Peripheries of the Danube

© Anca Galiceanu

Decline and potential

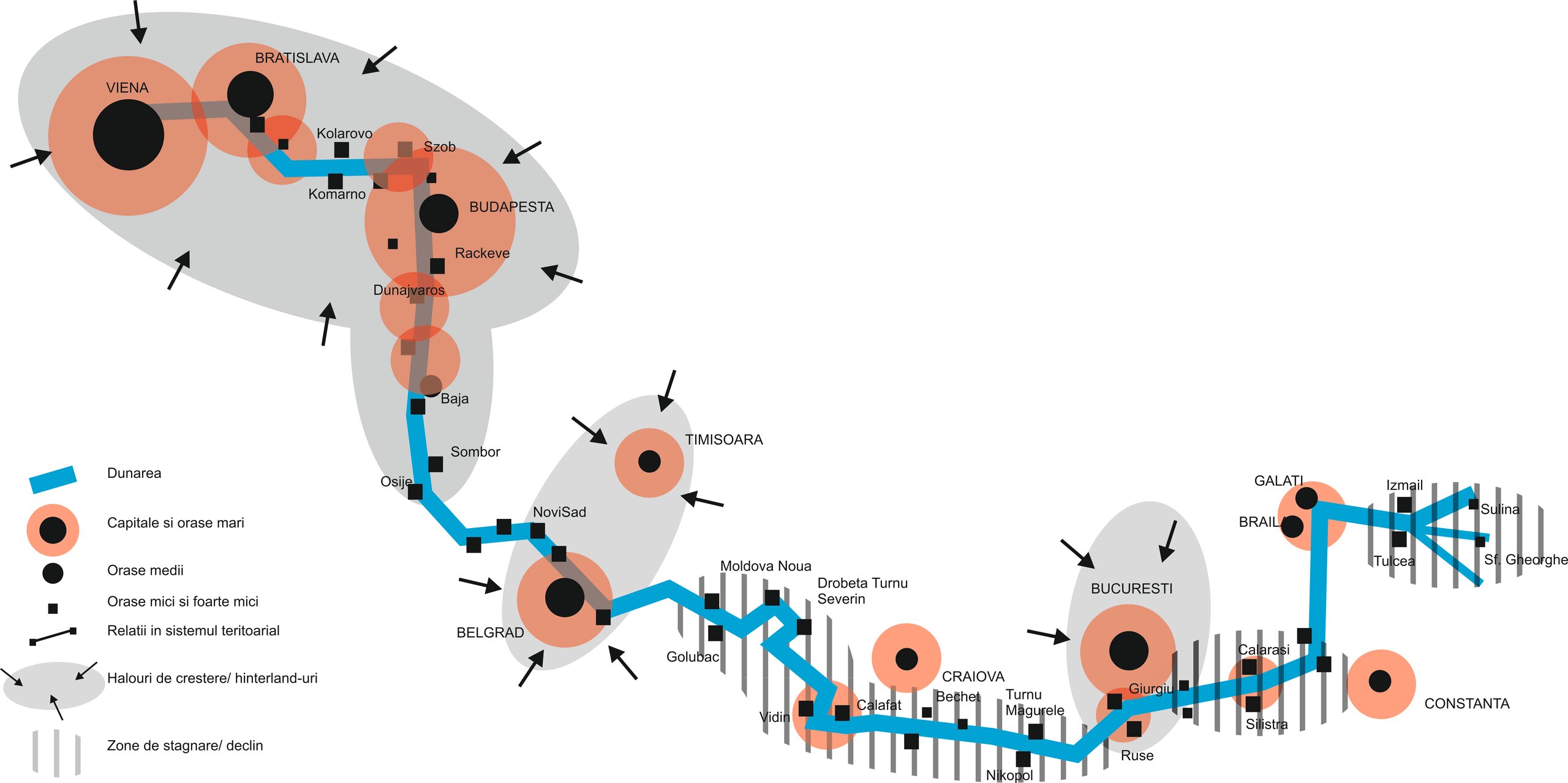

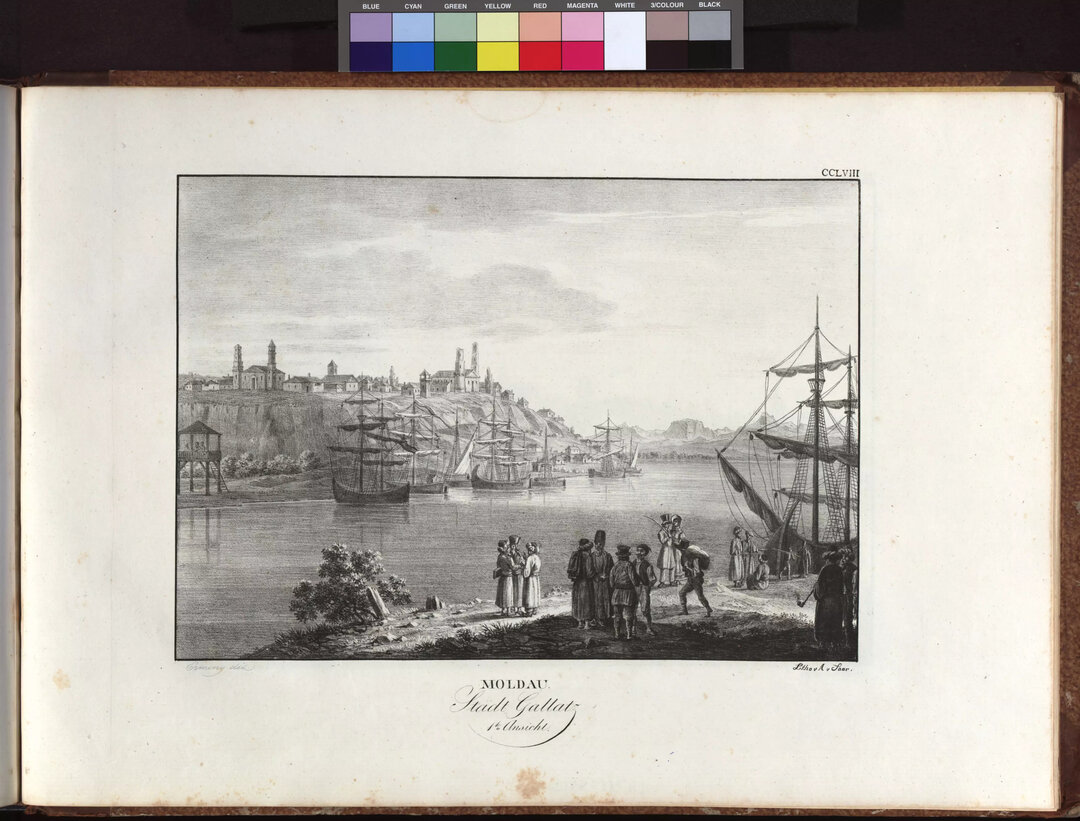

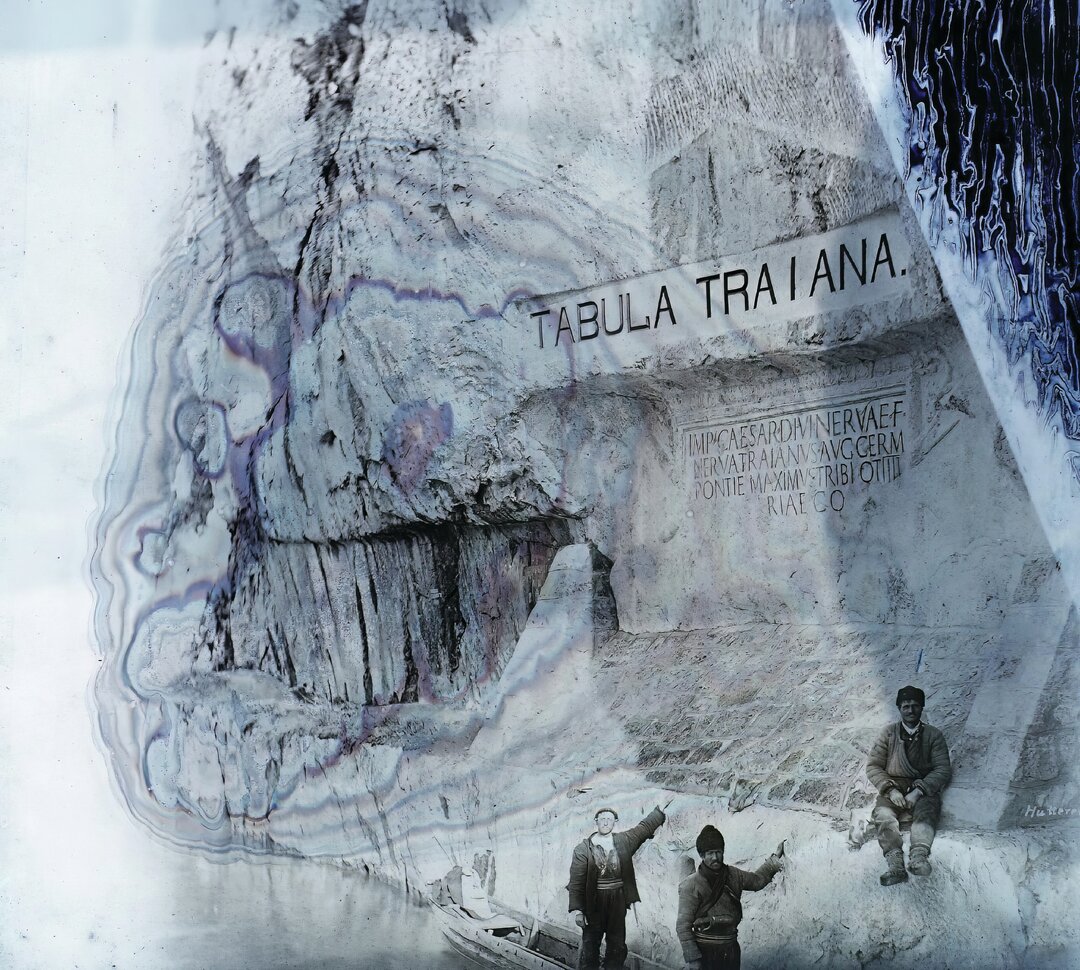

From the outset, the Danube Region raises a reflection on identity, all the more so as it is evident that it possesses as many identities as there are communities inhabiting it. Numerous research projects, some with European funding, take up this idea in their analyses at various levels. In recent projects1 aimed at discovering and promoting a Danube brand, the Danube has been approached and highlighted under a single brand, the Danube as a river-matrix of Europe, bearer of solid and sustainable identity values in historical, geographical, cultural, economic and eco-systemic terms. The vision also refers to a Danube able to link and unite people (over 81 million), communities and civilizations, encouraging communication and debate, inspiring development and creativity, opening a necessary dialogue on education at all levels, to make people understand and appreciate this river in all its facets and challenges. The ambitious objectives of