Per dictam viam Braylam

On the known path of Braila

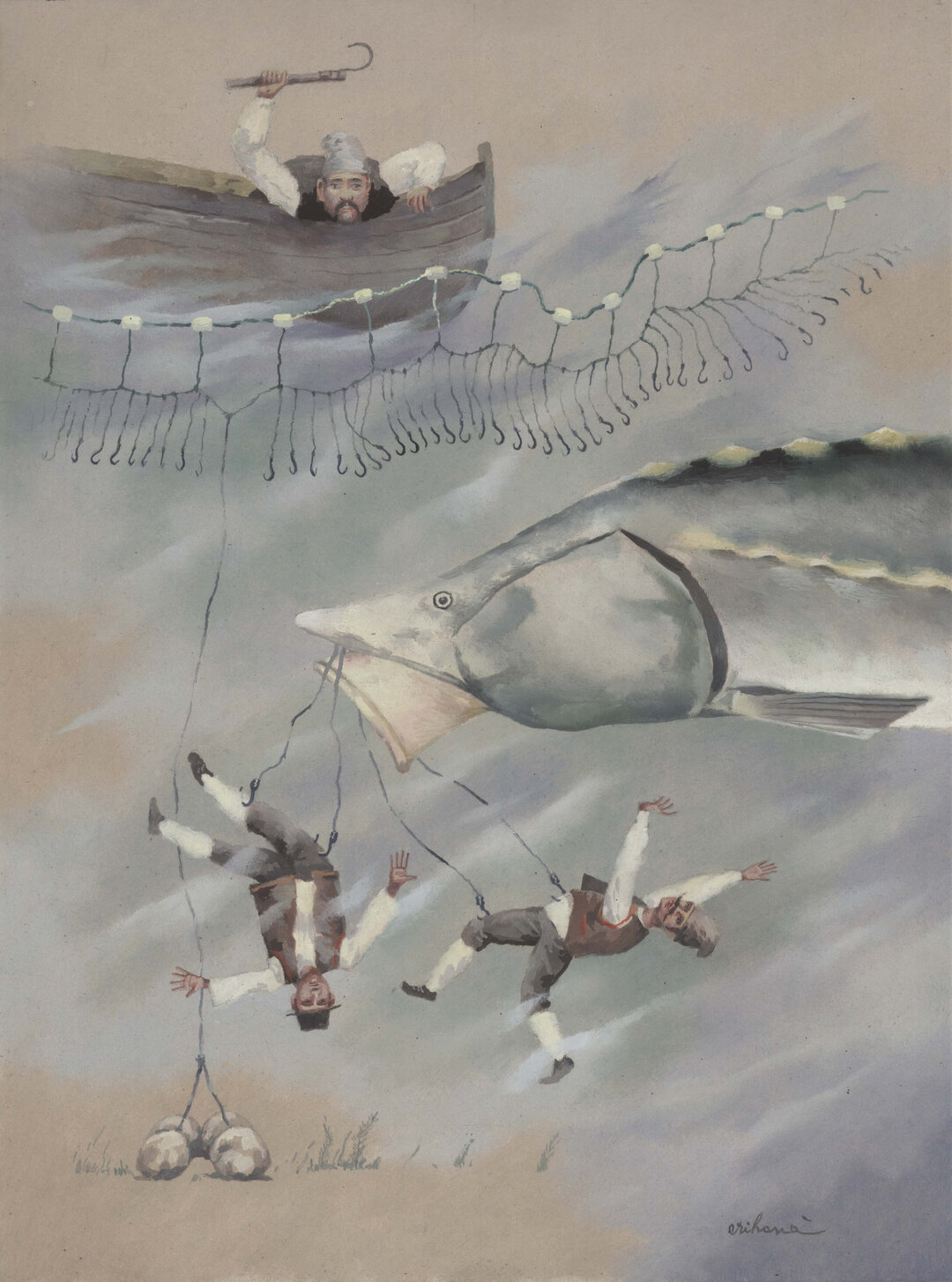

The rediscovery of Braila takes place at the beginning of the Middle Ages. The number of inhabitants of the region grew with their wealth. They actively traded fish caught in the neighboring pond, sold it to the Byzantines in exchange for gold perperions, and sent it by carriages to Wallachia and Moldavia and as far away as Poland. The old fishing village was transformed into a market town, an urban settlement. The port contributed greatly to this transformation, as ships arrived here, bringing foreign products and goods, which they sold to the locals, buying local produce.

