The too patient Danube

© Gyuri Ilinca

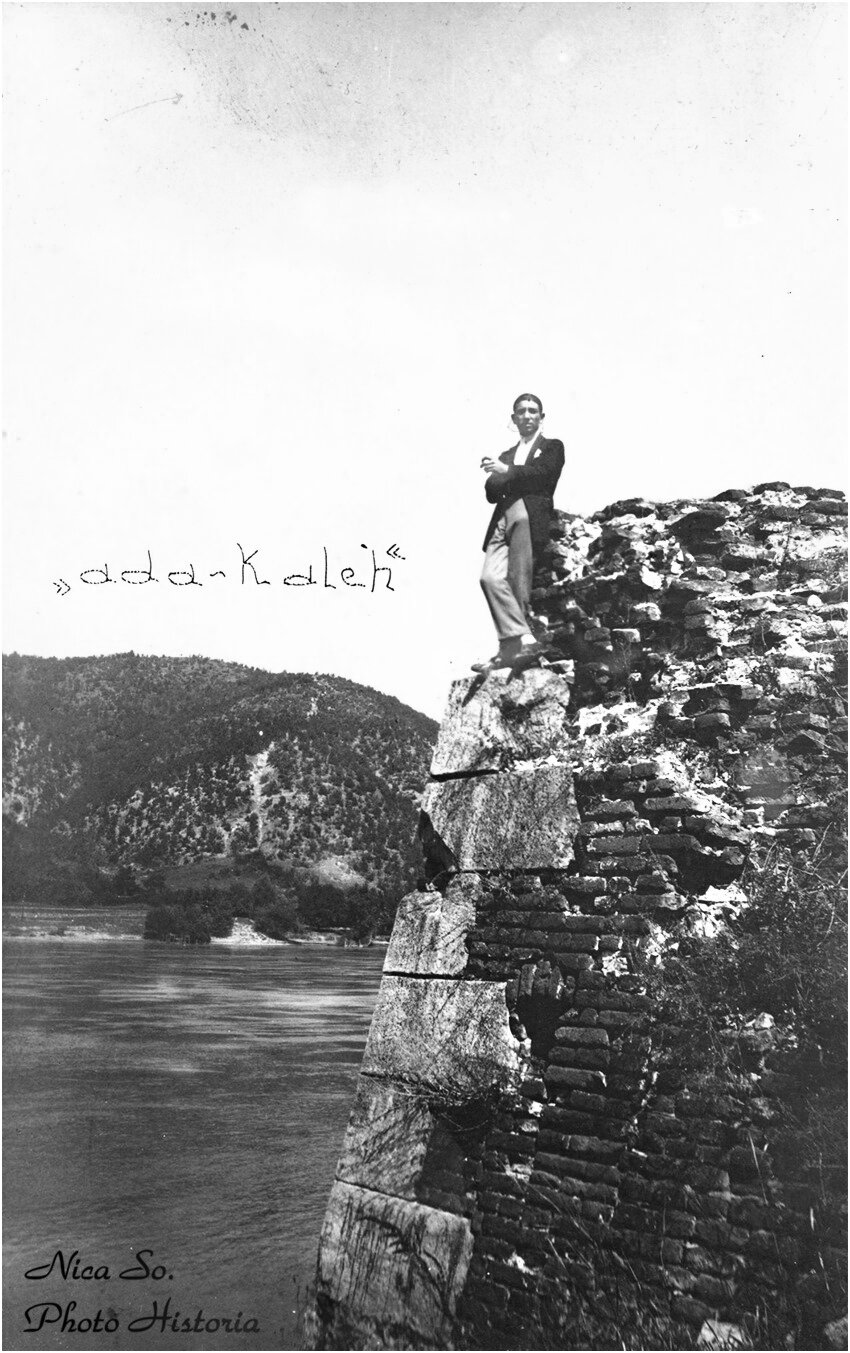

Anthem of Istria

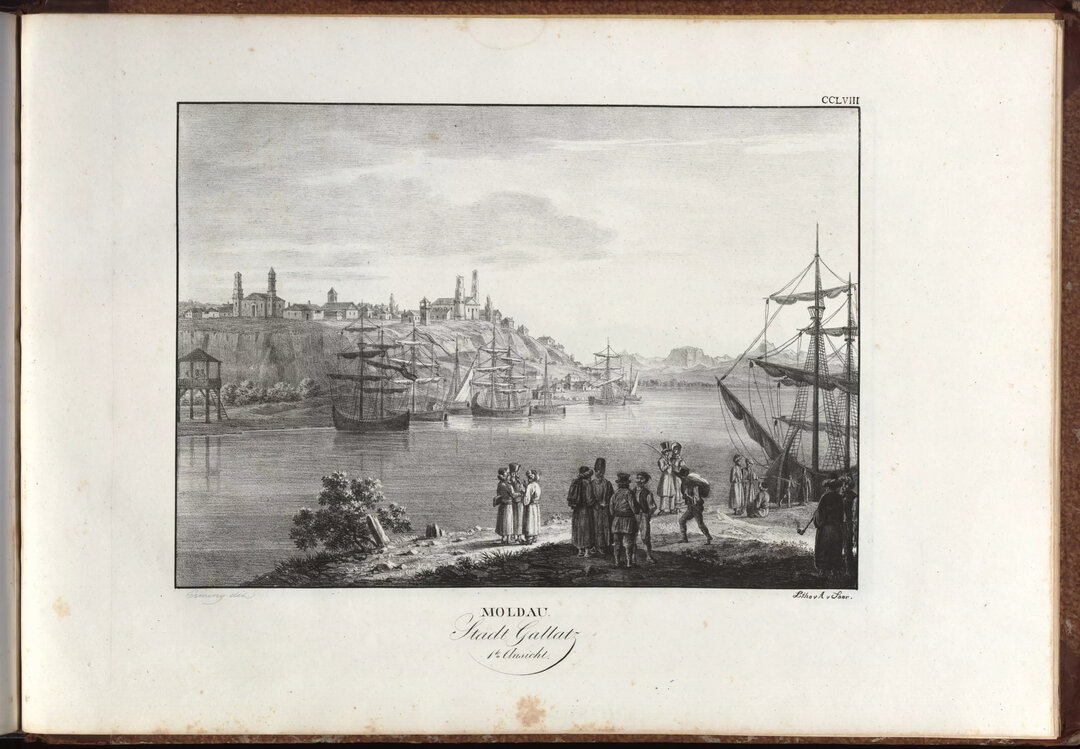

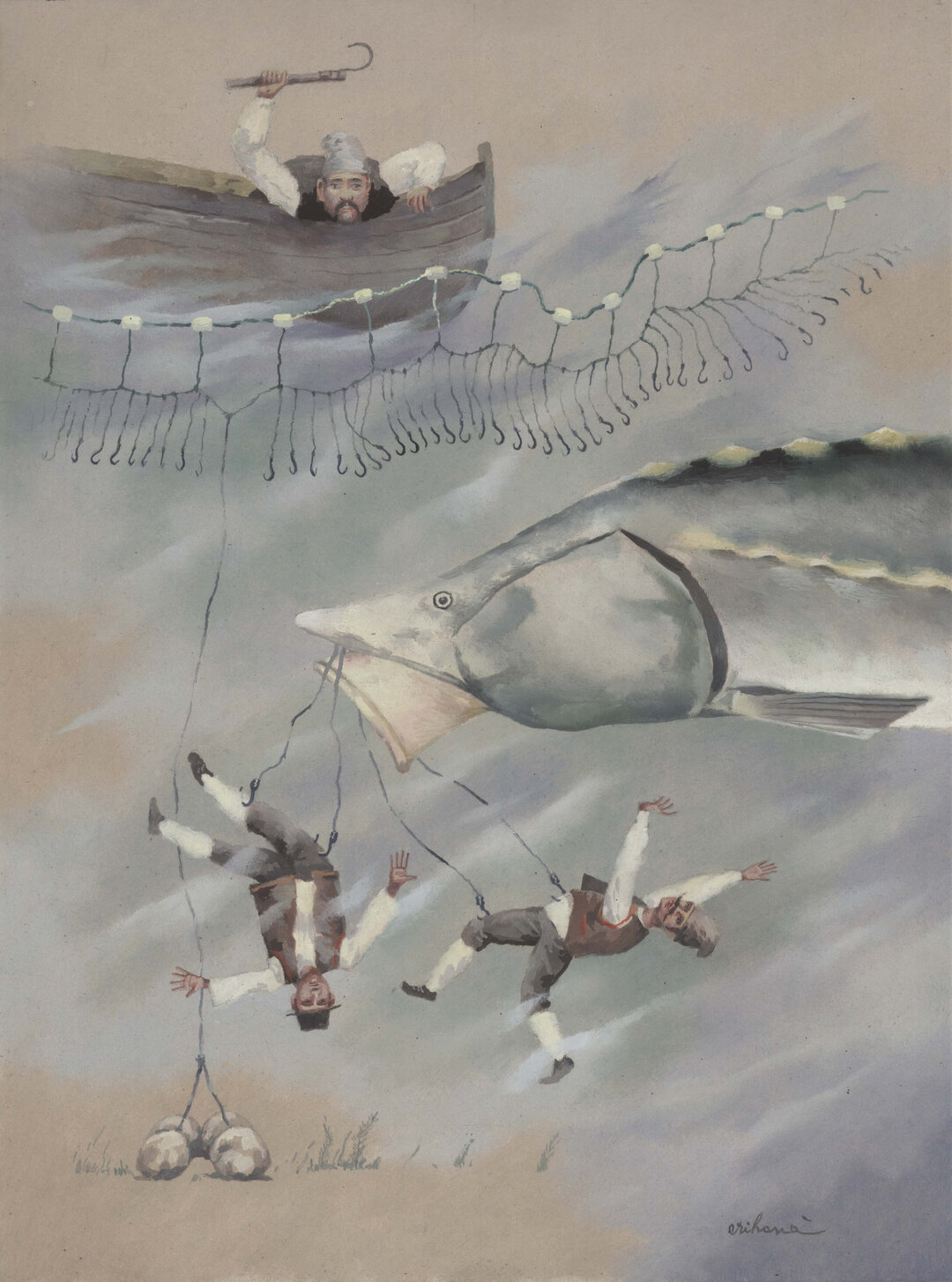

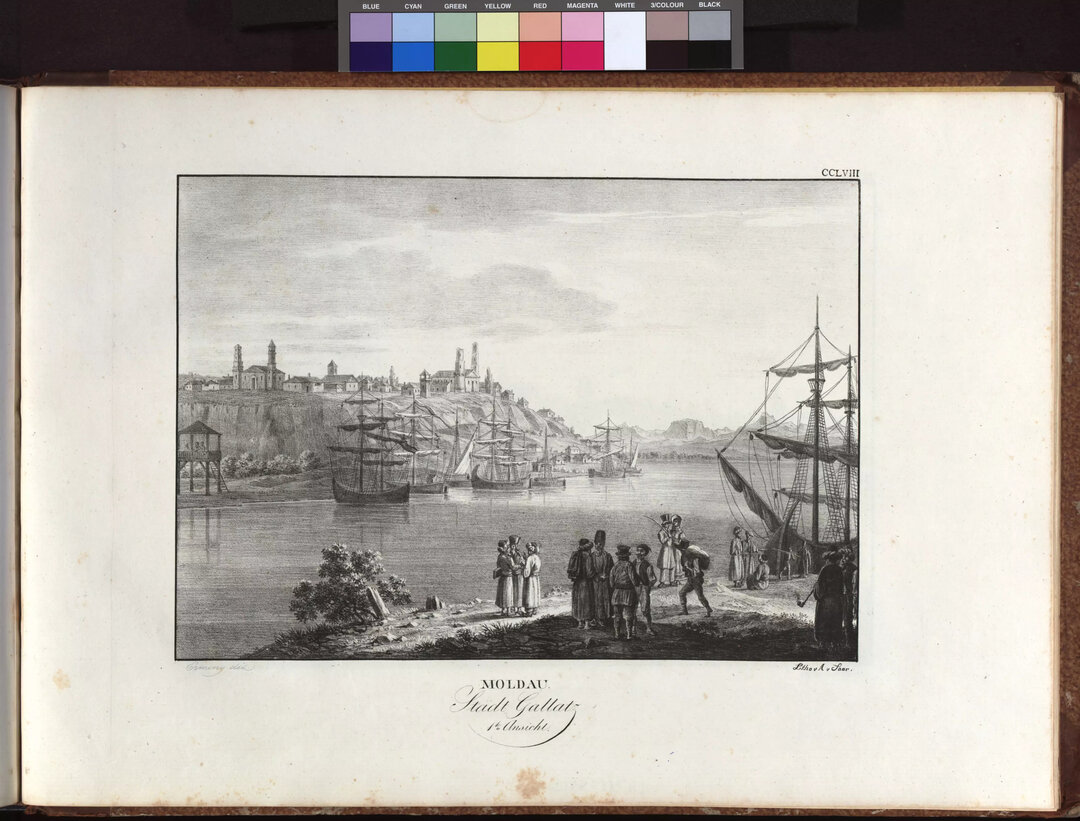

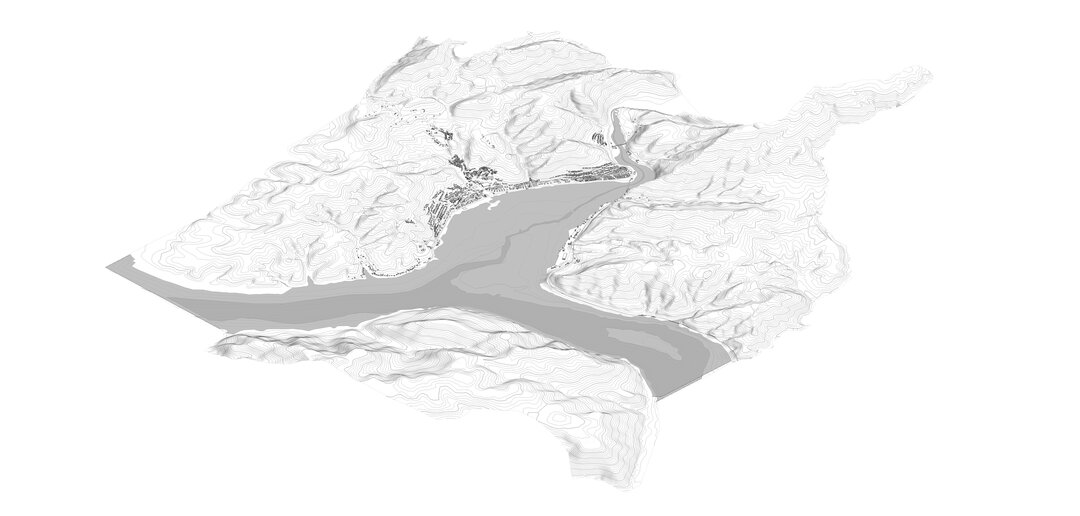

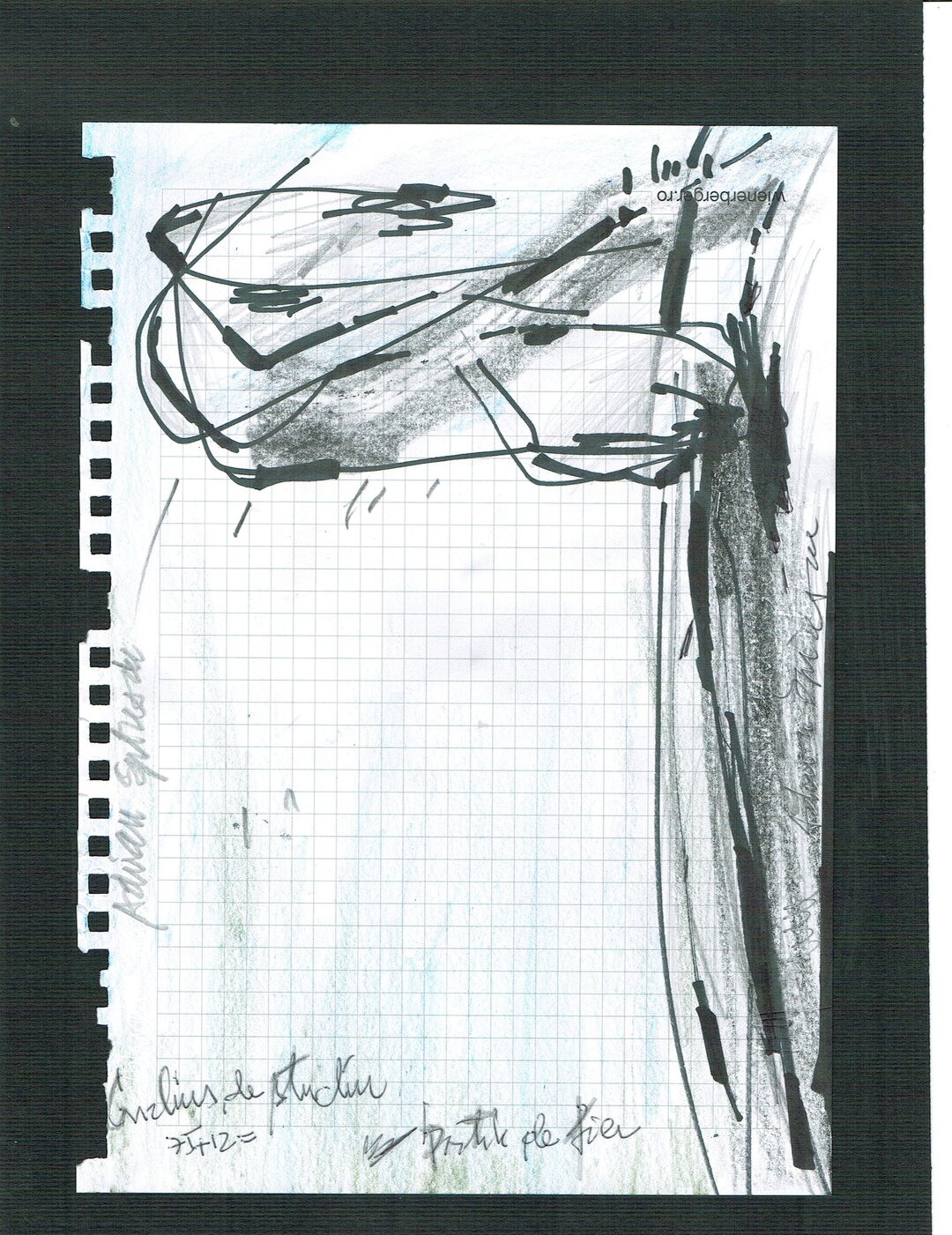

Mankind has always wanted to see the Danube as the "great integrator" of Europe. Associations, committees and personalities have worked on a long series of projects, all of which ultimately failed. But all this time, the Danube, ignoring politics and projects, has itself formed an existential and cultural world, under the influence of the various cultures that have been strung along its length. Though discontinuous, this construct has proved over the centuries far more durable and resilient than the empires that included it, used it, grew and then crumbled one by one. Although one of Europe's oldest trade routes, wars and political tensions temporarily thwarted the links between west and east - and there would still be work to be done today along its lower course. It left the poor Danube, often used as a border, but in its unbridled flow it has also proved that it can fluidize borders. And so, just as other territories twinned with the great waters are called Atlantic Europe or Mediterranean Europe, its entire area could one day be called Danube Europe. Donaueuropa. It will happen perhaps when one of the intended projects materializes. Geographically, the Danube would have no competition, no disruptive conflict, because it is the only great water that runs horizontally across Europe, and not in a south-north direction.

