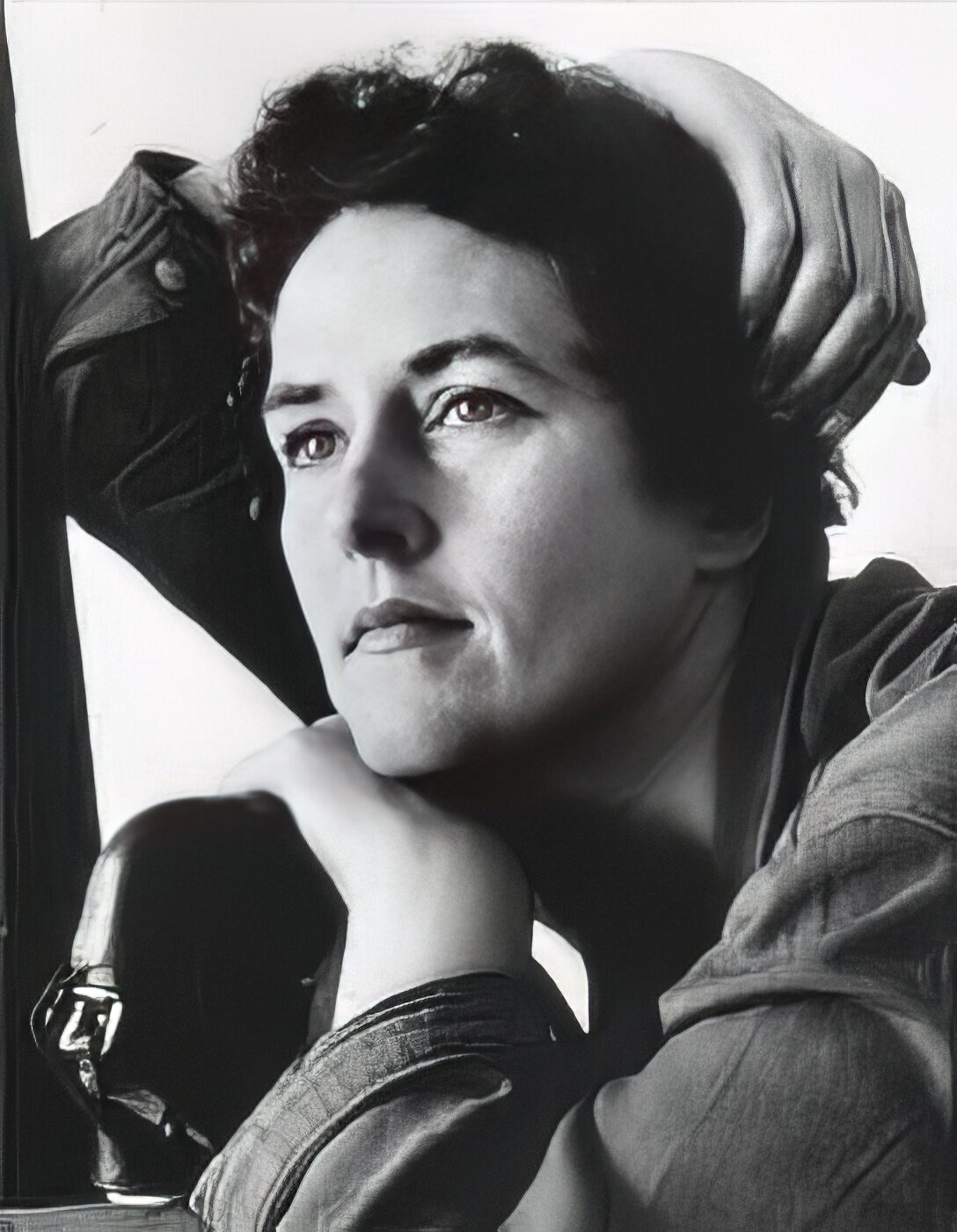

Inge Morath's Danube

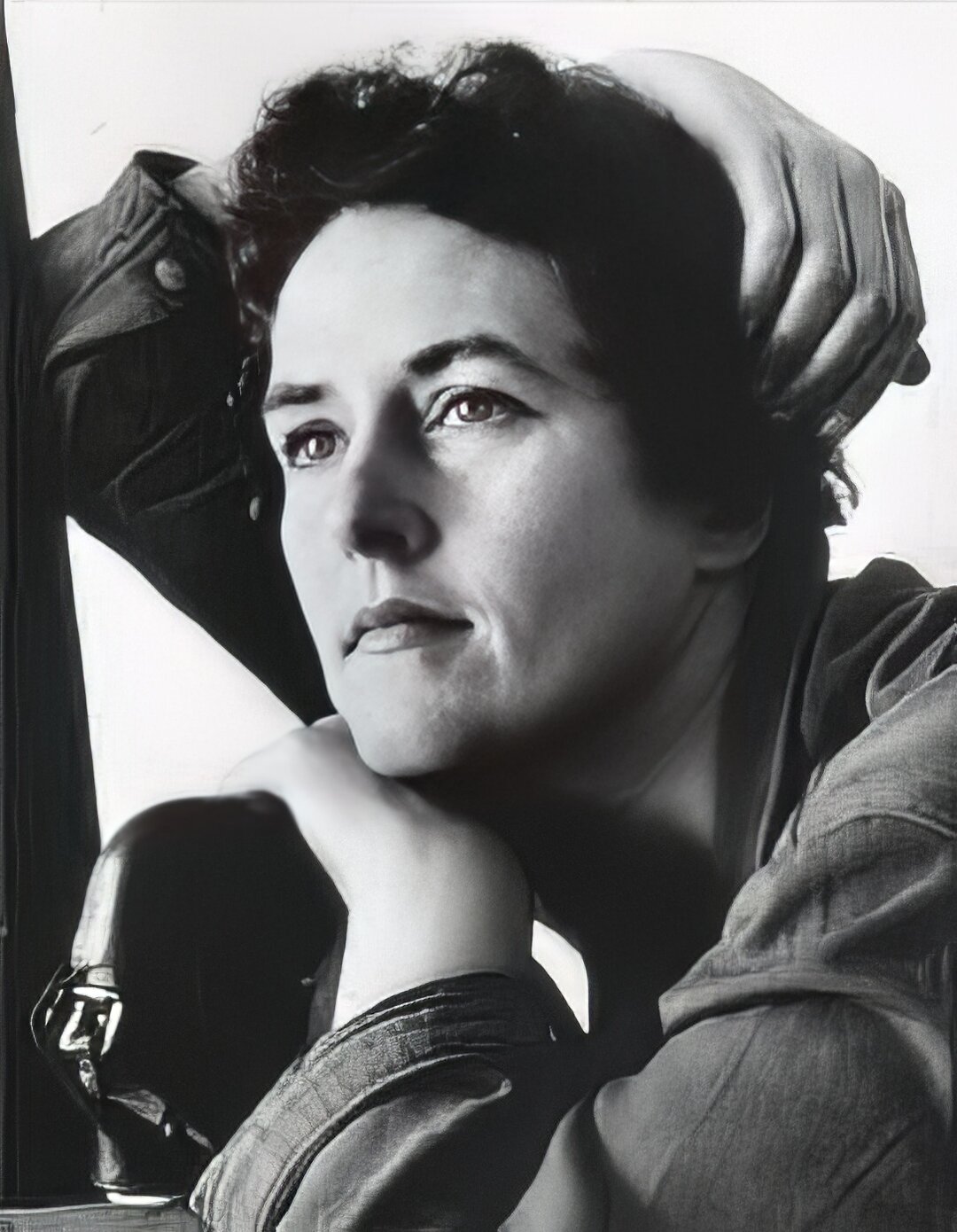

Inge Morath © Inge Morath

Half a life on film

Photography is a strange phenomenon. Despite the use of that technical tool, the camera, no two photographers come back with the same pictures, even if they were in the same place at the same time. The personal vision is usually present from the very beginning; the result of a special chemistry between background and feeling, traditions and their rejection, sensitivity and voyeurism. You trust your eyes and you can't help but bare your soul. Everyone's vision necessarily finds the right form to express itself.

Inge Morath (Life as a Photographer, 1999)

Researched by Inge Morath, Central Europe (Mitteleuropa) and Eastern Europe have retained certain enduring characteristics and uniqueness from the rest of Europe and the world, despite having undergone natural changes over time, through industrialization and prosperity, undergoing the dynamics of political divisions and revolutions along with all the related transformations in the culture and daily life of the inhabitants.

Inge Morath had to become a photographer. Life pushed her in that direction, decided for her. After completing her studies in linguistics at the University of Vienna, she worked for several years as a translator and journalist, and later as an editor for the intelligence service of the US armed forces in Salzburg and Vienna. When she started writing for the Wiener Illustrierte Zeitung, she was asked to supplement her articles with photographs, which forced her to cultivate an interest in this field of art, especially photojournalism. Her main sources of information and inspiration were the illustrated magazine Life and photo albums. Around the same time, in 1951, he received his first camera as a Christmas present. A little later, he met and worked with photographers such as Lothar Rübelt, Franz Hubmann and Erich Lessing, and later as editor