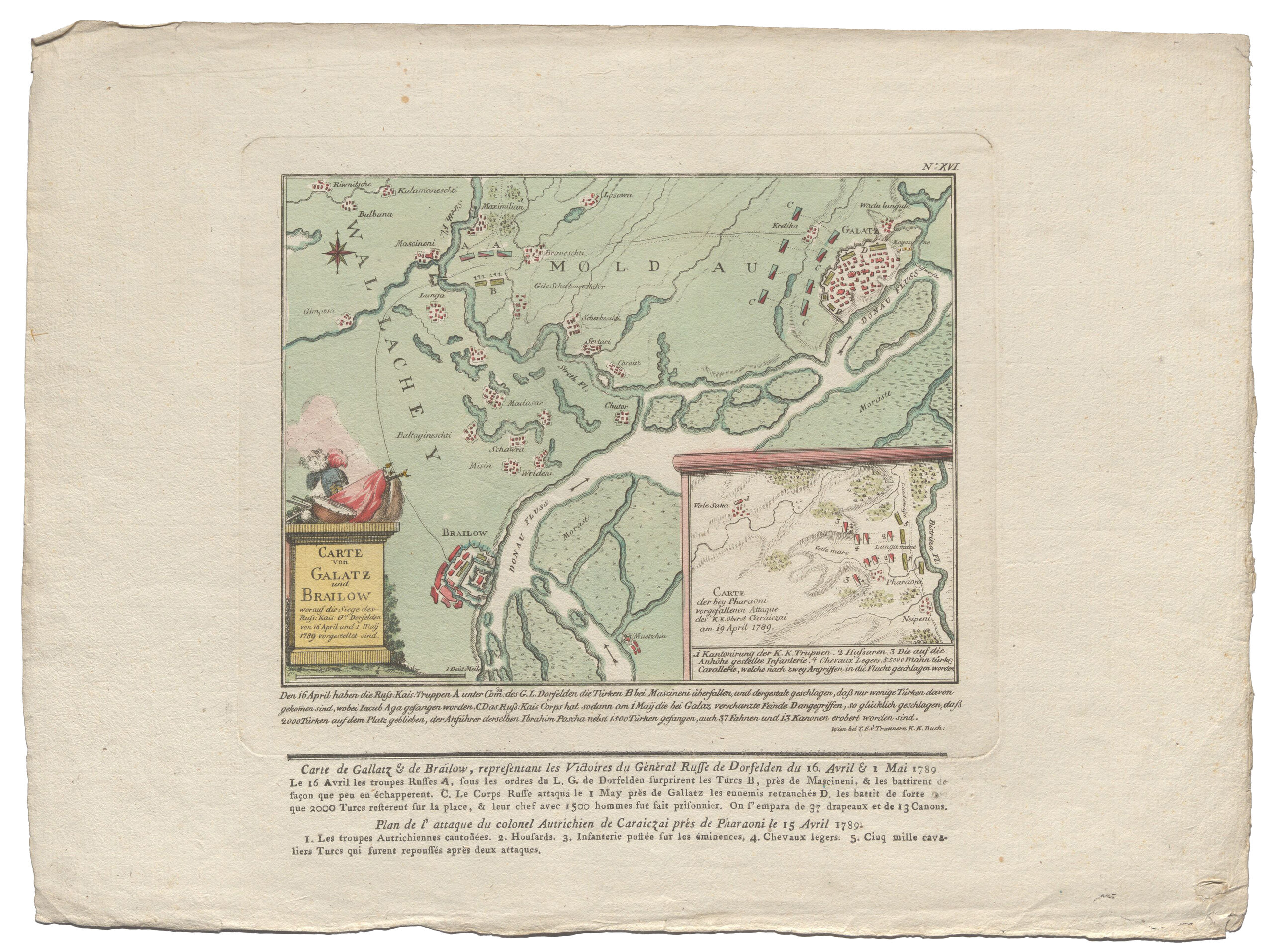

The actual name of Braila appears for the first time in an official document on January 20, 1368, in the commercial treaty that the voivode of Walla Wallachia, Vlaicu Vladislav (1364-1377), concluded with the merchants of Brasov, confirming 'the preservation of all the freedoms they have had in our land of the Mountains since ancient times', and deciding to exempt from customs duty goods that would take the road to Braila, 'per viam Braylam'.