these recently completed projects have materialized in the establishment of a multi-faceted European regional network, oriented towards interdisciplinary research and education, linked to the possibility of exploiting the still hidden values of the Danube cities - most of them, except for the capitals, in demographic, economic and social decline - for tourism.

For global tourism, the Danube is, first and foremost, a river of the great capitals, although they do not in themselves form a single destination, nor do they communicate the idea of common Danube values to the extent that the Danube's area is significant for Europe. Even cruises on the Danube, the only tourism products that address the Danube as a whole, are not the result of a common vision or strategy, but operate only through regional, isolated business models, contributing insignificantly to the economic and cultural cohesion of the Danube region (DANUrB, 2017). Moreover, current tourism practices and models in relation to the Danube region, even when successful, emphasize the same discrepancies that we can observe both in territorial systems plans and statistics: between the major poles of attractiveness that have created their own areas of expansion, growing and developing metropolitan, the rest of the localities, which are not in these halos of growth and influence, remain in a peripheral situation, with little chance of recovery. Neither their geographical position in the Danube system, nor their cultural and historical heritage, nor even their outstanding heritage features are sufficient to 'overturn' the marginal, discrepant and unsustainable character they attest to. In small towns, cultural heritage features cannot contribute to the socio-economic development they most need, because the value of cultural assets (local landscape, urban morphological values, architectural heritage, etc.) is rarely understood and recognized. The lack of a broad vision to safeguard and manage the values of local identity (belonging to a common heritage that has acquired specific characteristics over time, with traces of great national or regional histories or even the socialist past of some) means that these values are ignored as resources of the local economy without being included in a tourist circuit.