of the Austrian version of Heute magazine, he collaborated with the outstanding Austrian photojournalist Ernst Haas. The editor of Heute, Warren Trabant, sent several articles written and illustrated by Morath to Robert Capa, one of the founders of the Magnum agency in Paris, the first organization of independent photographers, which is now a major press agency. Shortly afterwards, in 1953, Inge went to Paris and began working with Henri Cartier-Bresson, George Rodger and David Seymour, doing documentary and preparatory work. In her memoirs half a century later, she said: 'It was there that I learned the most'. These were probably not just his subjective impressions, since he became one of the best photojournalists of the time and got to know the secrets of photography in the city that remained the capital of the art for several decades.

One could say that Morath was self-taught, but that would not be entirely true. She made active use of meeting exceptional photographers, following their work, being inspired by them, analyzing their way of looking at and depicting the world. At the same time, she started taking photographs with an old Leica - a fast, precise camera with excellent optics, considered perfect for street photography. In 1955, after returning to Paris from London, where she had lived with her first husband, Morath took a series of photographs depicting politically involved priests. The series caught the interest of Capa who, after seeing other works by the young photographer, decided to take her on at Magnum. She and Eve Arnold were the first women to work for the agency. Apart from Inge's undeniable photographic talent, Capa also appreciated Inge's fluent communication in several languages, her openness and ambition. Thanks to his trust, a lifelong adventure for Morath, spanning several decades, began. An adventure with travels, photography in various parts of the world, portraits, commissions from the world of industry, fashion, film and theater.