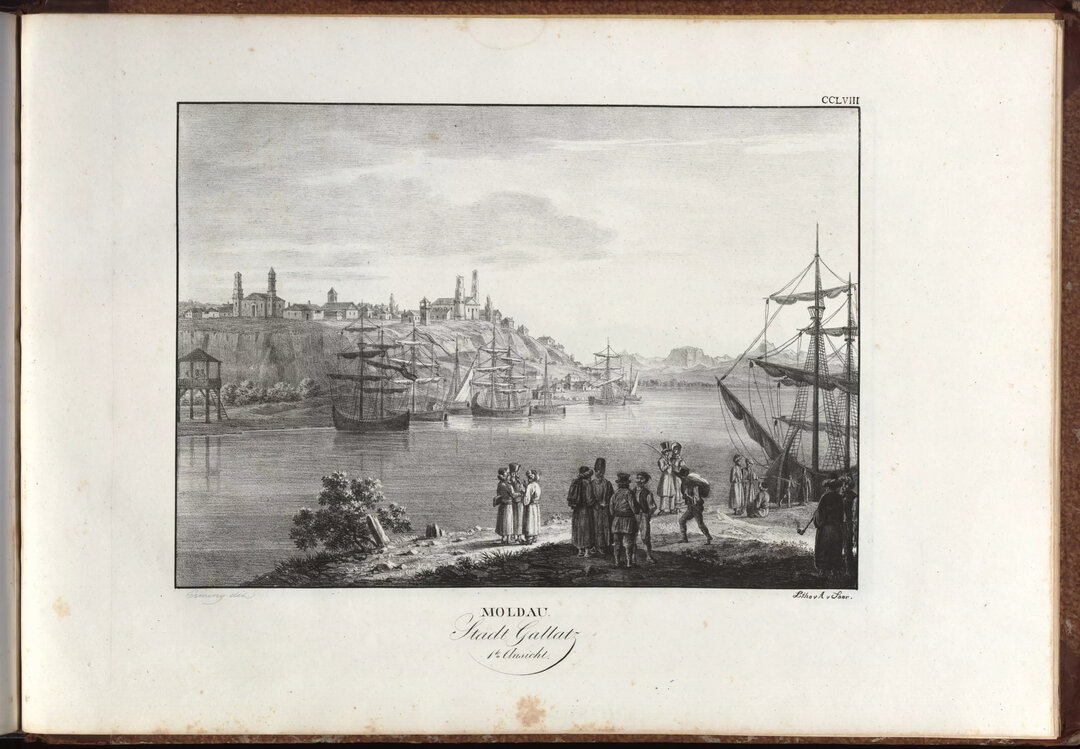

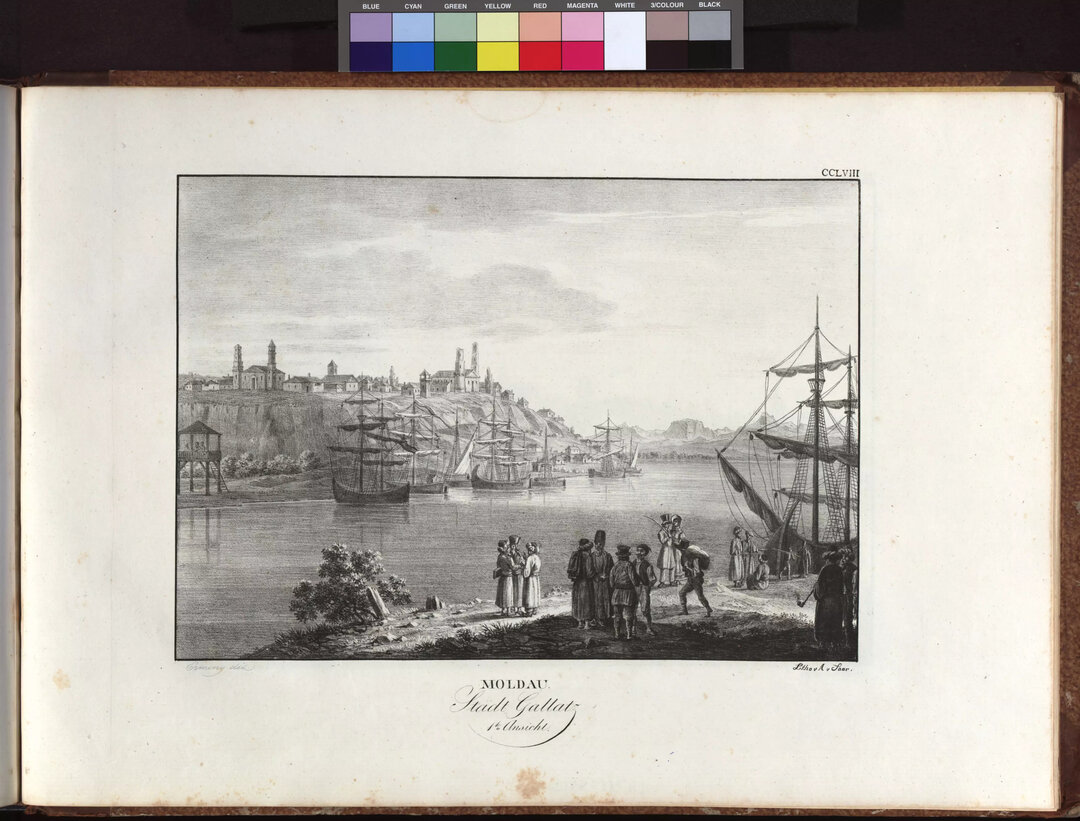

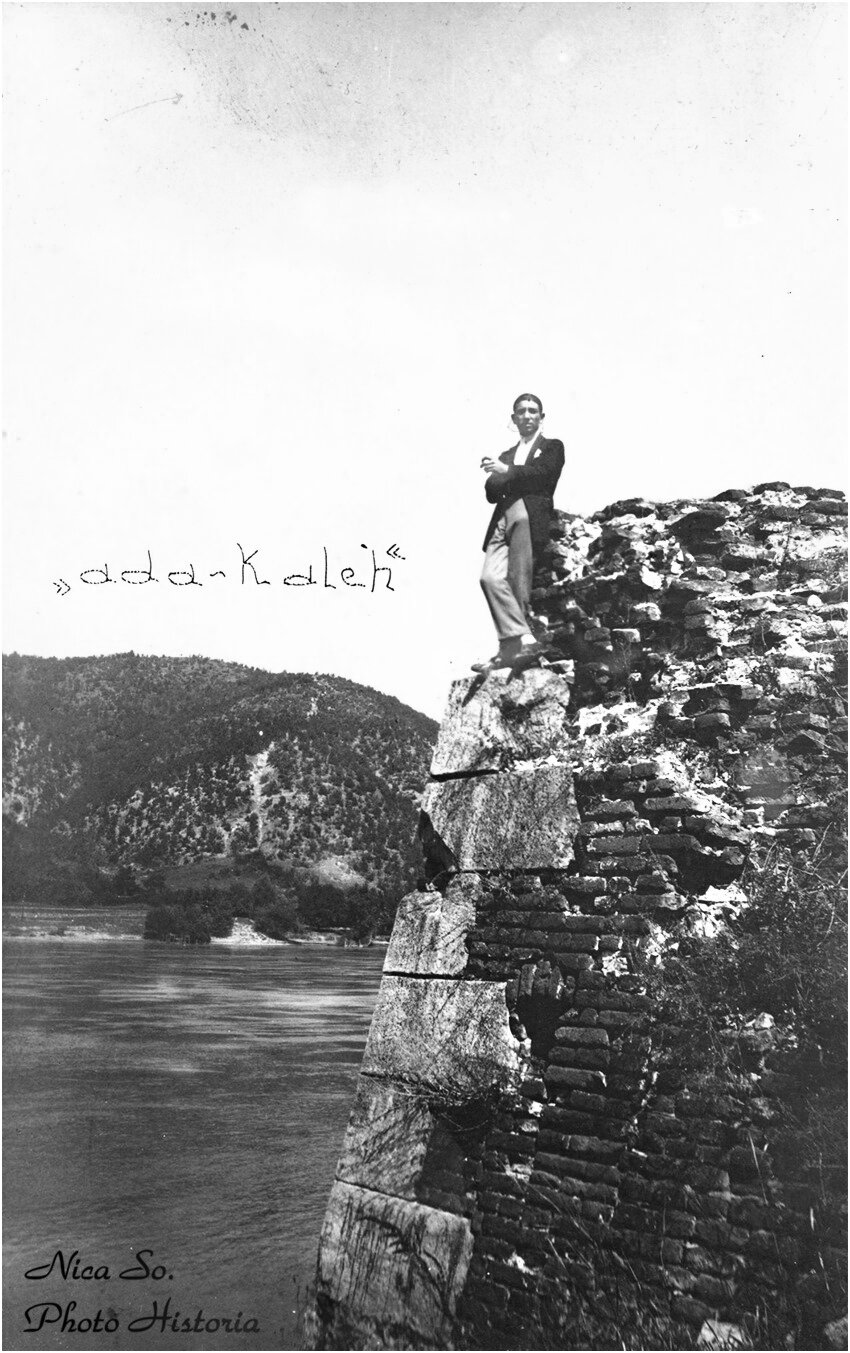

From the chronicles of foreign travelers in Walla Wallachia, we learn that the small settlement on the banks of the Danube was protected from possible attacks by a fortress strong enough, reduced to a castle with small towers, defended on one side by an arm of the Danube, where there is also a port, and on the other by an unconquerable redoubt. The tallest buildings were the fortress towers and three or four minarets, in a landscape dominated by bordered villages at the turn of the century. The Turks, during the Ottoman occupation, built a fortified fortress with a defensive wall overlooking the harbor and the river. The name Braila first appears in a document dating back to 1627.

Brăila is the only city on the banks of the Danube that dominates the river from the very high left bank, as Count De Langeron, a French general in the service of Russia, describes the city and the fortress from 1790-1812: 'Brăila is situated on the left bank of the Danube, a very high bank, so that the city dominates the river and its estuaries, which is unique in the whole course of the Danube. From Galati it has a very strong fortress, with two rows of walls and three ditches, impossible to take easily. The inner wall is made of stone with four strong bastions, then there is an earth rampart with five bastions, a glacis and a third ditch".

After a century of wars between the Russians, Turks and Austrians waged on the territory of the Romanian countries, Brăila was constantly hit, burned and rebuilt. In 1828, Brăila was the strongest fortress on the Lower Danube, despite the fact that it had no external fortifications. It was defended by some 8,000 Turkish soldiers recruited from among the inhabitants. It was a city of irregular, winding streets and houses were built of earth, wattle and daub and covered with foliage and reeds.

The European cultural model. In the 19th century, all over Europe, cities were being modernized, their technical and aesthetic problems solved. Modern Braila, a consequence of the liberalization of trade on the Danube, felt the need for legislation and an administrative structure to implement it.

