Back to the Danube

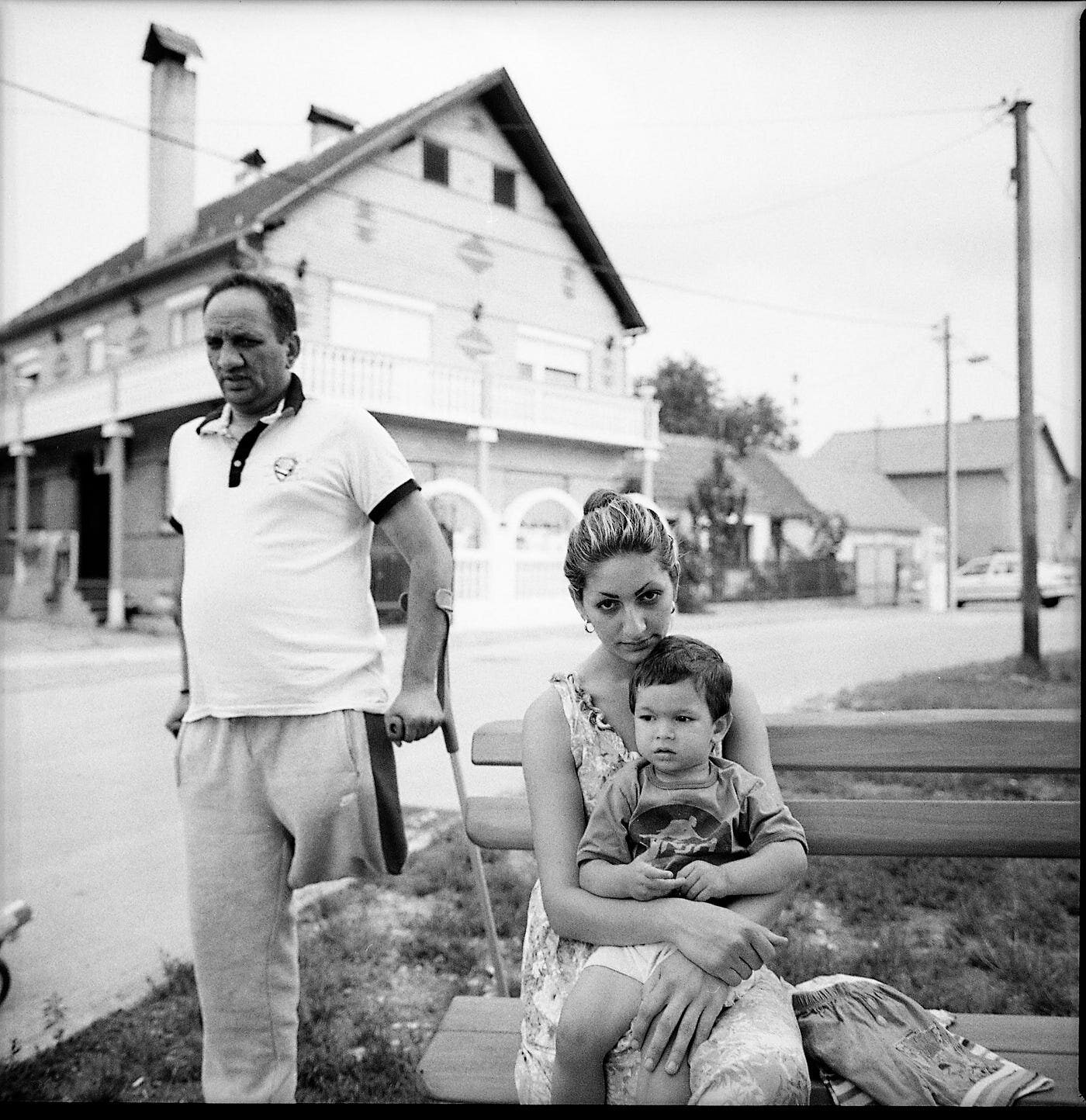

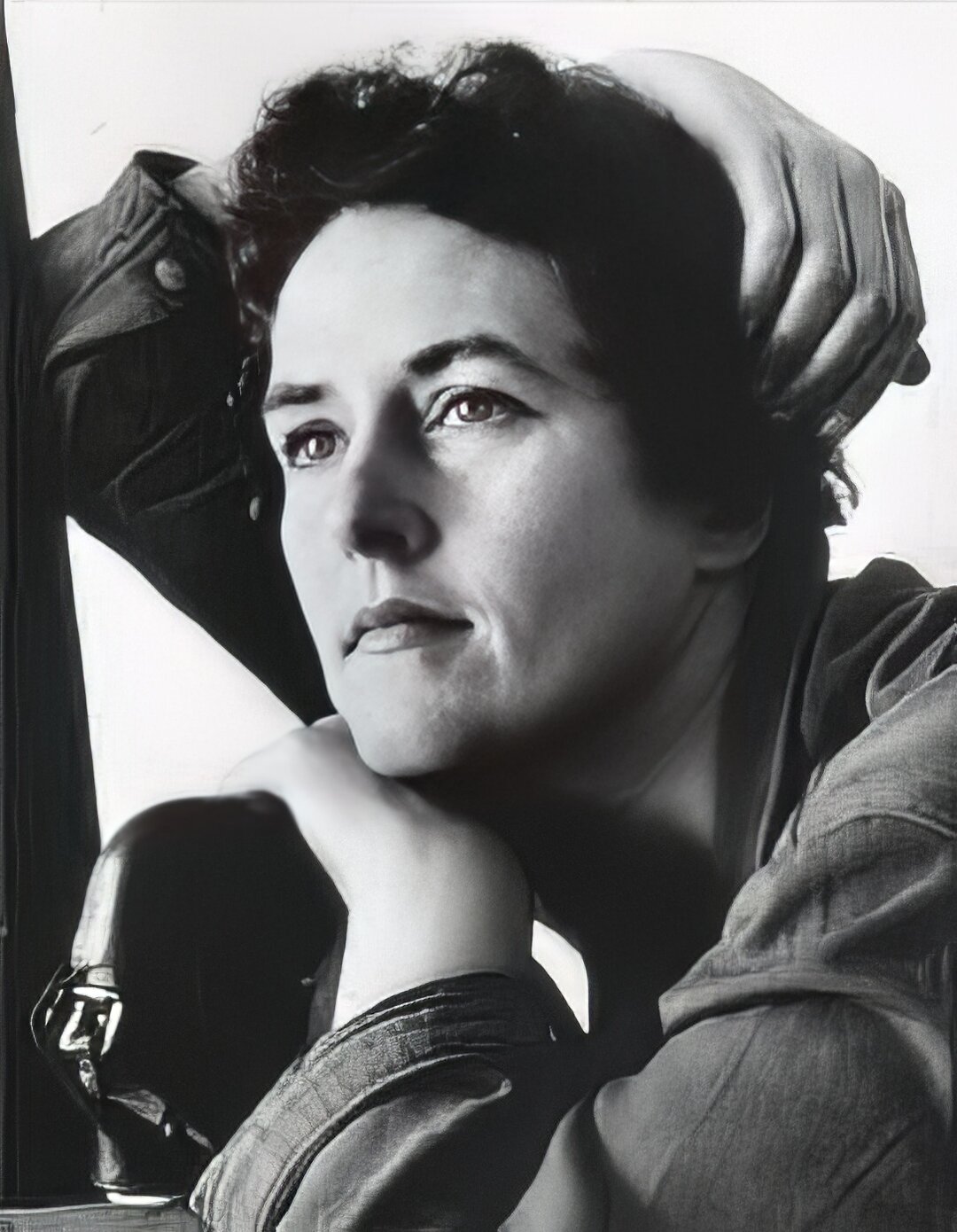

© Lurdes R. Basoli

Danube revisited

Donaueschingen

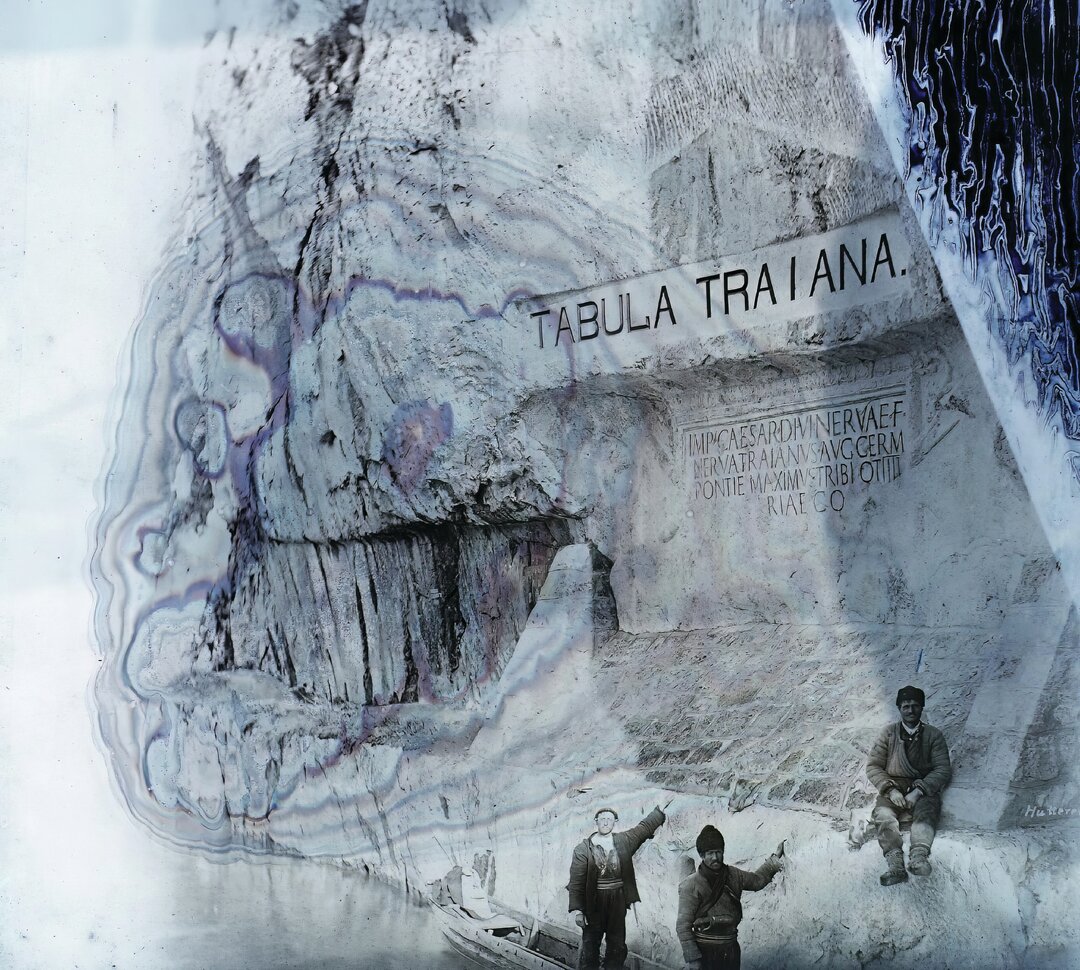

It's raining in the public park of Donaueschingen in the Black Forest mountains of Germany. It's not a heavy downpour, but a light, barely audible drizzle, a watery mist that does little to drown out the bird calls. A woodpecker chattering restlessly, a woodpecker sending Morse signals. The forked paths go deeper into the forest, along the ferns, through lindens, spruces and oaks. They pass a memorial stone inscribed "We shall not forget. 1939-1945", and a large pond with swans and ducks. After a while, the trees disappear, giving way to an outdoor sports complex with tennis courts and a soccer field, now empty because of the harsh weather. I keep walking until I come to a gravel path, glistening with damp, my coat and shoes completely wet, until the park's terrain begins to narrow on both sides, culminating in a triangular point, like the bow of a ship. This is where two small rivers, the Brigach and the Breg, join together to travel together nearly 3,000 kilometers across Europe, all the way to the Black Sea. It is the birthplace of the Danube, the childhood cradle of an ancient river.