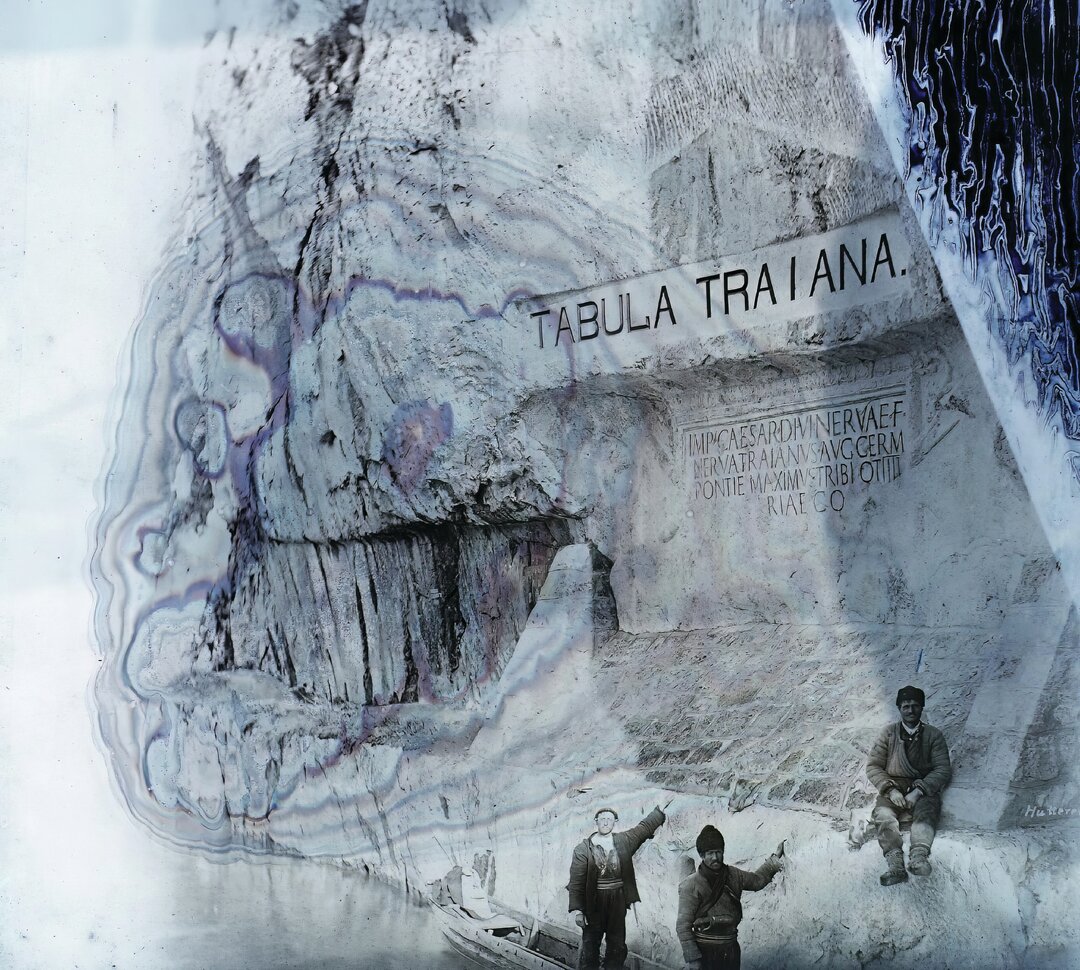

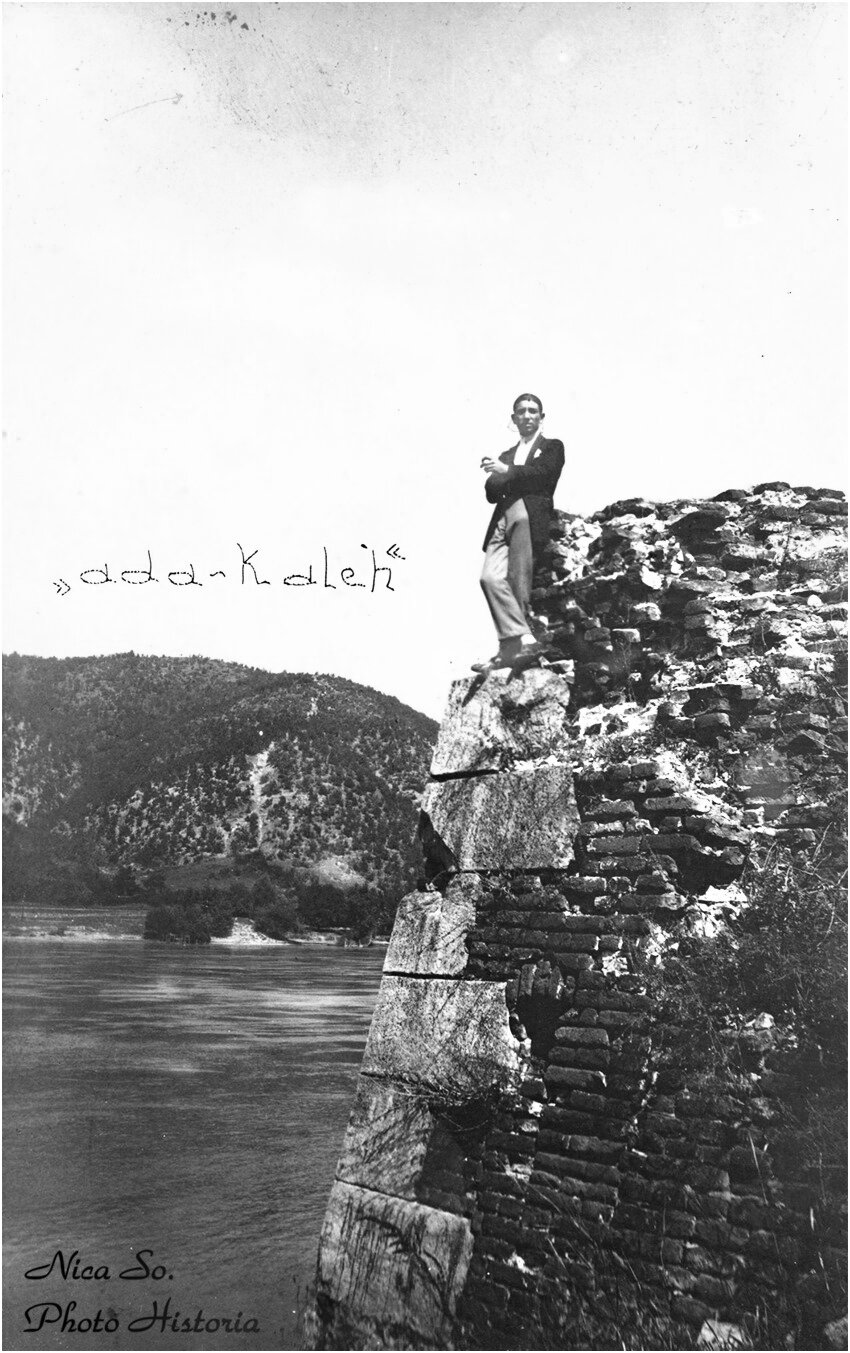

In 1958, the photographer started the Danube project. The idea was to study the varied and complex culture of Central and Eastern Europe. The choice of the Danube as the core of the project was no coincidence. Europe's second longest river flows through eight countries with different languages, cultures and religions. This feature of the Danube and its potential had been recognized and exploited since antiquity, and found its full expression in Claudio Magris's 1986 essay. Both in Magris' essay and in Morath's works, the Danube is a pretext for telling the story of Mitteleurope. One critic has pointed out that Morath's fascination with the river was rooted in his natural inclinations towards a cursicity of life, frequent moves and working simultaneously on several levels and through different media. According to Austrian photographer Kurt Kaindl, Morath was motivated by a desire to show "the great cultural breadth of the East and of Europe. Since joining the Magnum agency, he has repeatedly photographed different parts of the Danube, especially in his native Austria and neighboring Germany".

In his diary, Morath noted the debut of the project in the following words: "A great adventure begins". On May 6, 1958, he wrote: "Leaving Paris at 9:20 p.m. by night train for Vienna. Orient Express. Or is it only called Orient Express outside Vienna?". Let's imagine Morath at that moment, a woman setting out on a solitary journey in the mid-20th century to a world where cultures, political systems and lifestyles were at odds with one another.