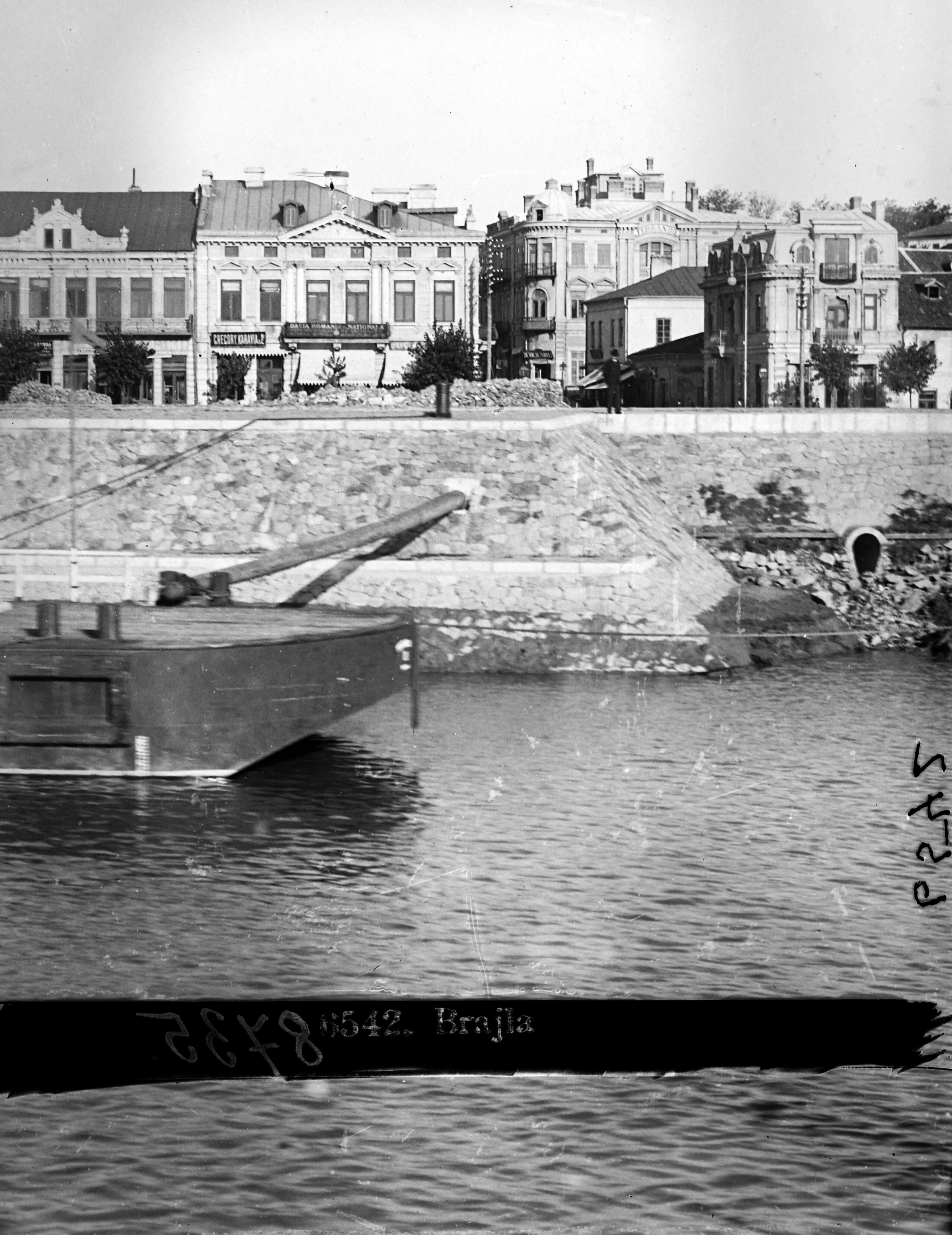

Brăila was rebuilt according to a modern urban plan, realized in several stages, which gives uniqueness to the city. The plan systematized the medieval settlement and made the most of the sloping, amphitheatrically oriented land facing the Danube. The city took on the appearance of a fan which the Danube opens out onto the plain. The urbanistic value of Braila is expressed by the continuity of settlement, it includes in its structure the three aspects of the evolution of the town: spontaneous, organic development (up to 1829), modernizing intervention, through the 1834 city systematization plan and the expansion in stages, based on a pre-established plan, which took into account the already existing structure; it preserves, with few modifications and of recent date, the entire dowry of the built-up area in the second half of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century.

The first stage of its development shows images of a medieval settlement, superimposed on images of a fishing village, with images of the market, the Turkish fortress and the port city.

A new life began in the city on the Danube, the freedom of trade on the old river - the declaration in 1836 of the status of a free port, when the Chamber of Commercial Arbitration was established, in 1882 the Grain and Commodities Exchange, where the price of grain in Europe was decided, then the Commercial Court and the Commercial Bank - would bring the prosperity that would raise the city. From 3,000 inhabitants in 1828, the population reached 14,000 in March 1843. In order to encourage the population of the town, it was decided that the site of the former fortress and the vacant land should be subdivided and sold only to those who had the means to build. The trade attracted a large number of peasants from neighboring counties and districts, Transylvanian merchants and moccasins, inhabitants of the Balkan territories and Dobrogea, which had remained under Ottoman rule, and Russian and Lviv inhabitants. From 1836, any foreigner who sent a written pledge of allegiance to the town magistrate could buy houses or warehouses in the town.

Although the town's urban economy was dominated by the export of grain, other occupations developed over time. Of these, tavern keepers and fishermen were important in the first half of the 19th century. Over time, the occupational structure of the settlement diversified along with the ethnic structure, so that in 1837, the magistrate recorded German and German tailors, German and German carpenters, clockmakers, silversmiths and Jewish tinsmiths, etc. Over time, a climate of tolerance was created, which was amply expressed in the multitude of places of worship erected, representing all the rites present in the town: Orthodox, Catholic, Evangelical, Mosaic, Lutheran, Calvinist, Muslim. Nowhere else in Romania have Romanians, Turks, Greeks, Armenians, Jews, and Lipovans got on better than here on the banks of the Danube, the river being a link between ethnic groups.

In Brăila, the streets were lined, lanterns were erected, the central square was paved, the road to the port was laid out, a military hospital was set up, pharmacies, a weather station, parks and gardens were laid out, printing works, a bank, a barracks and a theater were established, Rally (today's Maria Filotti), a girls' school, a gymnasium, the location of future institutions, urban spaces, the harbor area, where the quay will appear, delimiting the area for the porto-franco, docks, railroads and several factories are built. Trade and transportation will dominate the economy until the First World War. Braila was the hub for the transportation of cereals and other goods by rail and river. The major trade routes were to Istanbul, Odessa, Thessaloniki, Athens, Jaffa or Port Said.