Having spent much of my childhood in a Bulgarian village on the banks of the Danube, where it flows silently like a cloud, almost a kilometer wide, I always wondered what lies upstream and where so much water could come from. My grandfather had told me that its source was in a remote place called Schwartzwald, or the Black Forest, in Germany. My grandmother told me that Hansel and Gretel and Little Red Riding Hood and Snow White lived there. And so the Danube became for me the river that linked this world to the world of fairy tales, the magical passage between reality and fantasy, and if one caught a glimpse of the Danube, or sailed westward, and went far enough, one would at some point cross an invisible border, or portal, into another universe, filled with gingerbread houses, witches and talking animals. This, I realize now, is how the ancient Greeks - Herodotus, Strabo, Pliny the Elder - looked at the Danube: its unknown source was a source of mystery and wonder, and was believed to be somewhere in the mythical realms of the Hyperboreans or in the realm of Hesperia, which no one had ever seen. Even the German cartographer Sebastian Munster, as recently as the 16th century, surmised that the Danube was probably formed by the retreat of Noah's flood. The "River of the Gods" is the term later used by the Romantic poet Hölderlin to describe it.

And, indeed, is the Danube not unearthly, such a tangled mixture of water and myth that it is nowadays completely impossible to tell where one begins and the other ends? There is no other river on our planet that has been so radically transformed by the human mind, literally and figuratively: cursed, directed, redirected, adorned with history, with novels, with poetry and philosophy, politics and religion, with architecture, paintings, photographs, with artificial fertilizers and sewage systems, legends, fairy tales. The Danube is, in fact, not so much a river as a space of the imagination. To dip your hands in its waters is perhaps to come as close as possible to the physical touch of thought.

And now that I am at its source after all these years of plotting, seeing the source of the river in all its most mundane, prosaic - a scant river, its surroundings crisscrossed by power lines and a hideous concrete highway bridge, all shrouded in a gray haze - surely must bring me back to reality, but somehow the memories won't let go, and I have a strange feeling that at any moment a wolf disguised as a grandmother or a singing dwarf armed with a lantern and a pickaxe might appear from the bushes.

I know it's not just me. I know that, on the same day, photographer Kathryn Cook is wandering somewhere in the Black Forest near Martinskapelle, 50 kilometers from where I am, with her two small children in tow, trying to capture something of the atmosphere of Grimm's fairy tales through the lens of her camera. For isn't art, in the end, just an attempt to see the world through the eyes of our younger, more miraculous past selves?

Regensburg

It's still early in the morning, but Regensburg's old waterfront is already buzzing with noise and movement, with luxury cruise liners docking one after another. Amasonata, Avalon Poetry, Kristallprinzessin, Kristallkonigin: the names of the ships are all fantasy and clink of clink ("made exclusively with Swarovski elements"), elegance and waltz. Their two-tiered silhouettes are slender, chubby, almost friable, dotted on either side with continuous rows of glass-walled cabins overlooking the river, like a series of small theater stages. Some staterooms have heavy tulle curtains drawn back, but others lie uncovered before the viewer's wandering eye, revealing sumptuous contents: queen beds and writing desks, bottles of wine in ice-frosted frapiere next to tall, half-empty glasses. On the lower deck there are usually spacious dining rooms, with ornate interiors, silverware already carefully arranged on round tables awaiting lunch, and adjoining piano bars, dark-paneled and diffusely lit, their shelves stacked with colorful bottles.

It's the kind of world that piques photographer Lurdes Basoli's interest: the non-authentic, substitutable, anonymously consumerist world that often resembles a shopping center or a hotel. "I'm drawn to the non-romantic side of the Danube, the impersonal places, and I'd like the viewer to be unable to guess where the photograph was taken," she tells me as we walk along the Regensburg waterfront of the river, and she points her camera this way and that. "I want to photograph people who have lost touch with the river and are carried away by its inertia."