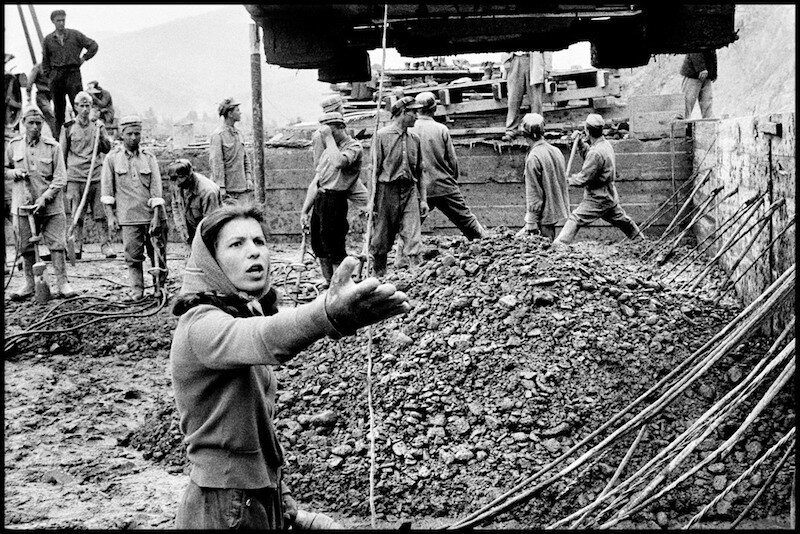

She constantly encountered concrete difficulties. He traveled "on foot, by car, by truck, by train, by ferry, by boat and by ship". Although he knew several languages and despite his calm manner in dealing with locals, he often faced bureaucratic obstacles. She needed special authorizations and permits to photograph public meetings, especially on the eastern side of the Iron Curtain, which she was not used to. In July 1958, she noted in her diary: "I am adamant. I finally got permission to take part in a parade commemorating the victory of communism. It is very hot. I'm still suffering from a kind of isolation".

Photographs from his first trip were published in 1959 by Paris Match, a French social and cultural magazine that was highly regarded, especially among the middle and upper middle classes, and was a style and career creator. Other trips followed, interspersed over time as they were squeezed in among Morath's other projects. The last trip came after the fall of the Iron Curtain in 1993, by which time she was already a permanent resident in the United States and a recognized photojournalist, but also a celebrity portrait photographer and wife of playwright Arthur Miller. She accepted a proposal from the curators of the Fotohof in Salzburg, Kurt Kaindl and Brigitte Blüm, to revisit with them the places she had photographed years before. While his solo expeditions along the Danube, which he usually financed out of his own resources, were purely personal and not part of an exhibition project, the aim of his latest trip was to lay the foundations for an exhibition and a book.

