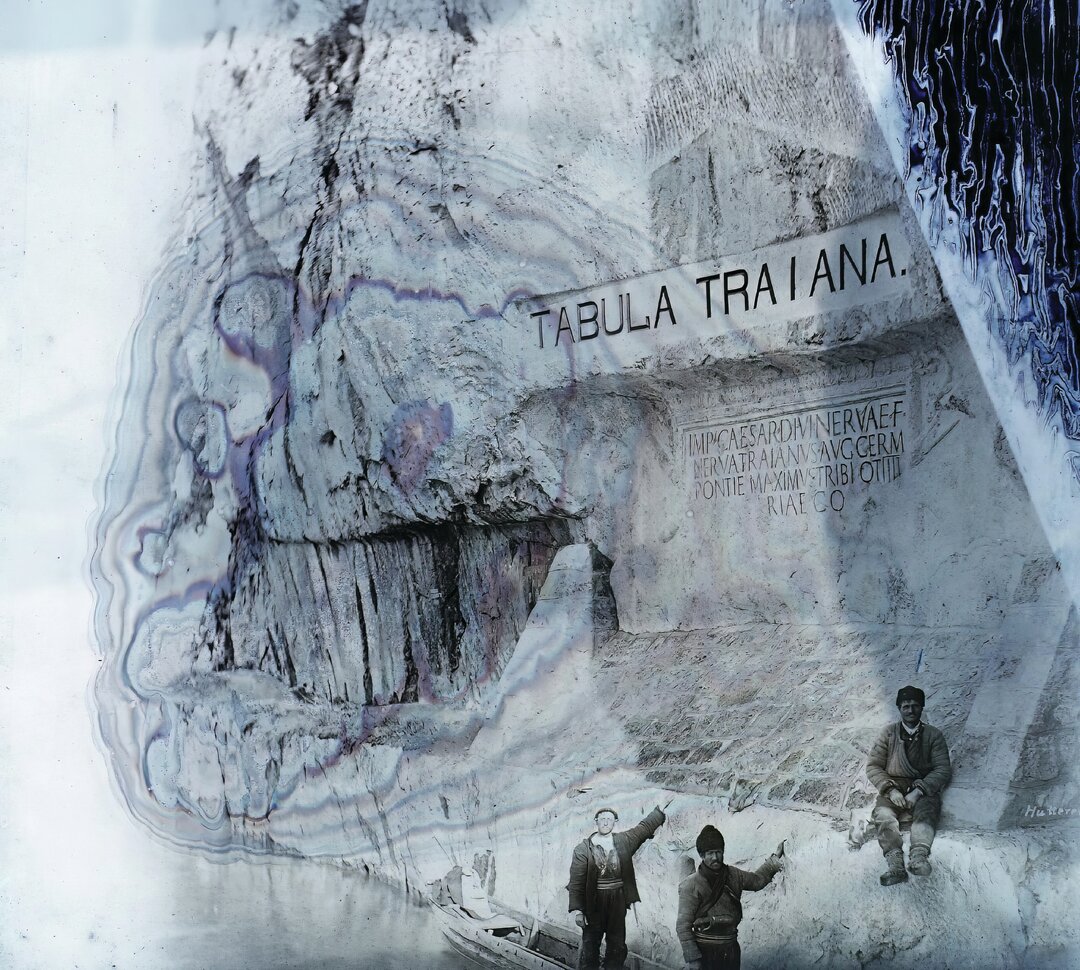

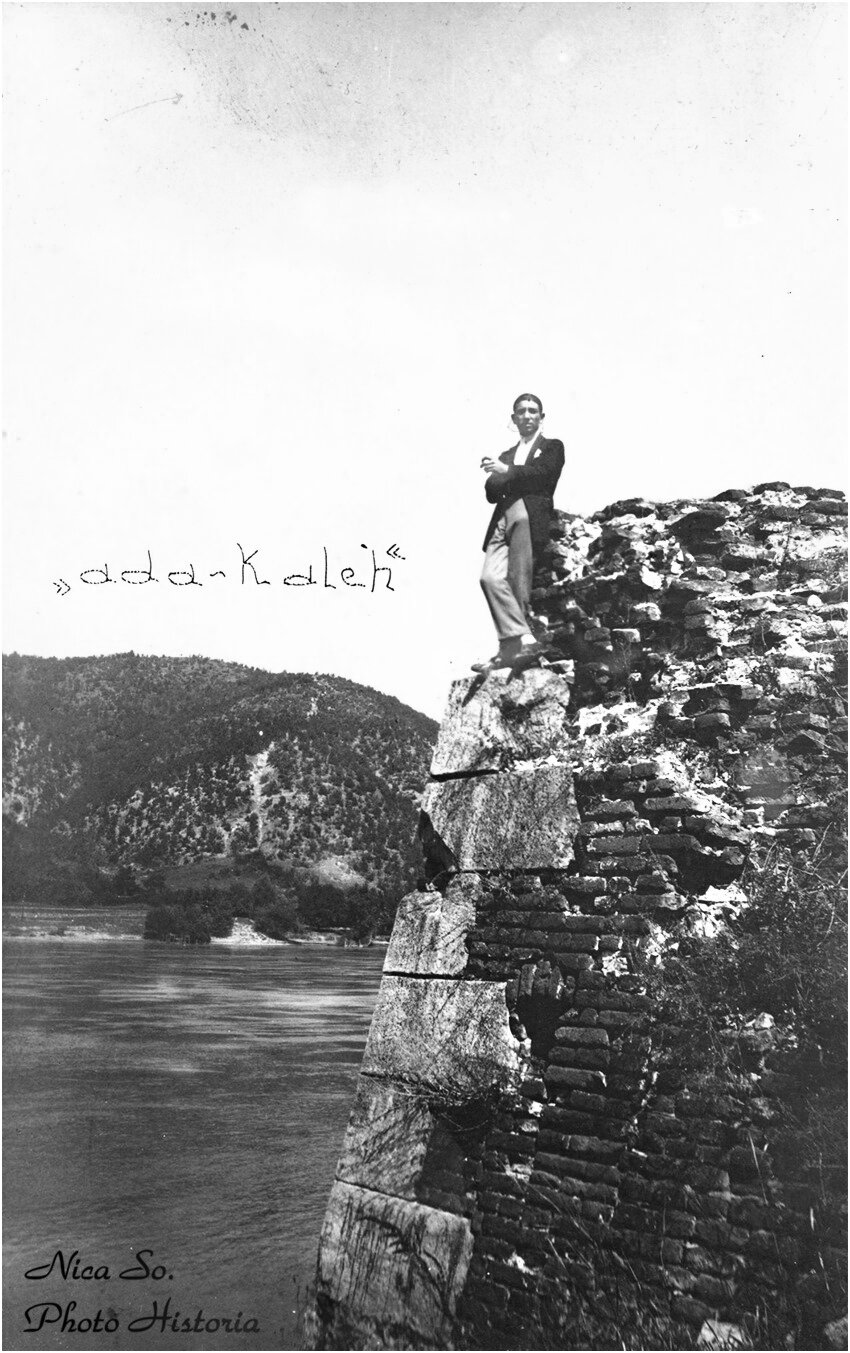

For more than 2,000 years, the only European leader determined on the Danube crossing was Emperor Trajan, who in 103 commissioned a bridge across the Danube from the Syrian architect Apolodorus of Damascus, to be completed between the two Dacian-Roman wars. At Drobeta (exactly where the streams of the Danube from Cazane used to stop), the Bridge2was completed in early 106 and was considered one of the most important engineering achievements of the ancient world. The secret of the binder used is still unknown today, but we still have time! The bridge was instrumental in winning the war between Emperor Trajan and King Decebal. Thanks to the bridge, the Roman army transported across the river the heavy equipment used to besiege the Dacian fortresses in the Orăștiei Mountains.