No doubt, there's plenty of inertia here. The Danube cruise ship industry knows how to sell the exhausted European myth to paying customers, mostly white retirees from Britain, the United States and Australia, eager to visit the places they may have read about in childhood, the medieval abbeys and neoclassical palaces, the bizarre ruins of long-gone empires, to see famous paintings by famous painters while listening to Richard Strauss in the background. It is a desperate attempt, after a life spent behind a desk, to get closer to what is supposed to be genuine culture and refinement, to come into contact with the gold-polished centre of "civilization", and then, once back home, to flaunt their newly acquired status with smug pride in front of friends and relatives. Or perhaps it is much simpler than that: the need to fill the endless hours of post-retirement loneliness, to distract oneself, with lively sounds and images, from the dreadful and ever nearer approach of death.

There is something endlessly sad in this picture of elderly pilgrims disembarking from cruise ships at Regensburg, dressed in safari shirts, khaki shorts and wearing baseball caps, old-fashioned dresses and wide-brimmed hats, limping hesitantly down the walkway, many of them carrying walking sticks or even frames, with earphones and wireless receivers hanging from their necks - the ruins of the Anglo-Saxon world strolling among the ruins of Mitteleuropa. Only the group guides are young and energetic, leading the way into the medieval city center, jabbering incessantly into tiny microphones and offering information about the old gabled merchants' houses and Gothic cathedrals. "The city is very safe, so sit tight," I hear one of them say, "just watch out for bumpy sidewalks and bicyclists."

And suddenly it all makes sense: the cruise ships are, in fact, a kind of floating "coffins" on the Danube, carrying their passengers on a journey on this side of the river for one last time.

Mauthausen

When Emily Schiffer was in the third grade, she learned about the Holocaust from her two best friends, who had learned about it in Jewish school. They shared horrifying details with Emily, and the three of them invented a game, an early exercise in processing history. They pretended to be prisoners of the Nazis and were forced to drag heavy cement blocks by their chains under the watchful eyes of the guards, who whipped them mercilessly every time they slowed down. Although Emily was only half-Jewish, her friends assured her that the Nazis would not spare her. "The fact that they would have killed me, too, was strangely comforting," she tells me as we drive to the Mauthausen concentration camp museum in northern Austria, about 20 kilometers from the city of Linz. "It gave me a sense of belonging."

It's a perfect July day, warm and clear, and there are four of us in the car: Emily, her little girl named Lola, Emily's former photography student - Jessie, and me. Finding Mauthausen turns out to be not so easy, with only a few blurry signposts to guide us, as if Austria herself wants the dark secret in her heart to remain buried. Only a McDrive in Mauthausen suggests, absurdly, that we're on the right track.

After a short drive along a winding wooded road, we finally reach our destination. Hidden amid bucolic green hills near the Danube, Mauthausen looks by far like any other medieval castle: thick walls of gray granite, solid towers, massive main gates. As we approach, an eerie sense of pressure settles over us all, as if the very air has been soaked in lead. The spirits of the dead cling to your back, your hands, your feet, your skin, like drowning victims desperate for air.

Between 1938 and 1945, more than 120,000 people were killed here in one of the most notorious Nazi concentration camps. Marked grade III, the worst possible, Mauthausen was reserved for "incorrigible political enemies of the Reich", mostly artists, scientists, priests and activists. Many of the prisoners were used as slaves in the granite quarries just beyond the camp, where they toiled 12 hours a day in appalling conditions, malnourished, beaten until they collapsed from exhaustion. The 186 steps known as the "Steps of Death" climbed from the quarry to the camp, and exhausted prisoners, carrying stones weighing up to 50 kilograms on their backs, often lost their balance and fell, dragging those behind them in a domino effect. Others were lined up at the top of the steps, on the edge of the cliff called the Parachute Wall, and given the choice of being shot or pushing down the one in front of them.

"So I didn't make up the part about dragging cement blocks," Emily says as we glimpse the quarries at Mauthausen. "Except it was granite, not cement."

On the day of our visit, Mauthausen is almost empty, with only a few tourists strolling around idly. With the massive Hasselblad camera slung over her shoulder and Lola in her fanny pack, Emily vaguely resembles one of those equipment-laden American soldiers who liberated the camp in May 1945. Coming to Mauthausen is her way of revisiting her childhood fantasies, her nightmares, of breaking free.