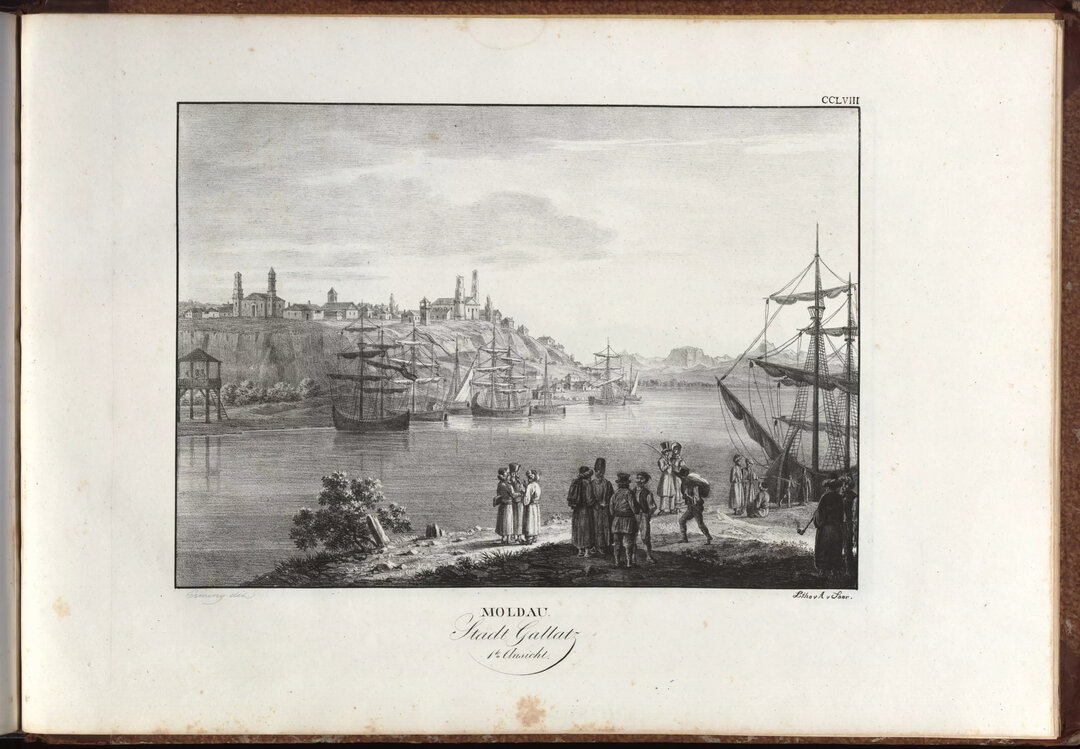

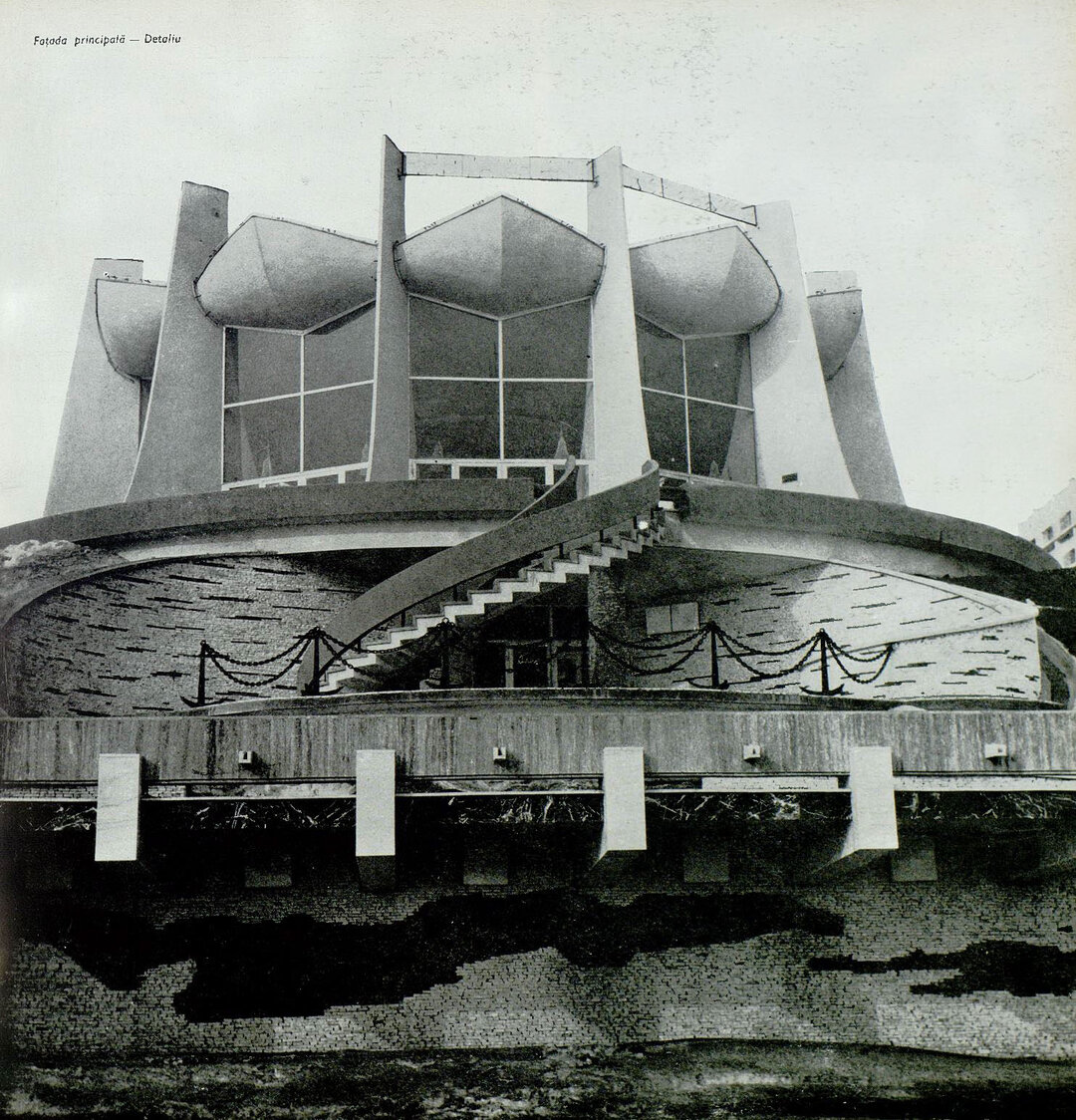

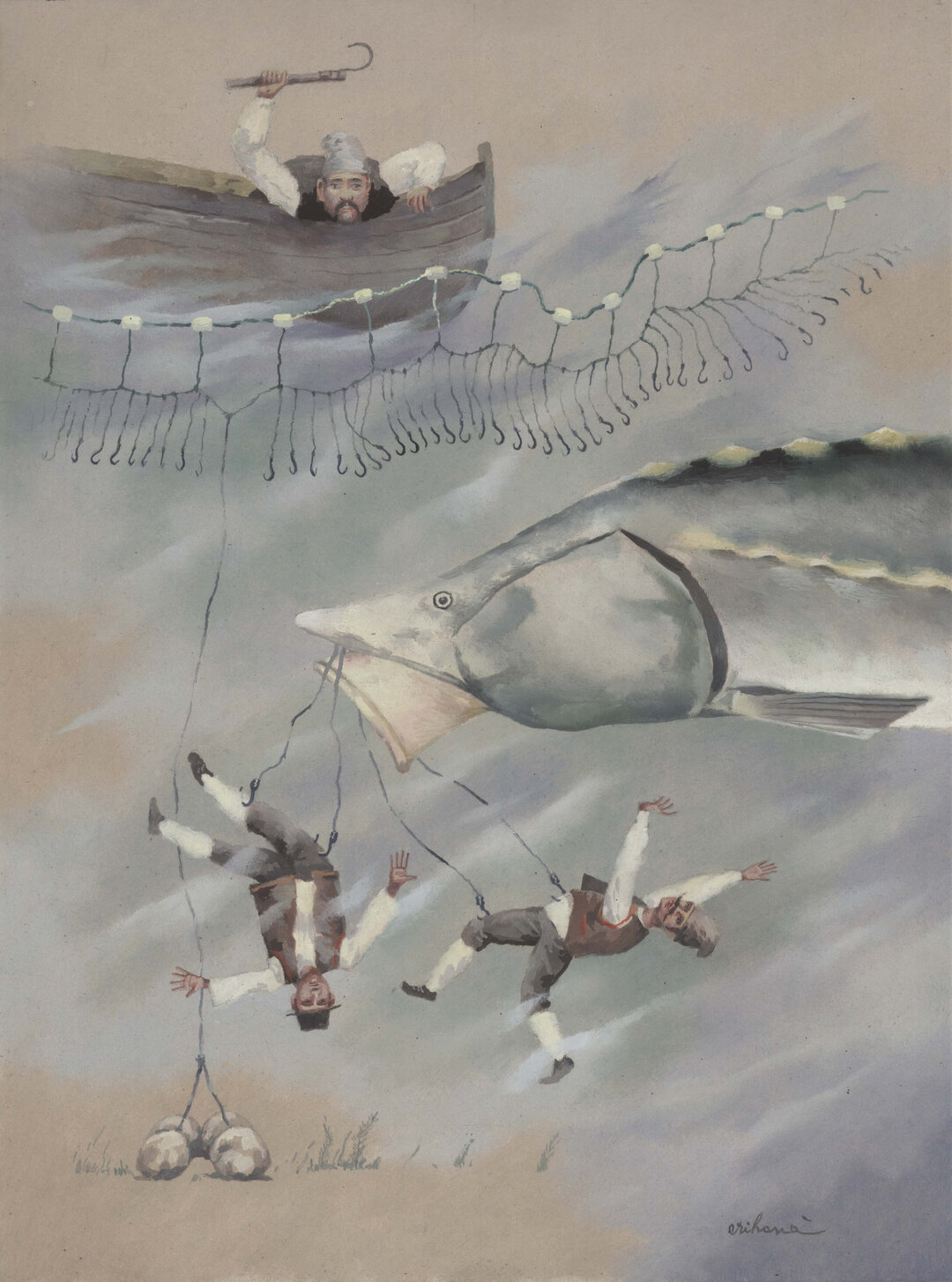

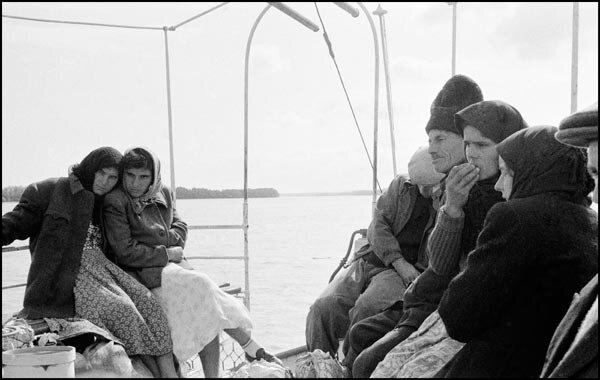

Morath's many trips resulted in several thousand photographs. Only a small fraction made it into the photographer's portfolio, books or exhibitions. They are a monumental testimony to the changing reality of Mitteleurope, and it was not just the borders or political systems that changed, but first and foremost the cultures, customs and landscapes. Photographs taken in Romania in the 1950s show a rustic society still recovering from the ravages of war. The black-and-white frames depict both a leisurely pace of life and the steadfastness of pre-war traditions. One photo shows three girls dressed in folk costumes, one of them wearing a crown on her head. The photo caption says they were going from house to house to announce an engagement to their neighbors. Behind them can be seen an ox-drawn cart preceded by a woman holding a pitchfork on her arm. Another photo taken around the same time shows passengers on a ferry crossing the Danube between Galati and Tulcea. The flowered skirts, the dark-colored banners, the women's headscarves and the men's top hats speak more of the isolated countryside and its problems than of the inhabitants of these regionally important towns.