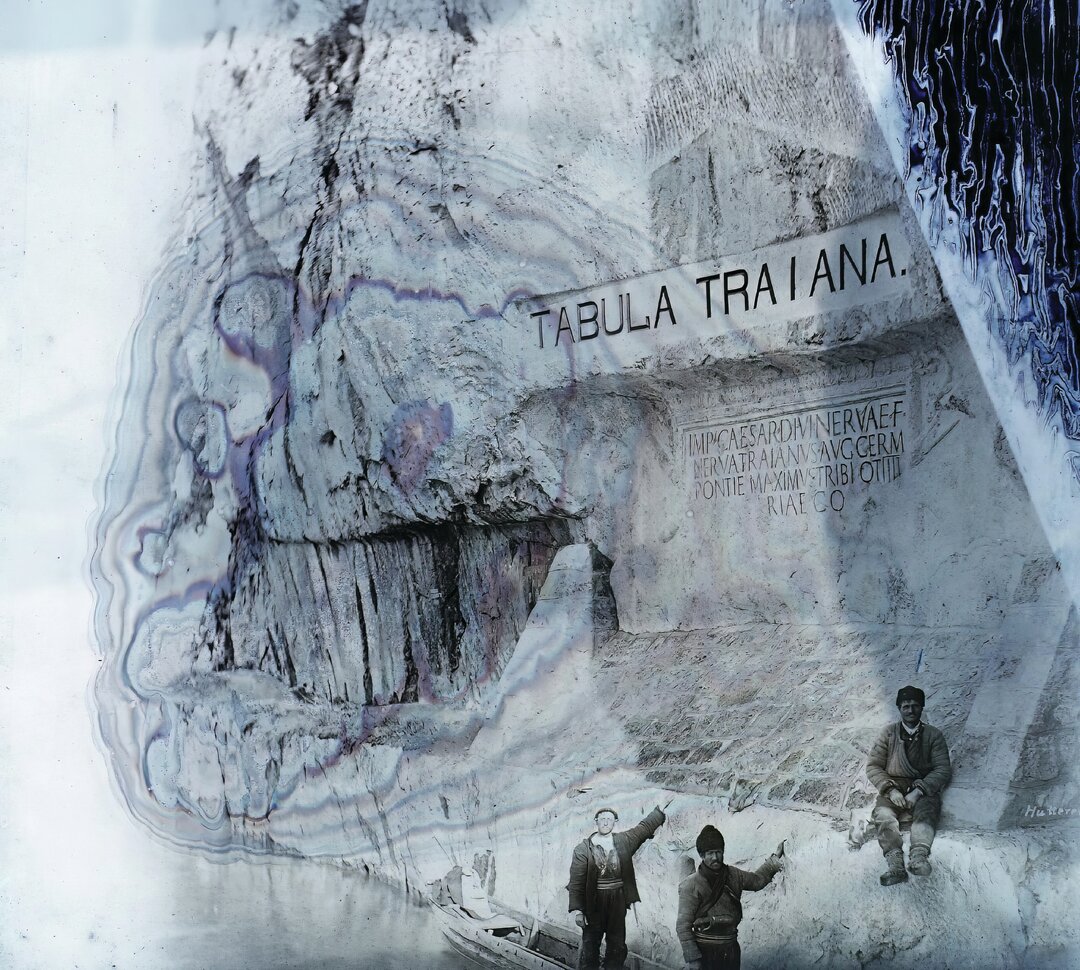

Hölderlin, the first figure on the podium of Romanticism, a poet par excellence and an important figure of German idealism, also saw the Danube as a unifier, capable of dissolving the world's disharmonies and bringing it closer to world harmony. In the last of three poems dedicated to the Danube, he calls it Ister(Istru)1. He calls it neither Donau nor Dānuvius, but uses the name established in glorious antiquity only for its lower course2. Isthus is credited with the ability to load the modern Western world with the values of the ancient East, which came via Greece.

To the poets and musicians, the bearers of culture from the 'Abendland of the Hesperides', the poet also points the way:

But it seems almost as if from the East.

He also tells us that the Greek hero Hercules also traveled the same path of waters from east to west, so that the Hyperboreans of the north could share the shady olive tree with the Arcadians of the south. The road of exchange - cultural, of course - is therefore not a one-way road, but has always traveled in both directions.

Hölderlin's reverse journey, that of Hölderlin, "the most German of the Germans", also shifts symbolic perspectives - cultural, of course. Symbolic, perhaps, is also the fact that the proposed trajectory happens to coincide with practical realities: even today, the surest way to measure the length of the Danube is from the spillway to its origins, that is, from a certainty to its uncertain sources. There are two sources. Or three. "Brigach and Breg make the Danube a whole", says a song about the two streams that flow out of the Black Forest Mountains and meet a little further downstream at Donaueschingen3. But before they meet, another small stream with its source there at Donaueschingen flows into the Brigach. Which, then, is the true source of the Danube remains a matter of dispute among the local patriots.

The poem begins festively: Come, come, fire! It is a greeting to the day that will bring new lights, new links that will bring the West out of the night of isolation. It continues nostalgically and optimistically at the same time, his plea for a small globalization in time and space, symbolically focused on the luminous Antiquity and the mysterious world of the North.

A sign is necessary,

Nothing else, that's wrong and right, so that the sun

And moon to bear in mind, inseparable...

After a hymn in a heroic-elegiac tone, the poem ends surprisingly with a doubt:

But what does that, the River,

No one knows.

Truly, Hölderlin was a visionary.

The ending remains open. We may find an answer in another of his poems4.

Come, to the Opening, my friend,

he says, and the invitation to openness is followed by an exhortation to search for the self. This river, then, which in reality flows eastward, in order to open itself to even further eastward, absorbs ancient culture and induces it, for dissemination, into the world of its own values.

This is exactly what Leo von Klenze achieved in Walhalla on the Danube. It may have been Ludwig the First of Bavaria or Hölderlin the First of Romanticism who prompted Leo von Klenze to materialize in marble the integrating dream of both. Walhalla, the palace of Odin in Norse mythology, the metaphorical paradise of heroes, is depicted in Leo von Klenze's project, which is similar to the Parthenon in Athens and dedicated to the heroes of German history. What a poetic mélange! A few years after the publication of his poem, Hölderlin could have witnessed the groundbreaking for Walhalla redivivus in 1816. And he would see the finished temple in 1842, a year before his death. It is just a short distance past Regensburg - coming from the East, of course - where the Danube bends at Donaustauf. And from up high, from the portico of the temple, from a hundred meters above the water's mirror, the wandering and exhausted Hölderlin could have admired the view of the all too patient river.

...Aber

allzugeduldig

Scheint der mir, 5

Friedrich Hölderlin was also a visionary because, in 1802 or 3 or 6, he foretold the new century in which cultures would come to know each other through direct contact, not through Hesiod and Pindar, but through the steam steam and railroad systems of transportation that were to develop. He also intuited that inter- and transculturality are organic, organic to the nature of both individuals and communities; that they are unstable, changeable, but also fluid like the Danube. He anticipated something, but he went even further than Michel Foucault, who, in 1967, saw the 19th century as the century of time and the 20th century as the century of space6. In a gesture proper to the 21st century, Hölderlin hybridized East with West, antiquity with contemporaneity and thus space with time, making up the cultural mix so dear to our present day.

Just as the mysteries(μυστήριον, mystérion), Greek cultic celebrations, developed around an enigmatic kernel, so the Istrian hymn is as festive as it is mysterious. Like all of Hölderlin's poetics, it has a linear course, but it is composed of a myriad of semantic knots cast over its interpreters. Heidegger also tried to unravel it, rejecting metaphysical interpretations of the poem in favor of more pedestrian meanings. I have developed, as can be seen, the meaning most favorable to our times, under the constellation of hybridity, inter- and transculturality.

And so visionary was the great Romantic that he poetically and subtly prefigured even the transgender trend: die Donau became der Ister. And der Ister was called to inseminate die Donau.