But Jessie Carlson, Emily's photography student, is the most troubled. A member of the Lakota people of the town of Dupree, on the Cheyenne River Reservation in South Dakota, she is traveling outside the United States for the first time. In her pink shirt and electric blue jeans, she looks like any energetic young woman, but deep down she carries the burden of her tribe's past. Her great-great-grandmother was a survivor of the Wounded Knee Massacre, where hundreds of Lakota members were killed by the U.S. Army in 1890. Jessie knows firsthand the agony that racial politics and colonialism inflict on individuals and culture - and how hard it is to right that wrong. So when she sees the Mauthausen exhibits, she has an epiphany. This is her history - her story.

"In the Lakota language there's a word, wanagi, when you're in the presence of the spirits and it gives you chills," Jessie says. "That's exactly what I'm feeling right now, wanagi. I get cold in the sun."

"There are a lot of spirits around," Emily nods, as she tries to soothe her baby, who has started crying. "Do you think Lola senses something too?"

"Yeah," Jessie says.

We walk around Mauthausen for a couple more hours, looking at photos, memorials, historical markers. There's an exhibit showing a mining cart from the granite quarry and a whip used by the guards - just like the whip that appeared in Emily's role-playing games. At the end of the day, we go down to the basement, where the gas chambers, disguised as shower rooms, and the crematorium were located. Up to 120 people were being killed there at any one time. A heavy and voluminous register, containing the names of all known victims of the camp, sits on a table in the black vestibule. Emily finds four people with the name Schiffer listed, but she doesn't know if they were related.

Suddenly, Lola starts crying again, her voice rising into a scream. This place, ha haunted by so much suffering and death, so much pain, is no place for a child, so we quickly pass through the gas chambers and head for the exit.

"Here we are, on this beautiful day, in this awful place, and I wonder where the memory goes," Emily whispers, as if to herself. "Does it go into the walls? I used to ask my mother if the walls remember their former inhabitants, but I don't think she understood what I meant."

Zebegeny

It's late afternoon in the village of Zebegény, and a small blue Mitsubishi tractor pulls a utility trailer full of chairs. It cradles across a visitors' parking lot, in the dappled shade of plane trees, and slowly descends towards the stony bank of the Danube, where it finally comes to a stop. The driver gets out and begins unloading the chairs, while another man helps arrange them in neat rows right by the water's edge. In another 15 minutes or so, everything is ready, and the guests take their seats one by one, eager to witness the wedding of Zsófia Pályi and Bálint Hirling.

Few places in Hungary are more romantic than Zebegény. Here, the Danube stretches wide and languidly around a majestic bend, dizzy in the summer heat, meandering through a landscape of rolling green hills, vineyards and orchards, where only the overflowing cries of splashing children and the occasional rumble of a motorboat interrupt the liquefied silence. Immortalized in bright watercolors by local artist István Szőnyi, Zebegény has now become a favorite Hungarian hangout, a quick escape from the hustle and bustle of Budapest. On weekends and vacations, many come here to swim, go boating, or just take a stroll along the Danube bank. It is also, if so inclined, the perfect place to get married. When Zsófia, the Hungarian documentary photographer we met in Budapest, extended a surprise invitation to her wedding, Olivia Arthur was delighted, as her own project, Danube Revisited, deals with precisely this subject: love. I offered to join Olivia, and we both jumped in my Ford Fiesta and drove 60 kilometers from Budapest to Zebegény. I hadn't prepared a present, so on the way we stopped by an open field and picked a bunch of wild wild flowers for the (future) newlyweds. "It's great to be a wedding photographer, everyone welcomes you," Olivia told me in the car, delighted at the prospect, and recalled how at her own wedding some time ago, a friend of hers had taken over 3,500 photos. Now, married and four months pregnant, it was her turn to once again stand behind the camera, and Zsófía's turn to stand in front of it. Photographing photographers, or writing about writers, has always been a philosophical matter, at once intimate and intimidating.