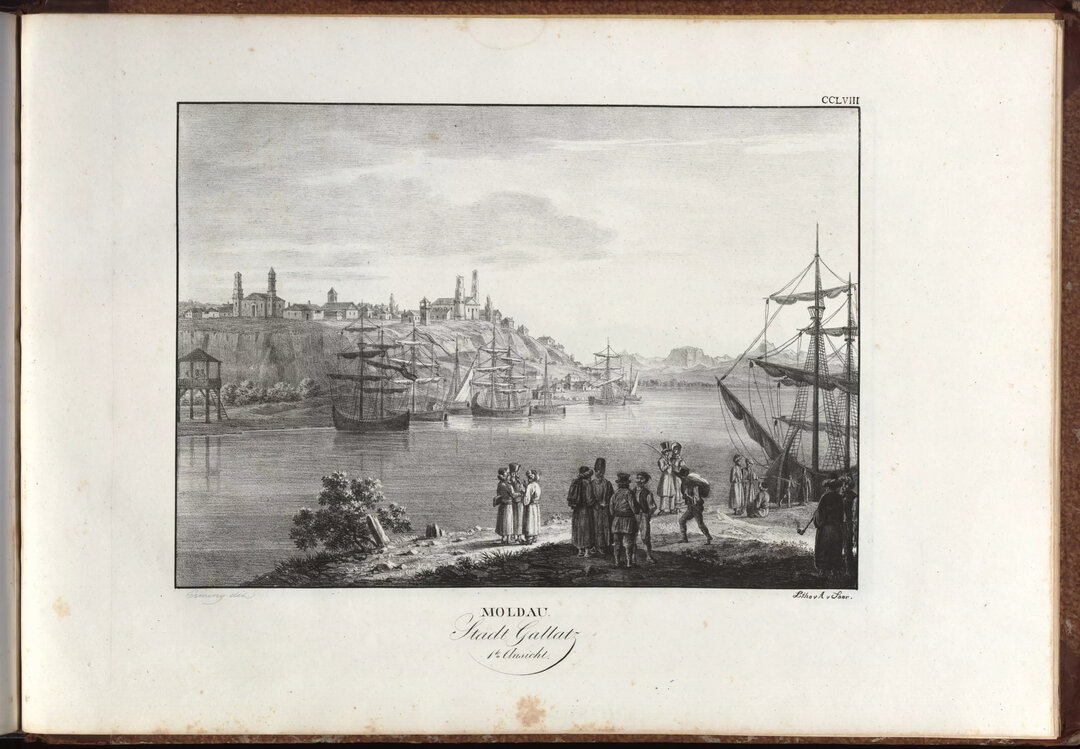

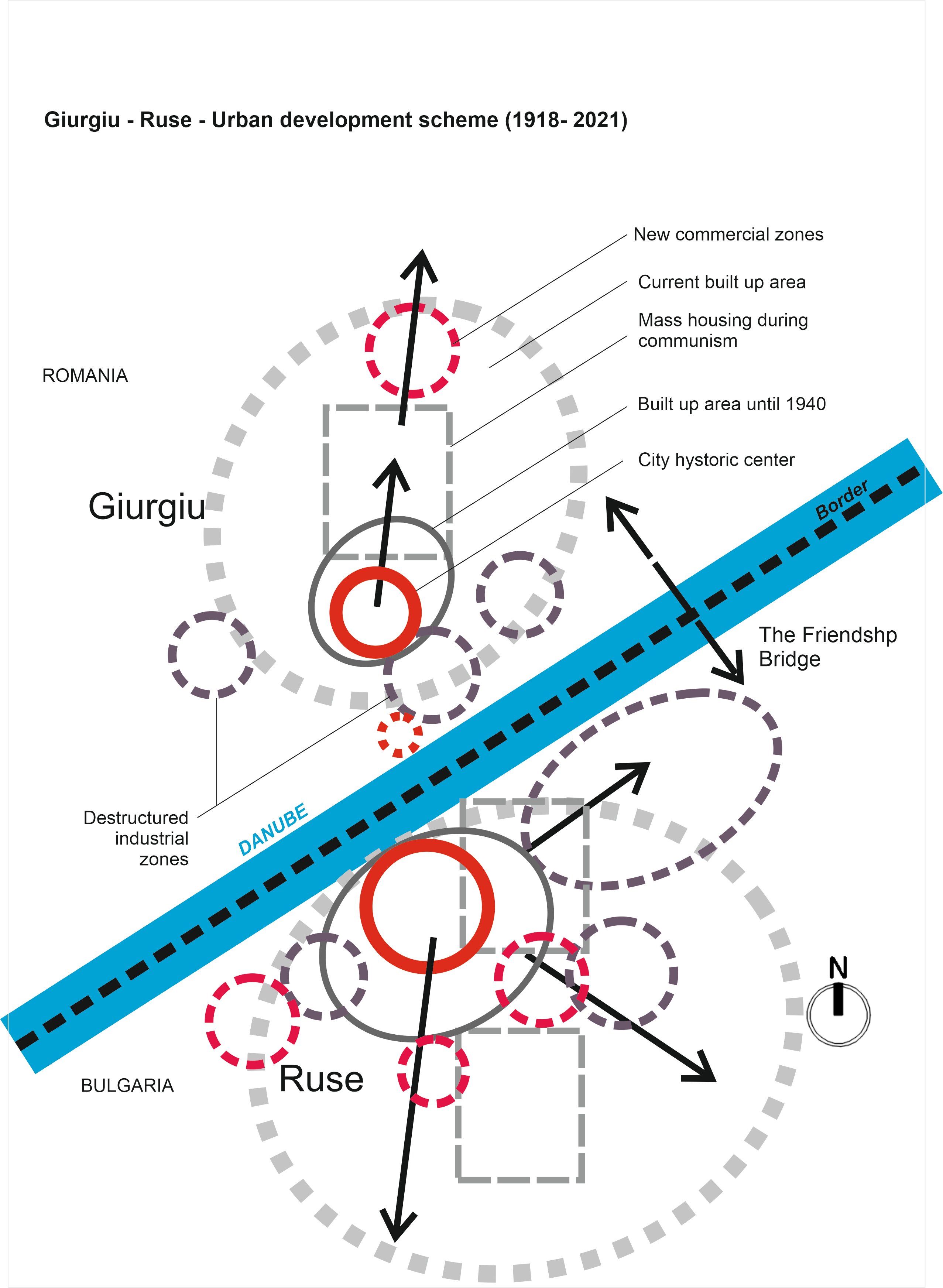

As a way of approach, the projects to which I have referred have made a coherent reading of the Danube region, of the similarities, differences and relations between local cultural values and the contemporary needs of the owner communities, imagining possible ways to make them visible, first at local level, so that they can then be integrated into a Danube network. This has the potential to create a positive impact on the consolidation of identity, similar to the situation when the coming together of family members (re)creates the spirit of the family as a whole, in a support and continuity on the basis of which a future can be projected. Thus, starting from the metaphor of the Danube network, the DANUrB and DANUBIAN_SMCs projects have developed a new narrative: that of a new and much more fluid connectivity, both along the Danube, trans-river and, especially, trans-border. A connectivity imbued with the European character in all the "capillaries" of this unevenly developed territory, having as starting points either single towns located along the river, such as Tulcea, Pancevo, Sremski Karlovci, Sombor, Baja, or towns twinned by neighborhood, such as Calarasi and Silistra, Giurgiu and Ruse, Sturovo and Esztergom or Komarno and Komarom; these are just some of the localities in whose territory still unknown values can be discovered...