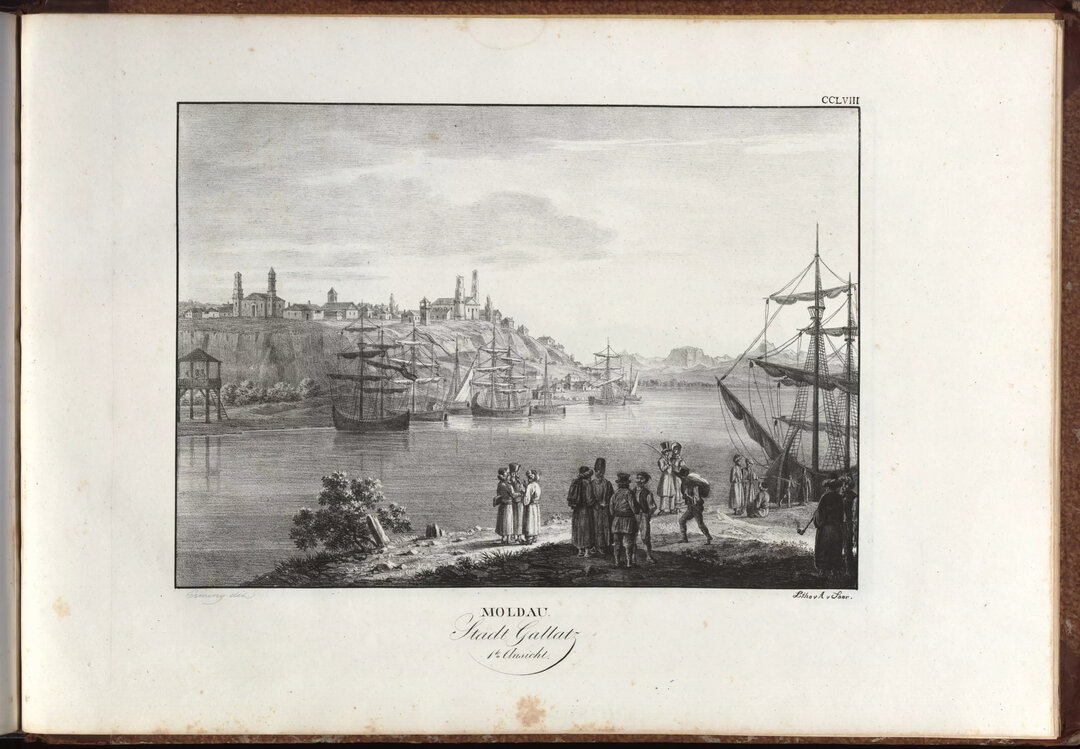

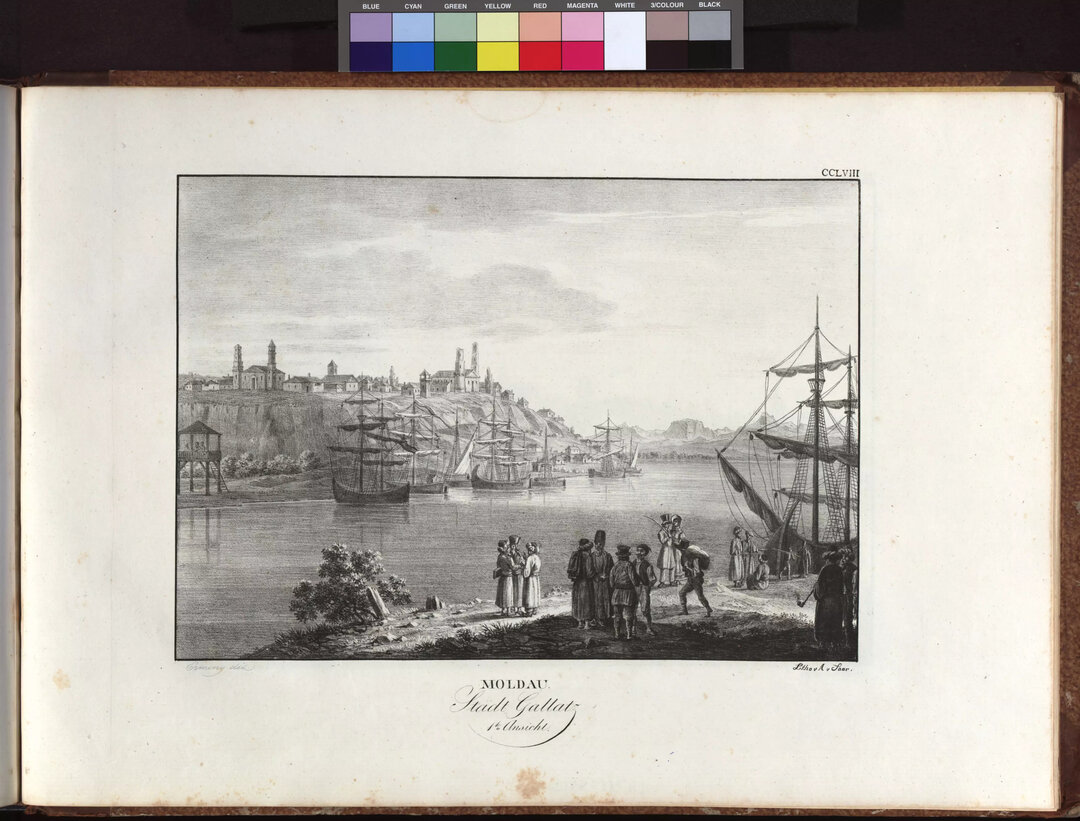

After the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-1878, which led to Romania's independence and the creation of autonomous Bulgaria, the first contacts between the principalities of Bulgaria and Romania, the possibility of building a bridge across the Danube as a link between Western and Central Europe on the one side and the Balkan peninsula on the other was assessed. The intentions had already been expressed at the end of the Crimean War (1853-1856).

It was not until the 1920s that preliminary talks began on building a bridge across the Danube, but the economic crisis and the Second World War again blocked good intentions. The negotiations resumed, 100 years after the talks started, at the familiar pace, until the USSR government decided that the bridge should be located in the Giurgiu-Ruse area and the project and the works for the construction of the bridge should be entrusted to the Ministry of Transport of the Soviet Union. The bridge was commissioned in 1954 and was named "Friendship Bridge"3.

It was the war in the former Yugoslavia that raised the need for a second bridge across the Danube to divert the link between Central Europe and the Balkans and avoid the conflict zone. It was a continental emergency and a local opportunity.

In 1999, the newly-created Stability Pact for South-Eastern Europe (SPSEE), coordinated by Bodo Hombach, organized the first donors' conference, raising some €4.7 billion for the Balkan countries. Hombach was succeeded by Erhard Busek (former Vice Chancellor of Austria and a noted