Town planning. On the orders of General Pavel Kiseleff (1788-1872), the city council and a committee for the beautification of the city were set up. In 1830 a plan of the city was drawn up, called the Riniev plan, which presented the city's perimeter in a definitive form. According to this plan, the city had the appearance of a rural settlement with scattered houses, surrounded by lanes leading to the more important roads of Silistria, Bucharest and Iasi.

The second town plan was drawn up by order of General Pavel Kiseleff in 1834 by Rudolf Artur Baron von Borroczyn, a Russian officer of German origin, who, after participating in the Russo-Turkish War of 1828-1829, settled in Wallachia, working as a topographical engineer. He proposed certain urban improvements to the 1830 plan of Colonel G. Riniev, designed to modernize the settlement on the Danube bank. Thus, the modernizing intervention took into account the configuration of the town, integrating it into the new composition. The proposed plan connects the city to the harbor, extending the road from Bucharest to the east, making it an important urban axis. Urban spaces have been highlighted, the city center becomes a public space. The new outline of the city is superimposed on the boundary of the old Ottoman fortress. The entrance and exit of the city are preserved. The plan offers the possibility of future expansion according to a unified concept, without radical changes in the perimeter and spatial structure of the town.

The account of the Church of Scotland's 1839 mission of research among the Jews, written by missionaries Andrew A. Bonar and R. Mc. Cheyne, gives a true picture of Brăilei: "The town clean, well ventilated, with wide streets, some even paved. Many brick houses, but most of them one-cated. Well-grown groves of acacia and olive trees. The crosses of churches gleaming in the sunlight impress with starry globes atop their arms. Domesticated storks in the courtyards. The Danube, deep and swollen, runs past the town. The grain trade is growing steadily, and the fair is increasing in importance. The population, 6,000 souls, is prosperous. The usual mode of travel is by cart, a rudimentary wooden vehicle with small wheels.

In 1856, the architect Kuchnowsky drew up a plan of the town, listing the names of each street and the three barriers: Silistrei, Bucuresci (formerly Kiseleff) and Galati (formerly Iasi).

The next plan, drawn up in 1870, proposed an expansion of the city in successive stages. It envisaged the repetition of the subdivision in circular arcs up to the new boundary, formed by a road, the Side Street, doubled by a ditch. The symmetrical composition and the rigorous radial-concentric layout of the streets, open towards the Danube, were essential to ensure the convenience of intra-village circulation and easy communication with the outside. The systematization plan took into account the existing situation, integrating the old area into the composition.

The development of the city was continued through the radial concentric layout of the streets, open towards the Danube, the most important being the Alexandru Ioan Cuza, Independenței and Râmnicu Sărat boulevards. The city developed on an axis, the commercial street, the current M. Eminescu, formerly Calea Regală, which gives us the image of its historical and economic evolution. This axis was extended towards the harbor area.

During the 18th and 19th centuries, Braila expanded and developed according to urban plans drawn up by the city's architects. The following engineers-architects, all foreigners, should be mentioned as key figures in the urban development of Braila in the first half of the 19th century: Riniev, Borroczyn, Blaremberg, Thillaye, Arcudinschi, Andrei Covaci and Hartel. As can be seen, they were all foreigners. The first Romanian architect was appointed by the Domnesc Decree no. 258 of July 7, 1859, following a competition. His name was Dimitrie Poenaru. He was followed by Carol Rogusky, Constantin Budeanu and J. Dufuor.

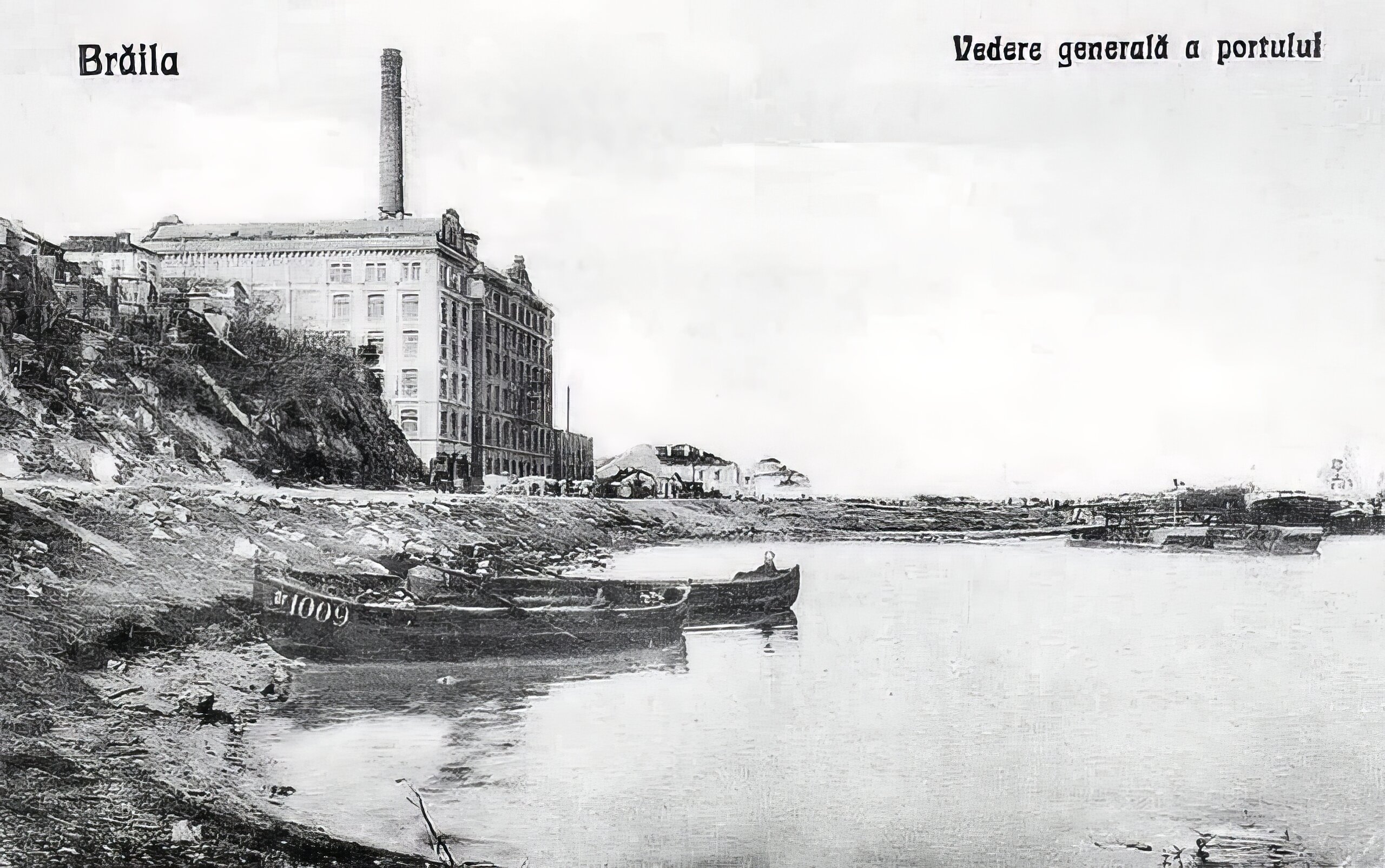

For hundreds of years, the economic activity of the city of Braila was confused with the port activity, which was mainly commercial. Thus, links were formed with countries outside the Ottoman Empire long before 1829. The port retained its importance during the Ottoman administration.