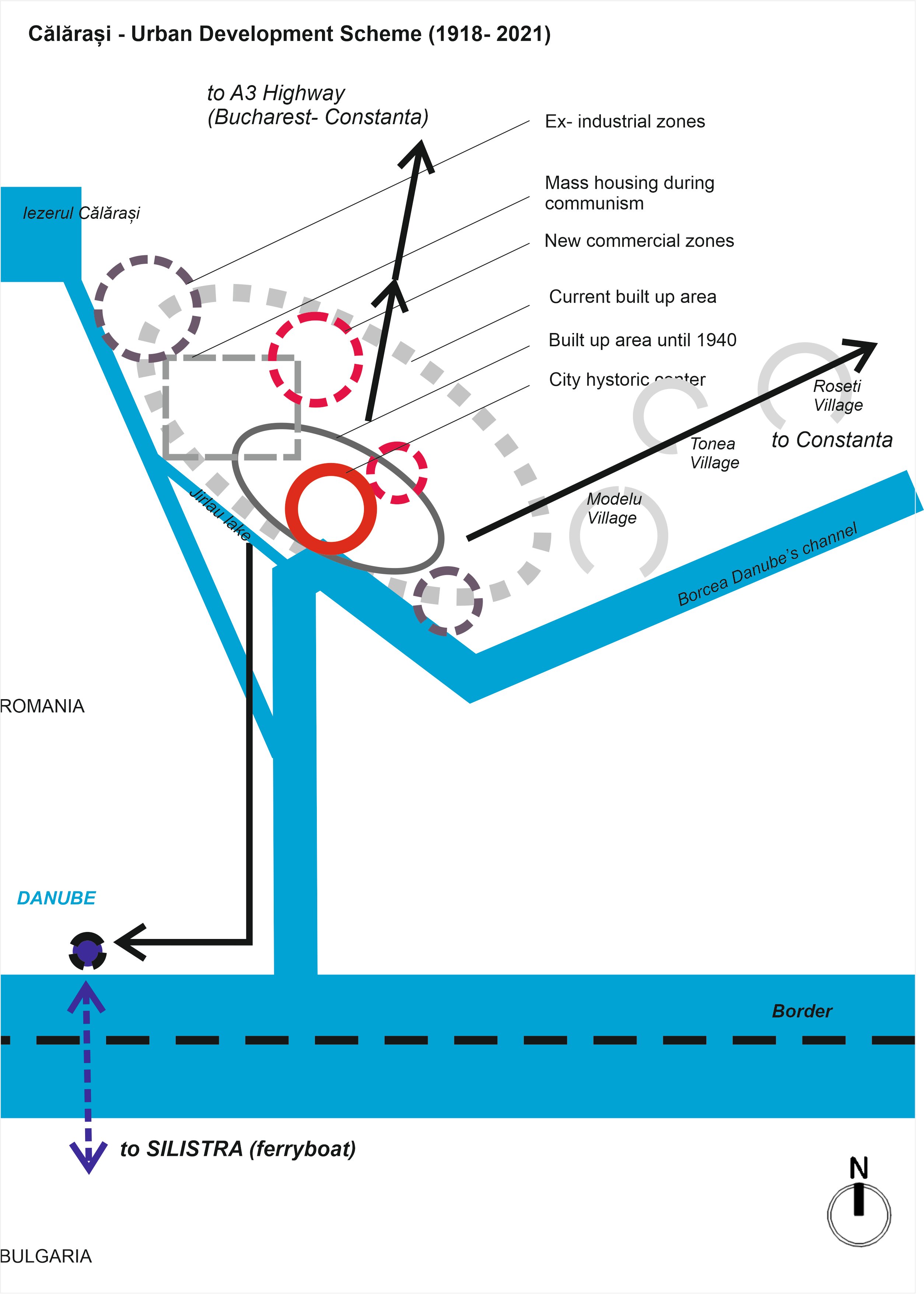

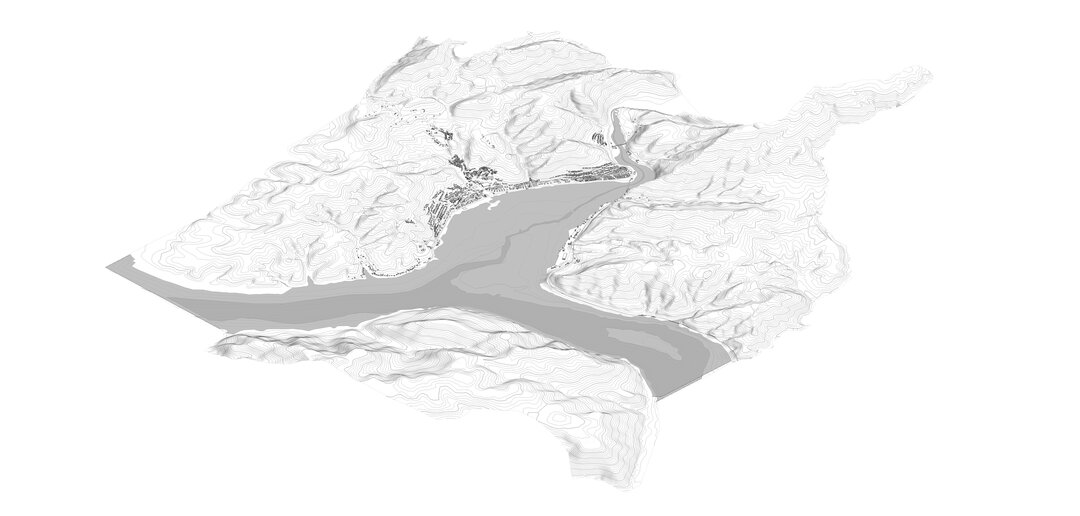

The peripheries of the Danube are visible in both spatial and social contexts, on a regional scale, through border towns, towns or peripheral regions quasi-isolated in the spatial-territorial systems, but also on a local scale, through peripheries generated by breaks in the fabric, by disruptive boundaries in relation to a context of a certain homogeneity of former industrial areas now abandoned. In any case, the peripheries of the Danube should be approached not as undesirable edges of the city, neglected and negligible, hidden from the gaze of tourists, but as part of a heritage that is insufficiently recognized, as a resource - both spatial and human - with huge potential for development. Topologically, the paradox of the Danube peripheries stems from the fact that they are often located right on the banks of the Danube, in the most natural proximity to the water, which is, in essence, the very origin, the generating center of the emergence and development of these localities and their umbilical link with their own history. Moreover, approaching these peripheries requires a change of perspective: to look at development from the perspective of decline and even centrality from the perspective of the margin; to look at the Danube from the source to the source and to put the magnifying glass on the gap between the developed areas, on the forms and patterns of decline in order to understand them, with a view to possible solutions.

The peripheral regions of the Danube are either border regions, whose peripheralization is caused by the position and functioning of the respective border in a certain historical context, or they are localities located at considerable distances from the large centres, influenced in particular by the drying up of resources, but not assimilated by them; a third cause is the sum of both situations. The current situation for the Middle and Lower Danube stretches shows that all the regions are peripheral, with a shrinking population and a high degree of isolation within the territorial system. In these regions, tourism is not an immediate option and is not promoted, being overshadowed by a multitude of pressing needs linked to quality of life. Against this backdrop, simply declaring rural tourism as an important springboard for their development is at best utopian: it cannot 'cure' or cure insufficiently recognized problems.