Dānuvius' youth as a traveler through Bavaria

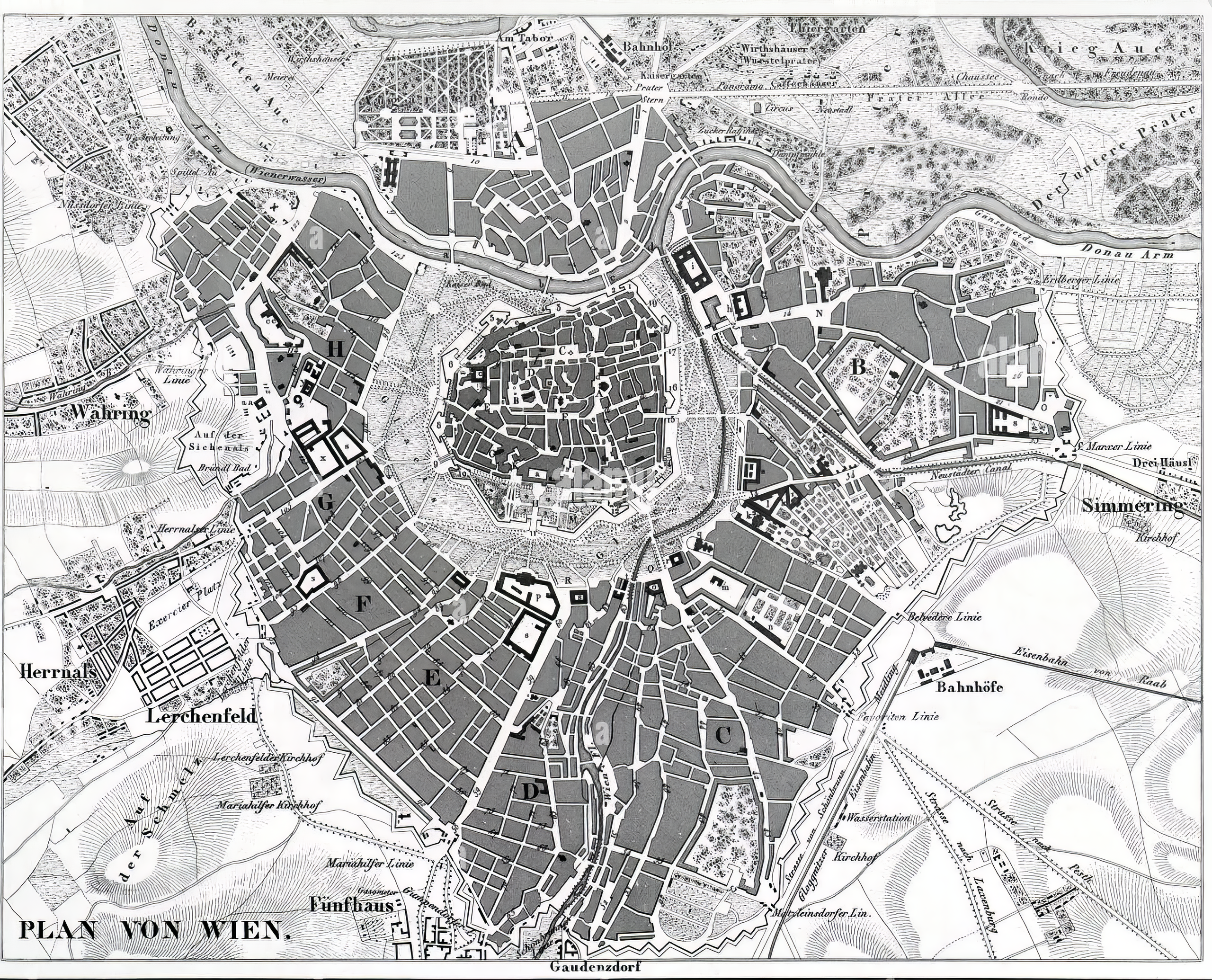

Dānuvius would, according to historical tradition, have been the upper course of the river - a young water, a river flowing softly, painterly but unpoetically disciplined from west to east, all the way to Vienna. (Further on it flows differently.)