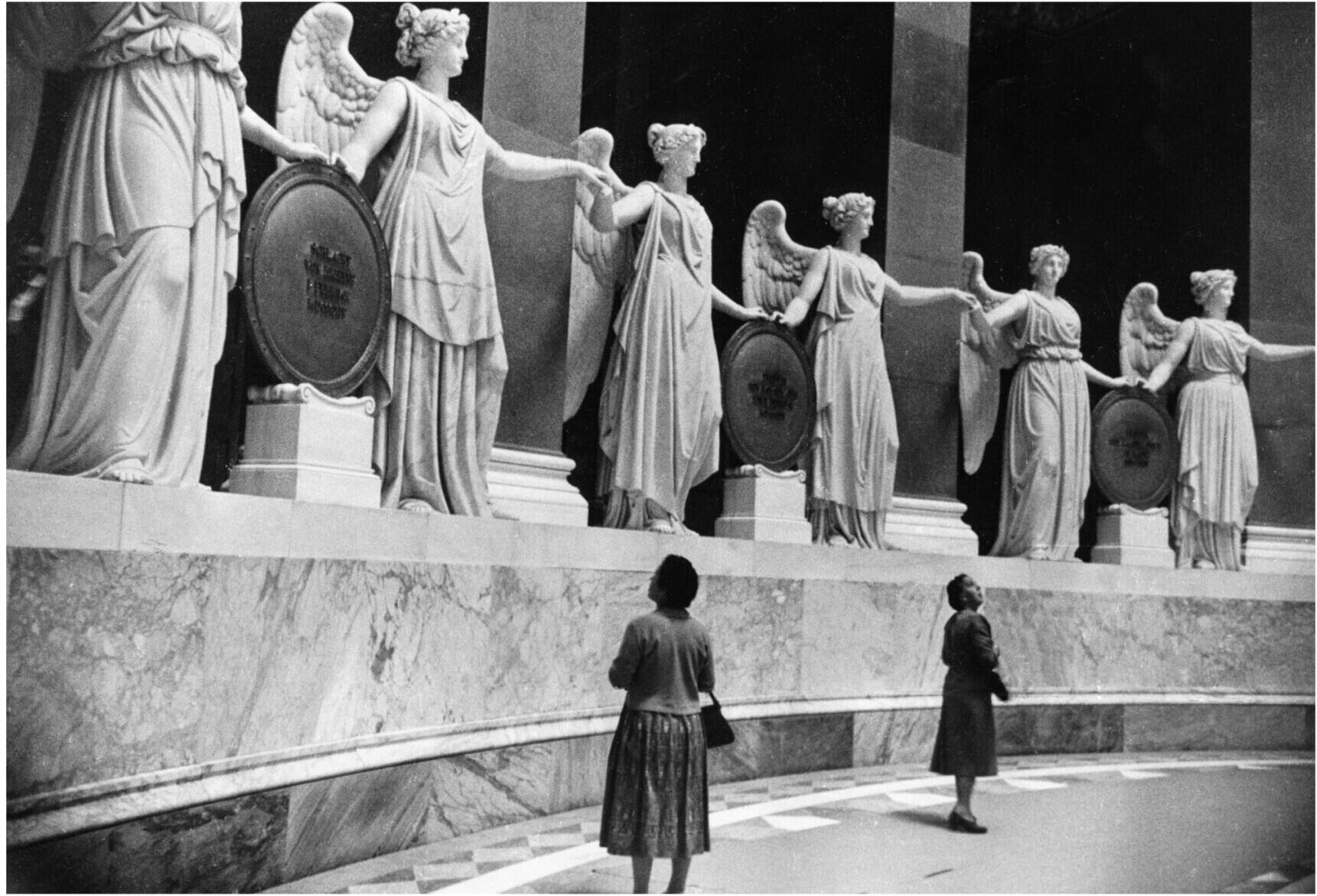

War was to be an important theme for Inge Morath in the Danube project. A photograph showing a fragment of a Gothic figure above the Ulm skyline and a fragment of a crenelated roof of Ulm Cathedral suggests a city where the medieval architecture of the historic center was almost entirely destroyed by an Allied air raid in 1944. And in the photograph taken 15 years later in Kelheim, showing the interior of the Hall of Liberation, two women can be seen gazing at the monumental sculptures symbolizing the German victories in the 1813-1815 war against Napoleon. The splendor of the figures and the atmosphere of ancient Greece contrasts with the rubble left behind by the Germans after the last war; a war to which Morath also fell victim. After surviving the Second World War in Berlin, the future photographer set out for her native Salzburg on foot, fleeing Soviet bombs. While working as a reporter for Magnum, she consistently refused to document military conflicts. Experiences of hunger, fear and the possibility of losing everything made her sensitive to beauty, as Morath and Arthur Miller's daughter Rebecca Morath emphasized: "I think her attitude toward beautiful objects actually came from the fact that she had nothing at the time," she wrote. The search for beauty - in the choice of subject matter, in the carefully grounded framing of harmonious, often symmetrical compositions, in the balanced and calm color scheme, in the melancholic mood of the images - is the unifying thread of the entire series. Sometimes the theme became beauty itself. In 1961, a series of photographs depicting the Concordia Ball was taken in Vienna. This annual event organized since 1863 was extremely prestigious and popular among the Austrian elite before the First World War. Eventually disbanded by the Nazis, it was revived after the war, but the first ball was not organized until the early 1960s. Morath's photos show couples dancing, ladies in white dresses, the splendid interiors of Vienna's city hall. They contrast sharply with photographs taken in Bulgaria and Romania at a similar time, but like them they are a metaphor for the triumph of life over death, joy over resignation, tradition over the destruction of culture caused by war. A similar message comes through in the views of the Prater, Austria's largest adventure park, or in the many portraits of anonymous people sitting in cafes, reading the papers or eating lunch.