The modernization of the port went hand in hand with urban modernization after 1829. The first development project was drawn up by the Department of the Interior and signed by the Ofisul of Prince Alexandru Ghica in October 18403. The ruler had in mind the strengthening of trade links with Great Britain, which is why he declared Brăila a free port on January 13, 1836, and Galati in 1837.

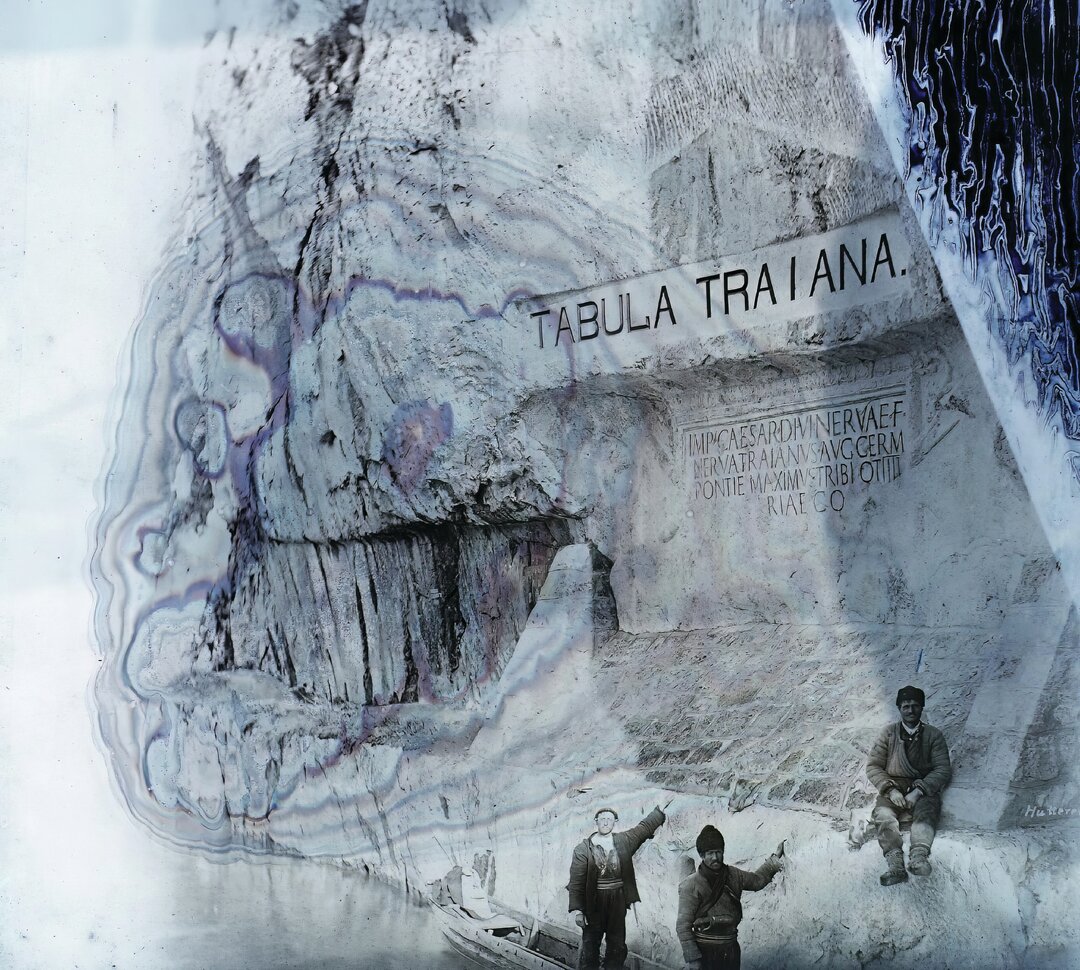

Of particular importance for navigation in these ports was the appearance of Austrian agency ships, which linked Central Europe with the Levant. In 1834, the 'Argos' arrived in Braila, and a regular service was set up between Galati and Vienna, carrying goods and passengers. In 1837, the first ship from Constantinople arrived in Brăila, also Austrian. This port was the terminus point for seagoing ships, which were unable to go further up the Danube because of the river's shallowness.

We can say that the main factors of the city's modernization were foreign merchants and industrialists who brought important financial resources and their pragmatic mentality. A number of institutions were founded that favored trade relations (Chamber of Commerce and Industry in 1864; the Philemboric Bank or bank for trade in 1845). Along with these, a series of hotels had to be built, located on the main thoroughfares, near the markets, on the commercial fords, many of which have survived to this day.

Since 1841, numerous requests for land in the port area for the construction of warehouses for the storage of goods led to the subdivision of the area and the emergence of a straight street grid parallel to the river.