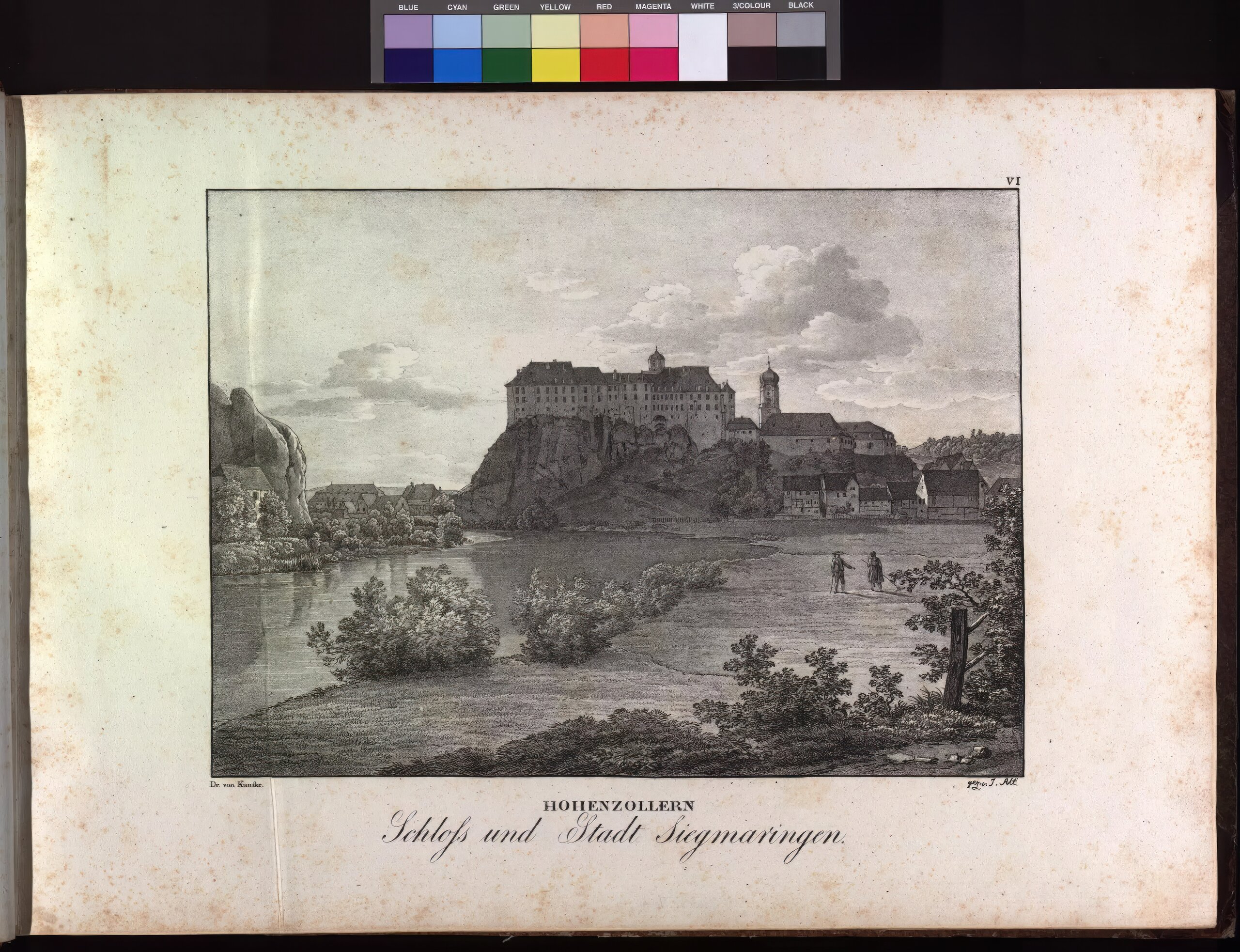

Dānuvius's childhood is dramatic. He was born into a ménage à trois, paternity disputed. In Donaueschingen, as a spring, there was only a puddle, but it had the good fortune to babble in the park of the princely castle. It wasn't until 1875 that Prince Egon III properly marked it. He built a pompous neo-Baroque enclosure, but above all he undertook serious underground hydrographic works. This turned the spring into a puddle with shingles. Who could have guessed its glorious future as an imperial river! As a brook, he quickly sheds his embroidered diapers, becomes independent and sets out on the road of life. As a baby, however, it has to swim with great difficulty across a plateau until it disappears underground (half of it actually goes underground and after many adventures flows through the Rhine into the North Sea), but it reappears in the fall. After slipping through a mini canyon, he finally wins the battle, definitively, at Sigmaringen. There he rests and rests, again under the protection of a high court. In fact, he has been admired from the cliff since the Paleolithic inhabitants of the settlement. (Before that, he used to loom unnoticed.)

Around 1050, the first castles rested their battle-steeled gaze. In 1540, the castle, in the meantime continually renovated and enlarged, finally received as its owner and resident the first nobleman of the von Hohenzollern family: Karl I. The castle later reverted to the von Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen branch, who lived there until 1850, when a Prince Karl moved to the town and gave the castle a humanitarian use. Since then, no member of the owner family has lived in the castle. Tourists are the ones who now watch it from above on the Danube of the Danube.

In 1881, a descendant of the high family became king of Romania: Carol I. Then Wilhelm I of Prussia commented: "We have a Hohenzollern at the source of the Danube and one at the mouth; not bad at all".

The Danube then invigorates itself through the Beuron strait, past the peaceful abbey, and gains the strength to push on.

Around Ulm, the river becomes a teenager, grows to navigable size and gets work from the hydropower stations. It now faces other hardships of life and slowly loses its candour: it is regularized and some of its natural landscapes disappear.

The first thing in Ulm that greets it from afar is the Münster dome tower, which everyone knows is the tallest in the world. But what they don't know is that it's only been there since 1890. And that the Sagrada Familia is waiting around the corner. But the tower has always been a height record anyway, and the whole dome was a multiple record. First, that it had a standing capacity of 22,000 people, more than double the city's population at the time. Then, because it was funded entirely by the citizens of the community. And finally, because it was built with the participation of most of the star European architects of the time - with site provisions, I think. Some of them are still scattered around the city today, of whom Richard Meier is the best known to us. And when the Danube wants to forget the present and stay in the Middle Ages, it creeps among the old Fachwerk houses in the fishermen's and tanner's quarter, showing them projections with the roofs down.

Up the Danube, onward and on to Ingolstadt. The Audi Forum is a bit far, but it makes a small loop to approach the Asam church (officially St. Maria de Victoria), which in 1732 was intended as the oratorium of the student congregation of Ingolstadt University. It shows that the students were esteemed and pampered. The baroque building was erected and designed by the brothers Cosmas Damian and Egid Quirin Asam, German Get Beget. Danube would love to mirror the rococo ceiling with a fabulous trompe-l'œil painting.

Other attempts soon follow. First an improbable detour to the Benedictine abbey of Weltenburg - said to have been in existence since the 600s - where he would be well advised to stop off at one of the oldest monastery breweries. After that he slips through another narrow gorge into another canyon, then relaxes. He solemnly passes the hill where Leo von Klenze has once again honored Germany's heroic history with his neoclassical-antiquizing architecture: the Befreiungshalle. The construction of the monument to the victorious battles against Napoleon began in the very year of the Walhallei's 1842 siege. This time, the rotunda takes the idea of the Roman Pantheon. When it was inaugurated, the choir sang a hymn written by King Ludwig I of Bavaria himself, which must have echoed down to the Danube.