reformer and enlightened campaigner for a united and strong Europe) who focused on the construction of the Danube Bridge 2, which was to make Pan-European Corridor IV4 more efficient. The bridge was to save European transport disrupted by the war and events in Yugoslavia. It was obvious to everyone, but not to the "bitter neighbors" who made the bridge open almost 15 years after the end of the war!

During this time, negotiations between the Danube "neighbors" went through tumultuous stages. The first controversy was over the position of the bridge.

The Romanian side refused to locate the bridge between Vidin and Calafat, as this would remove Bucharest from the transportation corridor to Western Europe and dramatically shorten transit through Romania. Romania would have liked to develop infrastructure in two other directions: 1) Budapest - Bucharest - Constanta - Istanbul, which would have put the Port of Constanta in a key position; 2) Budapest - Bucharest - Giurgiu - Sofia - Kulata - Thessaloniki, which would have maintained long-distance transit through Romania and Bucharest's role as a crucial transportation hub. At bilateral meetings of transport officials, various locations for the second bridge across the Danube between Romania and Bulgaria were proposed: Oreahovo-Bechet, Nicopole-Turnu Măgurele, Vidin-Calafat. In 1994, a PHARE-funded study indicated that Lom-Rast could be the most suitable site, but Romania rejected the proposal. In the late 1990s, Greece, interested in the development of the Port of Thessaloniki as the terminus of Corridor IV, joined the Bulgarian side in supporting the Vidin-Calafat bridge.