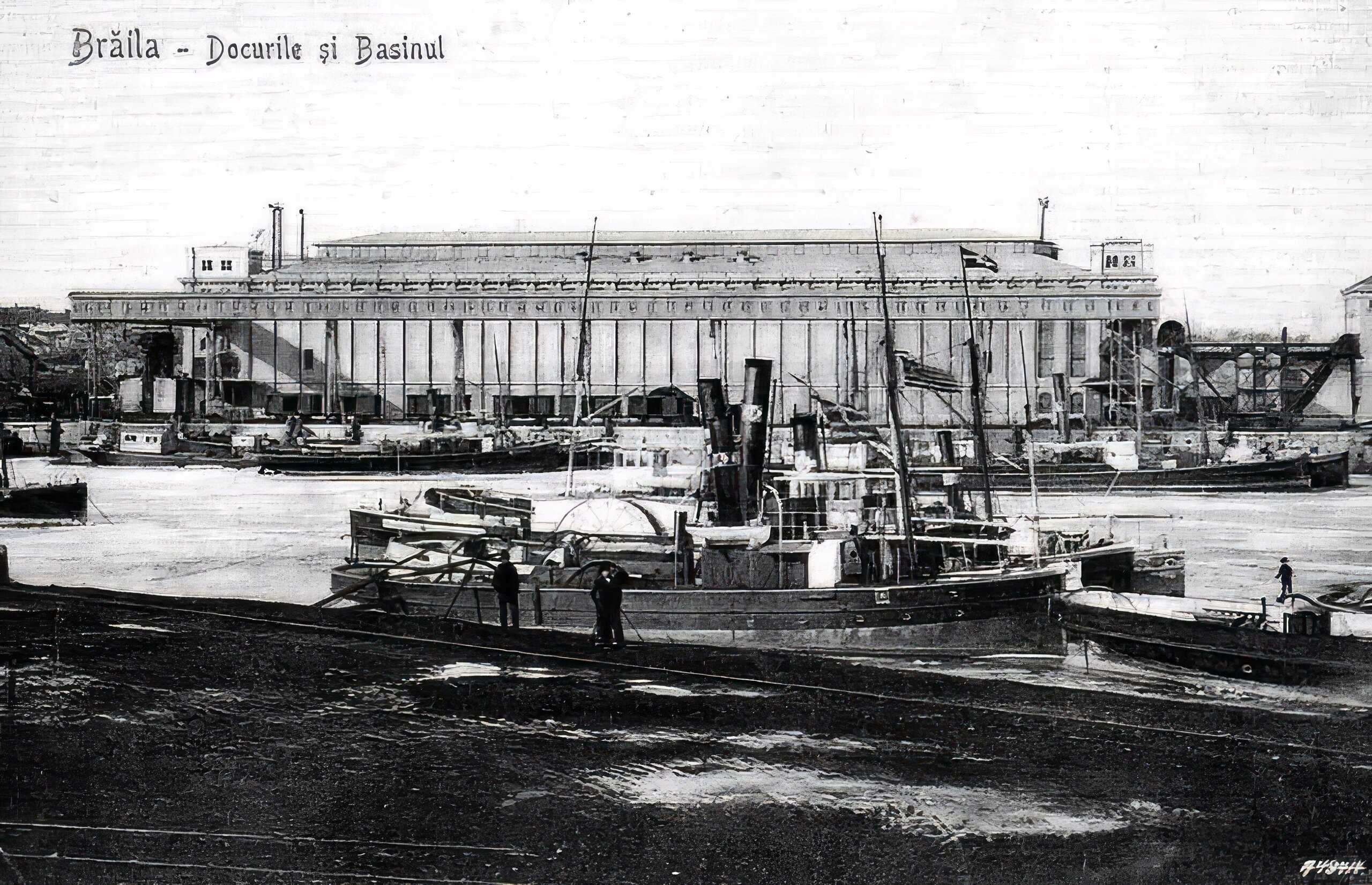

The most extensive modernization projects of the port of Braila were initiated between 1886 and 1891. These transformations were necessitated by the increase in port traffic with large tonnage ships, after the Sulina canal had been cleaned and the sea mouth deepened. The works of warehouses, wharves and grain warehouses with silos in the ports of Brăila and Galați were carried out by the General Directorate of Railways, headed by Anghel Saligny5, between 1884 and 1886. In 1883 the construction of the docks of the port of Brăila started. The construction engineer Anghel Saligny used reinforced concrete for the first time in Romania in 1888, for the construction of quays and berths in the port of Brăila (1883-1892), building reinforced concrete silos in the ports of Brăila (1888) and Galați (1889) based on his own inventions. Designed and built under the direct guidance of Anghel Saligny, the silos could hold over 25,000 tons of grain (30 m x 120 m at the base and over 18 m high). The hexagonal cell walls of the silos were also made, also a world first, from pieces fabricated on the ground in the form of slabs. Prefabrication of the slabs on the ground, stiffening and junction corners, welding of the metal bars and mechanization during assembly were other world firsts. The companies that made the silos were Romanian and foreign - Dutch, German, French. The whole project was large-scale, the grain store was 120 m long and 30 m wide. The 336 silos had capacities of 50-100 tons each. The entire construction was equipped with modern machinery.

Also in Brăila, Anghel Saligni built between 1904-1906 the Old Captain's Office, today's River Railway Station, symbol of the Port of Brăila and a heritage building.