It flows further on, under the pedestrian bridge over the Rhine-Main Canal, which it joins at Kelheim, to continue together, the three of them, on their journey that now links the North Sea to the Black Sea. And he reaches old Regensburg, the former Castra Regia of 179 AD. It's crossed many bridges, but like the medieval stone bridge of 1135, there's never been another. It's the oldest in Germany. It was financed by the merchants' guild, encouraged by Duke Heinrich the Proud. It was something of an eighth wonder then. Its builder, they say, brilliant as he was, would still have appealed to the devil not to risk failure. The devil's condition was that the souls of the first three to cross the bridge be delivered to him. And then the architect would send him a hen, a rooster and a poodle. In a rage, the devil would try to tear down the bridge, but he couldn't. Just as German troops didn't succeed during the war.

For 800 years it was the only bridge between Ulm and Vienna. It was crossed daily by merchants, especially salt merchants, but Conrad III himself marched across it in the Second Crusade, and Emperor Friedrich II Barbarossa marched from there in great force in the Third Crusade.

Through the town of Regensburg the bridge crosses both arms of the Danube, and a subway - a feat - leads directly to the city's main square, the cathedral. From there he, the gentle Danube, listens sometimes in the evenings to the boys' choir singing. They sing so beautifully that they even soften the stones of contemporary architecture at the new Faculty of Architecture or the Bavarian History Museum.

The most important event of the Danube in Passau is neither the Gothic nor the Baroque architecture, nor the Austrian border, nor the floods, nor the beautiful house called "Rock in the Waves" ("Fels in der Brandung", 2017), nor the modern St. Peter's Church, but its meeting with the rivers Inn and Ilz. In Passau, in the City of the Three Rivers, the great battle of colors is being fought. The winner is Inn, the green river. It's also the biggest and its water floats over the black Ilz and the supposedly blue Danube. From this union of forces, a large, mature river developed at Passau, and from now on it will be worthy of consideration as a river. Some wondered why the rest of the course was not called Inn. There you go. I'll still call it the Danube, like everyone else.

It's beautiful in Passau. The migrants like it too.

The Danube isn't blue anyway

It's never blue in Austria either. Research by a hydrological institute has shown that the Danube is: 59 days a year dirty green, 11 days brown, 46 days emerald green, another 46 days clay yellow, but most often it is steel green. Johann Strauβ may have called it blue just to make fun of it.

The Danube once flowed 1,300 km through the territory of the so-calledDonaumonarchy7. Now it crosses 350 kilometers of Austrian territory. Sic transit gloria mundi.

It crosses the border without a problem, because it is itself a kind of EU since the world was born. Halfway to Linz, the river suddenly feels like turning back. It changes its mind, doesn't turn back, and the result of this rock and roll movement is the spectacular Schlögen hairpin bend.

Green, gray or yellow ochre, the Danube enters Linz. It passes through the city in a daze. It seems only yesterday that St. Martin's Church was being built in the 8th century, and St. Florian's Abbey in 800, and later its Rococo library. How the world has changed, how brilliant the provincial town has become! Now it looks both ways and sees only eye-popping novelties in technology, architecture and the arts.

As he passes the emancipated city, he is reminded again, by the Danube, of the early Middle Ages: at Melk. Only that the abbey of yesteryear, which knew both Charles the Great and Otto the Great, and in whose fame Umberto Eco also shared, is now only the institution and the site on which the baroque building now stands.

It still winds on through the Wachau Valley, past vineyards, ruins, abbeys and memories of kings and emperors. In a castle here, Richard the Lionheart is said to have been a prisoner.

Finally, the Danube reaches Vienna. From 1919 to 1934, the city under the Social Democratic Workers' Party had become known as 'Red Vienna', and the Danube had almost begun to change color. Especially as it passed the Karl Marx Hof, it turned red.

Here in Vienna, in 1867, he heard Johann Strauβ swear after the rather apathetic-conventional reception by the public and the press at the first performance of the waltz An der schönen, blauen Donau. A waltz that had been dedicated to her, the Danau, with compliments. The composer, not too patient, shouted: "To hell with the waltz!" ("Den Walzer soll der Teufel holen!"). Success was not to come until Paris, when it was performed at the World Exhibition. And once again when, after the German troops left in 1945, the politicians in the Vienna parliament found themselves without a national anthem. And then the Blue Danube was sung.

NOTES

1 The poems "The Source of the Danube", "TheWandering" and "The Isthmus" are part of the cycle "Hymns of the Danube". "Istrul" was written sometime between 1802 and 1806 and is not known to have been completed. It does not bear a name given by the author, but the title was assigned to it by its first editor, justified and, as such, accepted.

2 Hesiod tells us that at the creation of the world, Tethys gave birth to Oceanus, among numerous other rivers, the so-called Ἰστρίη or Ἰστρος, read by us Istros. Such was the name of the Danube from the present day to the end of antiquity, but especially in its eastern course. The name Dānuvius or Danubius referred more to its upper course.

3 In fact, the song reads: "Brigach und Breg bringen die Donau zu Weg", correctly translated "Brigach and Breg set the Danube on its way" - but it does not rhyme.

4 Bread and wine (Brod und Wein).

5 'But far too patient/ It seems to me this one'.

6 Michel Foucault, Des espaces autres, 1967. The 19th century had been concerned with history, time, evolution, cycles. The 20th century was confronted with the obsession with space. The dominant idea was to build as much space as possible.

7 On March 10, 2023, it will be 520 years since the birth of Ferdinand I, the first monarch of the House of Habsburg, Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, at one time Prince of Transylvania, who ruled the empire from Vienna from 1526-1564.

-topaz-denoise-enhance-sharpen--15883-m.jpg)