The river itself often appears in photographs; as the main subject or sometimes in the background, on road signs, captured while traveling by boat or visible from far away on the horizon. It determines not only the geographical axis of the project, but also its ideological dimension. For there is nothing more constant in nature than a river because, although it sometimes changes course, it follows virtually the same path for centuries. At the same time, since antiquity, the river has been used as a metaphor for fickleness, as in Heraclitus' famous sayings. Studied by Inge Morath, Central and Eastern Europe have retained certain enduring characteristics and uniqueness in relation to the rest of Europe and the world, despite the fact that they have, over time, gone through natural changes, industrialization and prosperity, undergoing the dynamics of political divisions and revolutions along with all the related transformations in the culture and everyday life of the inhabitants. Inge Morath was not only a documentarist of these transformations and a eulogist of separation and diversity, but also of their materialization. She grew up in times of divisions and tensions, of transformations and reconstructions, when the Nazis came to power, and she completed the cycle, ending her rich and intense life in a memorable period for the development of European democracy - at the time of the territorial expansion of the European Union and, thus, of the improvement and consolidation of its position.

But the Danube project did not end with the photographer's last journey. In 2014, eight winners of the Inge Morath Prize, awarded by the foundation that bears her name, set out in the footsteps of the woman who inspired them. They were to travel for a month along the same route Morath followed for half her life and visit the places she immortalized. At the heart of the project was their belief that the protagonists of photo reportages usually don't get to see the results of the photographer's work - exhibitions, books or the photographs themselves. The photographs that made up the Danube series had been exhibited in many prestigious galleries, but had not reached most of the places and people they portrayed. Hence the idea of turning the project into a kind of traveling exhibition. In this way, Morath's works visited the places where they originated, reviving the collective memory of the communities living there. Seeing the photographs taken half a century ago allowed the protagonists to access their own history, as seen through the eyes of an outsider, and to integrate it into their collective imagination. They also had the opportunity to see their own culture in a broader chronological and territorial context, and thus to strengthen their European identity.

The whole initiative is both a tribute to Inge Morath, one of the first women at Magnum, and to all the women photojournalists who often risk their lives working across the globe.

The project involved traveling in a towing unit, towed by a gallery on wheels, and photographing and presenting the work of the Austrian photographer and the eight women artists at the same time. The whole initiative is both a tribute to Inge Morath, one of the first women at Magnum, and to all the female photojournalists who often risk their lives working around the globe. It is also a gesture in support of all the women in the part of Europe explored by Morath, who often still live in male-dominated communities. To emphasize this aspect, four local artists were invited as part of the project: different workshops, meetings with artists or reviews of the portfolios of local female photographers took place in a car rented for the project. Morath's endeavor was placed in a broad social context and took on a real meaning within the cultural transformation that was and is represented by the experience of the Central and Eastern European inhabitants.

In the context of the Danube Revisited project, the words quoted as the motto of this article take on even greater significance. Eight photographers with a completely different way of perceiving the world, a different sensibility, a different artistic creed, but also different origin, age, experience, education and world view, eight photographers who follow in the footsteps of the events, but especially of the images from the Danube series, create works fundamentally different from Morath's photographs not only in terms of aesthetics, but also in terms of message, center of gravity in terms of meaning and artistic means. The works by Olivia Arthur, Lurdes R. Basolí, Kathryn Cook, Jessica Dimmock, Claudia Guadarrama, Claire Martin, Emily Schiffer and Amy Vitale show us a continuation of the changes that have taken place in the countries and cultures that make up Mitteleuropa. We see youth, freshness, couples kissing, the still waters of the Danube. We see the younger generation, already born in the era of the enlarged European Union, for whom national borders and divisions are much less restrictive, while access to education and information gives them the chance to make the best of the opportunities offered by the changing world. We see the architecture of provincial cities, the poetry of the mundane. We hardly recognize the places Morath photographs, though we certainly sense the atmosphere, the local color and cultural codes that have remained unchanged despite the passage of time and the development that has taken place since the Iron Curtain went up. What unites these two series is hope - visible in all the photographs. Hope that photography not only documents and describes the world, but can play a real role in changing it for the better.

The essay originally appeared in the 31/2018 issue of "Herito" magazine, published by the International Center for Culture in Kraków

Inge Morath © Inge Morath

© Inge Morath Foundation / Magnum Photos

© Inge Morath — The Inge Morath Foundation/Magnum

© Inge Morath — The Inge Morath Foundation/Magnum

Hall of Liberation at Kelheim, Germania de Vest, 1959 © Inge Morath Magnum Photos/ Forum

© Inge Morath Foundation / Magnum Photos

© Inge Morath—The Inge Morath Foundation/Magnum

© Inge Morath—The Inge Morath Foundation/Magnum

-topaz-denoise-enhance-sharpen--15883-m.jpg)