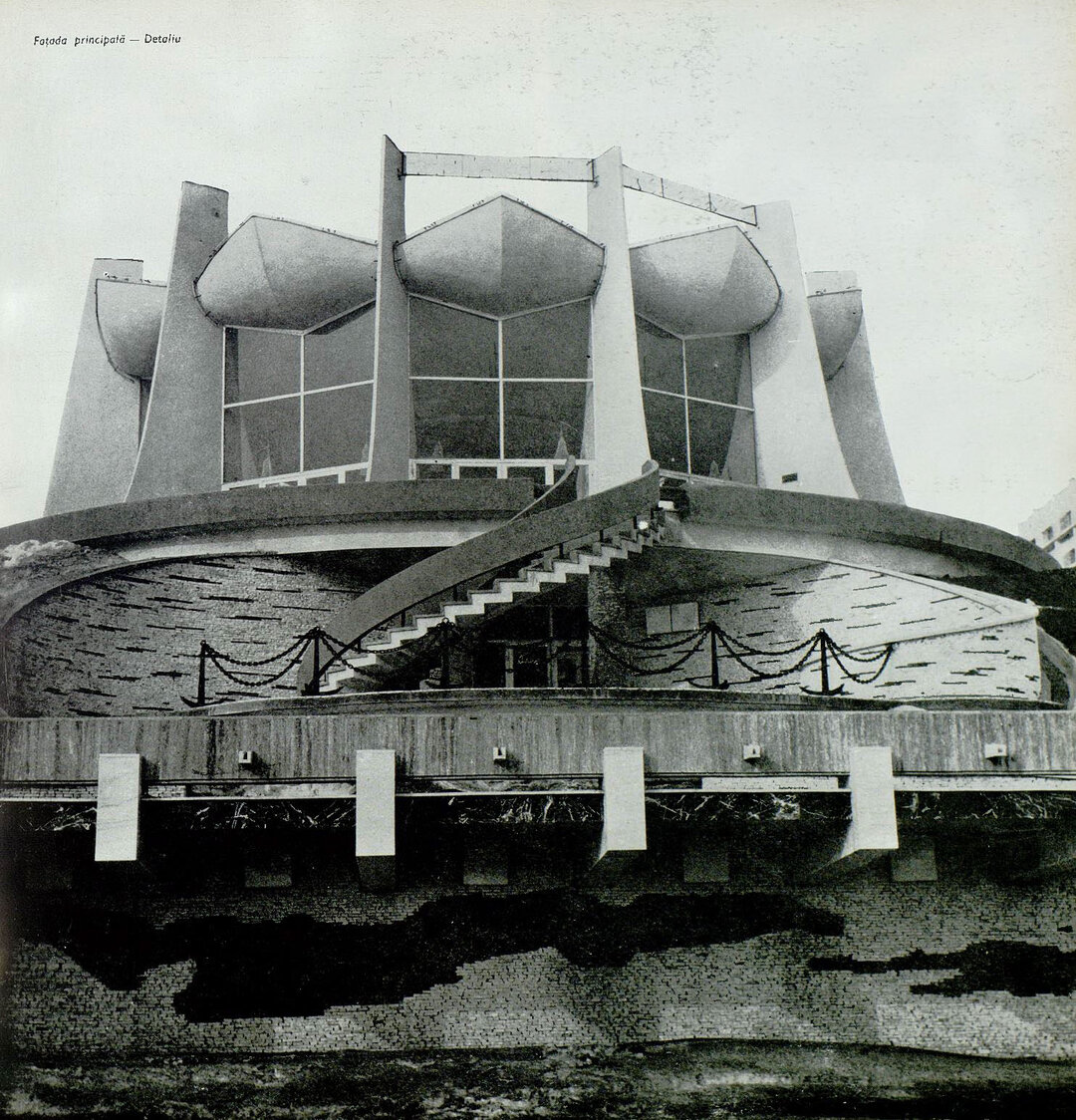

Brăila after the Second World War. After the end of the war, Brăila, along with the entire Romanian economy, entered a process of forced industrialization. Alongside the nationalization of industry, new factories built by the communist regime also appeared. From an urban planning point of view, whole areas were demolished in Brăila, as the communist power needed a new headquarters and other institutions were built. New neighborhoods of blocks of flats were also built.

The old center of Brăila, with a bohemian air, a mixture of coquetry, modernity and traditionalism, narrow cobbled streets and buildings full of stories, became after 1989 an architectural and urban planning reserve, included in the national list of historical monuments and is waiting for a return to life.

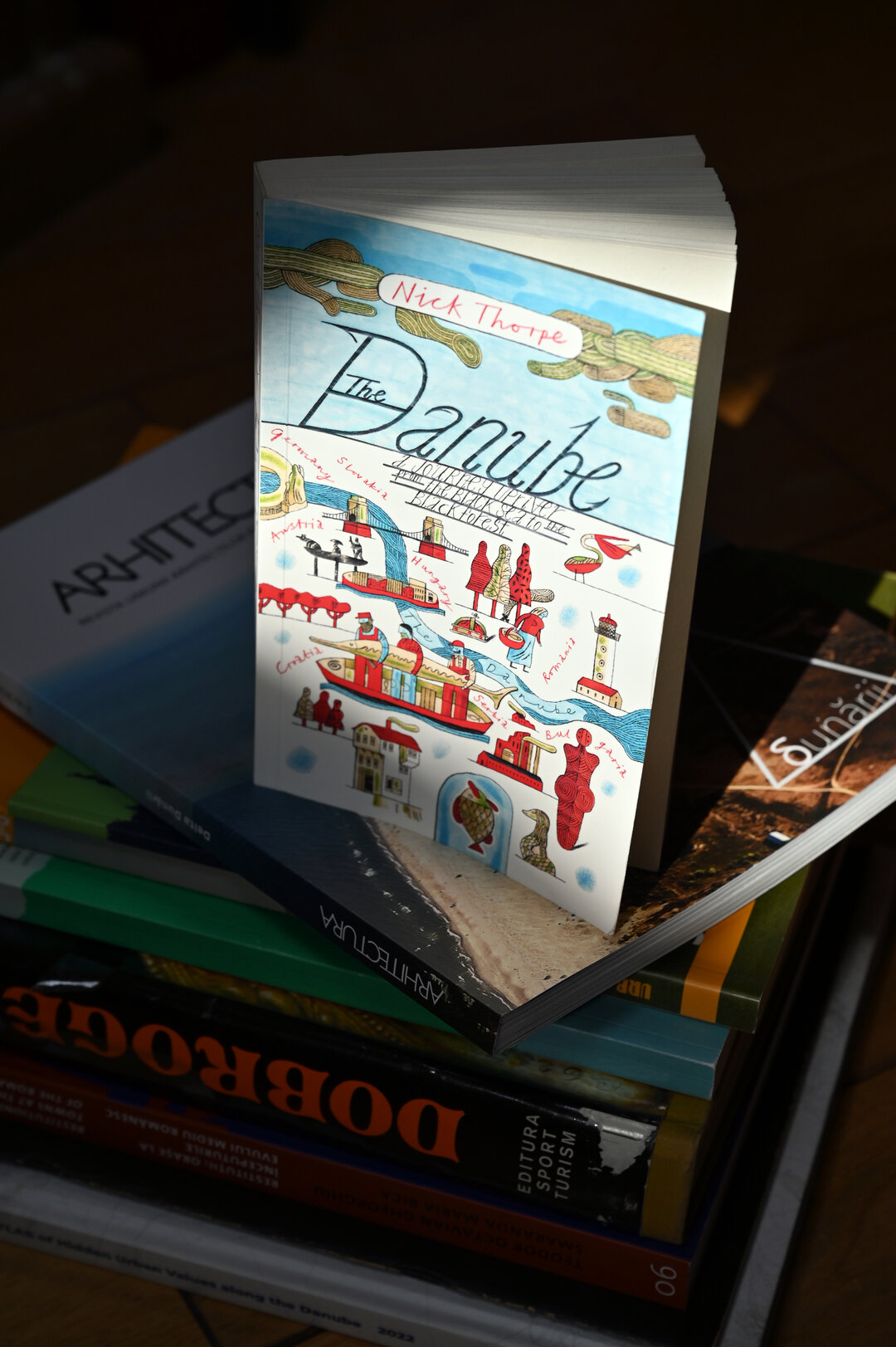

Bibliography:

Giurescu, C. C-tin.-Istoricul orașului Brăila, București, Editura Științifică, 1968

Iorga, Nicolae - Din trecutul istoric al orașului Brăila, Brăila, Editura Istros, 1999

Stoica, Maria - Brăila, memoria orașului, Editura Istros, Muzeul Brăilei, 2009

National Museum of Romanian History - Romanian Cities, late 19th- early20th century, Bucharest, Cetatea de Scaun Publishing House, 2008

Album Brăila modernă, illustrated postcards, V. Avramescu, Brăila, Ed. Istros, 2006

-topaz-denoise-enhance-sharpen--15883-m.jpg)