In order to understand the nature of these peripheries and the real chances of development, it is necessary to look more closely at the processes of spatial shrinkage, the patterns they follow, and the way in which the quality of places is being lost, not only as a result of demographic decline and emigration (statistically proven), but also of lack of interest, community apathy, mistrust, incompetence or abuse.

In urban planning, spatial patterns of city growth are well known, but patterns of shrinkage are less studied, perhaps also because progress/growth of cities more quickly leads to a generalizing discourse, validated by a long history, whereas decline or shrinkage are phenomena with certain particularities in the evolution of cities, specific to particular periods and local or regional contexts. Starting from the definition given by the Cities International Research Network (Oswalt, Rienitz, 2006), which states that a shrinking city is characterized, on the one hand, by a significant population loss (more than 0.15% per year for at least 5 consecutive years) and, on the other hand, by an economic transformation with some symptoms of structural crisis, we have observed that in the Danube region, the massive discrepancies between the North-West and the South-East make it difficult to apply this "rule" to all cities of the same size. Assuming that population loss is a direct consequence of deindustrialization and that the structure of the main administrative, geo-political and economic boundaries on the European territory already induces a centre-periphery relationship on a macro scale, three main categories of shrinking cities in the Danube area can be distinguished.

Naturally shrinking cities, those which, following the "industrialization boom", had an unnatural leap in growth during the years of socialism and which, after 1990, against the background of structural changes in the economy and, often, in the functional profile, began to depopulate, turning, instinctively, not very certainly, towards services, trade, agriculture. In terms of the macro-temporal evolution of these cities, we could even speak of a return to normality. These cities still have sufficient intrinsic resources for rebuilding, they have a strong identity thanks to their pre-communist history and they have the prerequisites to become emerging cities or regional micro-centers and to develop positively through better planning.

Cities in risky decline - former mono-industrial cities, or new cities, created exclusively on the socialist logic of territorial development, without a historically validated identity and steadily losing population as the industrial engine disappears. Here, recovery seems to be more difficult, requiring a real "reinvention", an integrated, multi-systemic treatment, as in a chronic disease (Haase et al. 2013).