In 1998, in Santorini and Delphi, the foreign ministers of the Greece-Romania-Bulgaria Trilateral decided to set up a team of experts to help break the deadlock and in 1999, the Sofia authorities suggested that they could finance the construction of the bridge, with Romania paying only for the access infrastructure on the Romanian side. The Bucharest authorities undertook to look into the proposal!

Romania and Bulgaria have failed for years to reach a common solution. Bulgaria proposed to build two bridges - one at Vidin-Calafat, as the Bulgarian side wanted, and the second, somewhere further east of the river border, which Bucharest agreed to. Romania and Bulgaria were each to bear the cost of their "own" bridge.

In 1999, in Sinaia, President Emil Constantinescu announced that Romania might reconsider its position on building the bridge across the Danube at Vidin-Calafat. A month later, Romanian transportation minister Traian Basescu declared that Bucharest refused to discuss the construction of the bridge at Vidin-Calafat. Thus, in 1999, at the International Conference for the Reconstruction of the Balkans in Thessaloniki, the decision on the new Danube bridge was postponed.

There was speculation that the differences between the two countries had to do with competition over European transport corridors, an economic dispute over electricity exports to Turkey and Greece, and diplomatic rivalry over Romania and Bulgaria's aspirations for Euro-Atlantic integration.

In early 2000, the European Union, through the Stability Pact for South-Eastern Europe, decided to get involved in resolving the Romanian-Bulgarian dispute and Bodo Hombach said: "The Stability Pact cooperation with the Romanian partners is going very well. The Pact is important for European integration. Corridor IV means a lot. We are planning to build a bridge between Calafat and Vidin, which will benefit everyone. The financing is secured. The bridge is a priority project and work can start within a year. If the Romans could build a bridge, we can build one too. A Danube that doesn't have a bridge for 500 kilometers means the Middle Ages for me. We don't want that.

In the same month, Prime Ministers Mugur Isărescu and Ivan Kostov signed in Bucharest, in the presence of President Constantinescu and Bodo Hombach, the agreement on the construction of the second bridge over the Danube in the Calafat-Vidin area5.

In 2001, with German funding, preliminary studies were prepared with the involvement of the Bulgarian company GUS and IPTANA Bucharest, which provided the topographic and geological data necessary for the design.

During 2001-2003, preliminary economic, financial and social analyses of the bridge were carried out, the project's price indices were updated and the "Environmental Impact Assessment Study" was prepared, which was presented publicly in Romania and Bulgaria and approved at the end of 2004.

In 2002, in a PSESE report, the Vidin-Calafat Bridge is mentioned among the objectives supported for Bulgaria, with 2003 as the start date for construction. The deadline was not met.

In 2003, the Bulgarian Ministry of Transport organized the tender for the appointment of the International Consultant (British-Spanish consortium Scott Wilson Holding / Iberinsa / Flint&Neill Partnership), which was to prepare the Feasibility Study in three variants, the Technical Design for the road and rail infrastructure for access to the bridge on the Bulgarian side and the tender documentation for the selection of the builders and consultants. In the same year, the final formula of the bridge was decided. From the "red", "green" and "blue" variants, the "green" variant was chosen with a four-lane road bridge, a railroad track, sidewalks, a bicycle path and a shared border railway depot. The roadway was set to be 1,440 kilometers long and the railway line 2,480 kilometers long.

The Bulgarian side undertook the design, construction of the bridge and the road and rail access infrastructure to the bridge on the Bulgarian side: new rail freight terminal and 7 km of new railway track; reconstruction of the existing passenger station and construction of 4 new road junctions.

The Romanian side was responsible for the construction of 5 km of railway from the bridgehead to the existing Golenți-Calafat railway, 5 km of express road and a station for joint traffic control and toll collection. The 2/6 (discounted) euro per car was ceded to Romania in exchange for granting approval for the construction of the bridge.

In June 2004, Prime Ministers Adrian Nastase and Simion de Saxa-Coburg Gotha met in Calafat, on the site of the future bridge.