False shrinking cities, in fact, cities in socio-economic stagnation, with statistically noticeable demographic decline, but nevertheless insignificant in the sense of the definition of "shrinking cities", with an ageing population, closely linked to a traditional way of life. For these cities, adapting and resettling in the current urban system means change and they need creative and participatory planning, which means reinventing from within and can only go at the pace that the inhabitants can sustain.

This typology characterizes urban contraction in its global data, without taking into account the dynamics at the micro-spatial scale (Martinez-Fernandez, 2012) and the specific-local responses that can nuance a process of this kind.

From another point of view, of how contraction manifests itself at the internal spatial level, in the urban structure, through the 'footprints' it leaves in the urban fabric, two major situations are visible, occurring both distinctly and simultaneously:

Contraction through de-structuring, as a result of the partial or total loss of the production function, and which is often correlated with a loss of urban identity, entailing an amplified effect of peripheralization, perceptible in the urban landscape through the image of decayed, degraded or abandoned spaces;

Contraction through de-connection, when it is mainly due to the change of centralities in the gravitational field of the urban system, and this leads to a decrease or even loss of internal connectivity and accessibility, to deficiencies in the relationship between areas and neighborhoods generating multiple dysfunctions as a result of which the city becomes unattractive, entering a spiral of demographic loss.

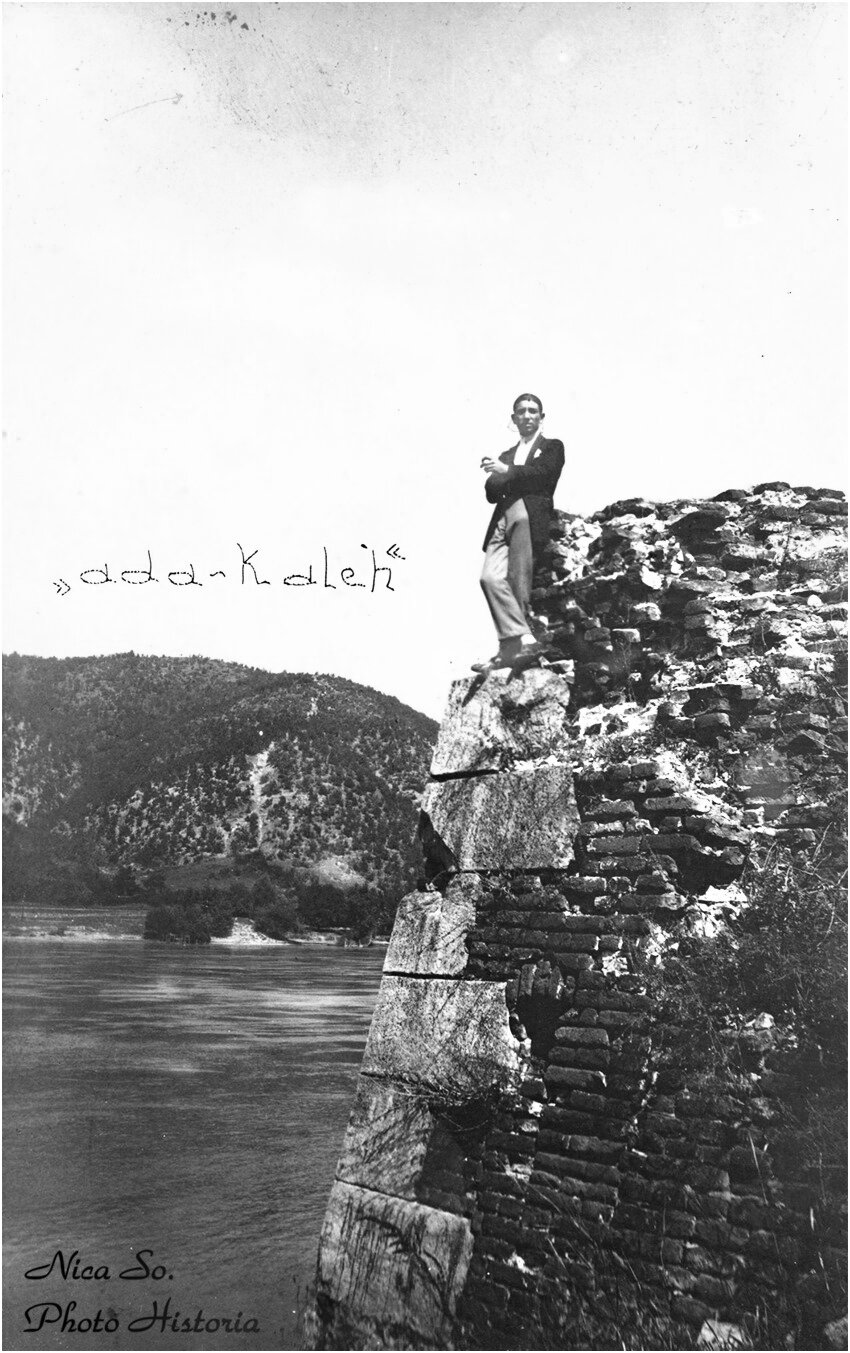

Beyond maps and typological classifications, researching the Danube peripheries also means discovering a discrete treasure trove of values, apparently from another register of development, values that we often have to admit that it is precisely the isolation, the disconnection of these localities from the system of major consumers and the decline in economic activities that have made it possible to preserve or (re)emerge a specific distinct character, rural-natural, quiet/'slow', where we can find local products, authentic crafts and traditions that are still alive, all of which are valuable for a good quality of life and for a specific type of tourism, with a strong identity, connected and accessible in a special area, the Danube; a tourism that can appreciate and maintain/ protect these values, often opposed to mass/global and globalized tourism.

In the framework of the projects mentioned at the beginning of this article, the idea of "livability" in peripheral cities has been analyzed and tested, and several series of projects have been developed together with students and teachers from the universities involved, oriented either towards the sensorial mapping of significant places, either on the understanding of the need for quality public space and inclusive accessibility, or on the possibilities of synergistic, acupuncture action in the "neuralgic" places of the city, or on the possibilities of the public, planted space to be (re)integrated into the social-urban environment through various functional options, including leisure.

Optimistically, more often than not, in these exercises, and especially for young people, the decline turned out to be not an end, a dead-point, but, on the contrary, a turning point, from which something new and qualitatively superior can begin. The good practices identified and studied locally have shown that peripherality is not always a prerequisite for failure, but can become a hallmark of development, and awareness of this at all levels of urban life, including local government, could positively affect the current trend of economic decline in these localities.

NOTE

1 We refer to the DANUrB (2017-2019) and DANUrB+ (2020-2022) projects carried out through the international INTERREG - Danube program and the Erasmus + DANUBIAN_SMCS (Creative Danube: innovative teaching for inclusive development in small and medium-sized Danubian cities) project, coordinated by international consortia of which the University of Architecture and Urbanism "Ion Mincu" of Bucharest was also part.

References:

Djukić, A., Kadar, B. Stan, A., Antonić, B. (Eds.) 2022. D+ Atlas: Atlas of Hidden Urban Values along the Danube, Belgrad University

Martinez-Fernandez, C., Audirac, I, Fol, S., Cunningham-Sabot, E., Shrinking Cities: Urban Challenges of Globalization, in International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, Volume 36.2 March 2012 213-25

Cârlig, I., & Raica, M. (2019). Post Industrial Stories. In Ilinca paun Constantinescu (ed.) Shrinking Cities in Romania (pp. 381-382), Editura MNAC.

Shürmann, C., & Talaat, A. (2003) Towards a European Peripherality index. In D. Kidner, G. Higgs, & S. White (Eds.), Socio-economic application of Geographic Information Science (pp. 255-266). London: Taylor and Francis.

Robinson, J. (2006): Ordinary cities: Between Modernity and Development. Routledge, London. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research (2012) Symposium on shrinking cities, March, 36, 2, 213-414.

Haase, A., Bernt, M., Grossmann, K., Mykhnenko, V., Rink, D. (2013): Varieties of shrinkage in European cities, In: European Urban and Regional Studies, (DOI: 10.1177/0969776413481985, in press).

Oswalt, P, Rienitz, T. (ed.) 2006. Atlas of shrinking cities, Hatje Crantz, Ostfildern.

Nagy, E. (2013). Factorial analysis of the territorial disparities on the southern part of the Romanian - Hungarian border. Forum Geografic, XII(2), 125-131. doi:10.5775/fg.2067-4635.2013.148.d.

Duvillard S., (2003), "Which relevant scales and methods for the observation of segregation processes? Déplacer le point de perspective de la grande ville à la petite ville, de la société à l'individu?", Communication au XXXIXème colloque de l'ASRDLF, Lyon, September 2-3, 2003.

Popescu C., Soaita, A-M., Persu M-R.(2020). Peripherality: Mapping the fractal spatiality of peripheralization in the Danube region of Romania, in Habitat International107(2021)102306

Hollander, J. B., Pallagst, K. Schwarz, T., Popper, F. (2009) Planning Shrinking Cities, Progress in Planning, Volume 72, Issue 3.

Grədinaru, S. R., Iojə, C. I., Onose, D. A., Gavrilidis, A. A., Pətru-Stupariu, I., Kienast, F., & Hersperger, A. M. (2015). Land abandonment as a precursor of built-up development at the sprawling periphery of former socialist cities. Ecological Indicators, 57, 305-313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2015.05.009 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2015.05.009

Humphris, I., & Rauws, W. (2021). Edgelands of practice: post-industrial landscapes and the conditions of informal spatial appropriation. Landscape Research, 46(5), 589-604. https://doi.org/10.1080/01426397.2020.1850663 https://doi.org/10.1080/01426397.2020.1850663

Stan, A.2018.'River as center and/or barrier. The peripheral urban landscapes of romanian danube cities" in Journal of Urban and Landscape Planning - JULP no.3/2018. pp.69-76

-topaz-denoise-enhance-sharpen--15883-m.jpg)