Once the site issues had been settled, there were the tender issues. While the Bulgarian side's award of the bridge construction contract to the Spaniards from FCC raised no suspicions, the tender organized by the Romanian side to appoint the consultant stirred controversy. Disqualifications, under-assessments, over-assessments, protests, complaints... Controversy and delays have also caused expropriations. In Romania, 42.6 hectares of land had to be expropriated for the works related to the bridge, with 242 entries in the land register, belonging to the Calafat Local Council, Romsilva and private individuals, but the scams by which the category of use of some land was changed from a lower to a higher category meant that the amount initially earmarked for compensation was not sufficient and the matter was postponed because of the 2008 legislative elections.

There was also controversy over the financial aspects - the construction of the bridge cost tens of millions of euros more than initially estimated and the completion date was postponed from 2010 to the end of 2013. Additional geological studies were needed due to a severe situation that had not been taken into account initially, leading to changes in the project, delays and additional sums. As the bridge was co-financed by ISPA pre-accession funds, the validity of this funding would have expired at the end of 2010 and the Bulgarian government asked the European Commission to extend the term of the Memorandum. In 2010, Prime Ministers Emil Boc and Boiko Borisov said in Sofia that they would team up to convince the European Union not to block EU funds for the project - without any certainty that the construction works would be completed on time.

In the summer of 2009, work on the rail infrastructure stopped because of houses illegally built on the route. Romania has not resolved the rehabilitation of the rail and road link between Calafat and Craiova. The booming ferry business on both sides of the Danube prompted a Bulgarian newspaper to exclaim: "Danube Bridge 2 has more enemies than friends".

According to estimates in the Financing Memorandum, by 2030 the bridge was to be crossed by 8,400 vehicles and 30 trains per day, and Bulgaria's Ministry of Transport estimated that traffic could reach 100,000 vehicles in the first year of operation. In reality, 508 294 vehicles crossed the bridge in its first year of operation.

The bridge officially opened on June 14, 2013 and was named "New Europe". The first vehicles crossed the bridge after midnight on June 15, 2013.

In 2022, a deal was signed between Romania and Bulgaria on a new Giurgiu-Ruse bridge that would be completed by 2030. If the Romanians could...

NOTES

1 The Stability Pact for South-Eastern Europe(SPSEE) was an institution, created after the escalation of the Kosovo war, aimed at strengthening peace, democracy, human rights and the economy in the countries of South-Eastern Europe from 1999 to 2008.

2 The bridge of Apollodorus of Damascus in Drobeta was 1,135 meters long, 18 meters high and 12 meters wide, with 20 pillars made of hard materials (stone, brick, mixed with lime mortar, clad with limestone blocks) built in the Danube (12 survived), supporting an oak wood superstructure that was destroyed and rebuilt several times. At the ends, the bridge was pierced by monumental gates. The Danube was partly diverted in order to build these piers, after which a series of caissons or cofferdams (made of wooden beams) were built in the dry riverbed, inside which the bridge piers were built.

3 The Giurgiu-Ruse "Friendship Bridge" was designed by Eng. V. Andreev, it is 2.8 km long, two-lane road bridge, bridge for railway traffic, sidewalks for pedestrians. The 85 m long central section is movable and can be raised to allow larger ships to pass. Construction took two and a half years.

4 The Pan-European Transport Corridors in Central and Eastern Europe as transport routes had been agreed in 1994 in Crete at the 2nd Pan-European Conference. Subsequently, the 1997 Helsinki Conference complemented the 1994 decisions and mapped out the 10th Pan-European Transport Corridor, valid after the end of the wars in former Yugoslavia

5 The Calafat-Vidin Bridge rests at its ends on three keys, two on the Bulgarian side and one on the Romanian side. Twelve piers are located between the piers, four of which are located in the navigable channel of the Danube, with an opening of 180 m to allow the movement of large tonnage river vessels. The quays and piers are founded on drilled piles. The bridge and passage decks are made of large precast prestressed concrete beams. On the bridge itself, the beams were installed using the beam launcher. The "camel-back" technology used is state-of-the-art, saves construction materials and ensures high seismic resistance. The bridge is unique in the EU but extremely popular in Japan, cheaper than any other technology.

-topaz-denoise-enhance-sharpen--15883-m.jpg)