As the sun begins to set, the wedding ceremony on the banks of the Danube begins: the perfect light for Olivia and her large Pantax camera. The guests' seats are slightly tilted at an angle along the sloping bank, and they all look like passengers on an airplane changing direction. Sitting in front of them, Zsófia is wearing a blue-print summer dress and large brown ball earrings, while Bálint is dressed in a white shirt with a blue pattern, blue pants and brown shoes with blue laces. From a certain angle, they both seem to merge into the clear sky, like two happy ghosts. The mayor of Zebegény, an elegant, middle-aged woman with glasses, officiates in the place of the Catholic priest, reading aloud from a red-colored notebook.

"Do you, Bálint Hirling, take Zsófia Pályi to wife? Do you promise to be faithful to her in good and evil, to love and honor her all the days of your life?"

"Yes!"

"Do you, Zsófia Pályi, take Bálint Hirling to be your wife? Do you promise to be faithful to him in good will and in evil, to love and honor him all the days of your life?"

"Yes!"

Moments later the couple kiss and a bottle of champagne is opened. That was it: two rivers that have willingly joined their waters, merged completely, to continue their flow together across the unexplored landscape of life, through plains and cities, sun and rain, towards that distant and ultimate sea, which hopefully is still far away from everything, invisible beyond the horizon.

Novi Sad

Mile Jovanović lives in Shanghai, or Šangaj as the locals call it. At 40-something, she already has a balding start and a full belly. Today is Sunday, a lazy Sunday at the end of July, and he's lounging on a wicker chair under the shade of a cypress tree in front of his house. He's not wearing a shirt and is barefoot, which is to say he's not wearing a shoe on one foot. On the table in front of them is a plate of pancakes with apricot jam and a glass of homemade lemonade.

This is what Sundays must look like.

When Claire and I approach Mile, she warmly invites us to join her. "Have some pancakes," he says and pushes the plate toward us. We gratefully accept his gifts, glad to be out of the scorching sun for a few minutes.

Šangaj is a suburb of the Serbian city of Novi Sad, on the north side of the Danube, tucked between an oil refinery and the slender white-red furnaces of a power plant. Years ago, a Chinese man lived in the area, and when he died, the name somehow stuck. Shanghai. Today, it's home to nearly 2,000 people, mostly Roma but also ethnic Serbs, Hungarians and Albanians. For centuries, Europe's Roma were persecuted and excluded, vilified and demonized, forced to live in ghettos and slums without running water or electricity, but here the atmosphere is very different. The streets are well paved and clean, flanked by large, solid houses, many of them freshly plastered. There's a pharmacy, a school, a youth center and playground, and a brand-new library. A soccer field with immaculately mown lawn stretches towards the river. It is far from affluent, but it is home to a strong, close-knit community that defies easy stereotypes. When the decision was made to build a new church a few years ago, everyone pitched in, whether Roma, Serbs, Christians or Muslims.

"As Roma, we have no problems here," Mile tells me. "Everybody looks after everybody. Elsewhere, we face a lot of discrimination, but not in Šangaj."

Over the years, Mile has managed to build a comfortable middle-class life for himself and his family. Coming from a merchant family, he set up a company that transports coal and firewood by truck in the Novi Sad region, and now has three trucks and five employees. The business has done well, as the yellow-red brick, gabled, two-storey house behind him confirms. Together with his wife, Ruža, a beautician, he has four daughters and three grandchildren, all of whom lead a comfortable existence. He really has nothing to complain about. Except one thing.

I work up the courage to ask Mile about his leg. How did he lose it? Was it an accident?

He looks at me with a vague smile. In 1991, when he was just 19, civil war broke out in Yugoslavia and he was conscripted to fight in Croatia. Soon after, his military truck was hit by a tank shell and Mile lost his left thigh leg. "What was the point of the war?" he asks and then quickly adds, as if to himself: "None. There was no point. We fought our brothers for nothing."

But the war never really stopped. In 1999, during the NATO bombing campaign of Yugoslavia, planes targeted the neighboring oil refinery, the blast so powerful it shattered all the windows in Mile's house. After that, the incidence of cancer in the neighborhood rose, possibly from chemicals in the air, possibly from the depleted uranium used in the bombs.

Today, all Mile wants is the peace of sitting in the shade of the cypress and eating apricot jam pancakes. I take a bite of the pancake and immediately understand what she means.

Dolni Vadin

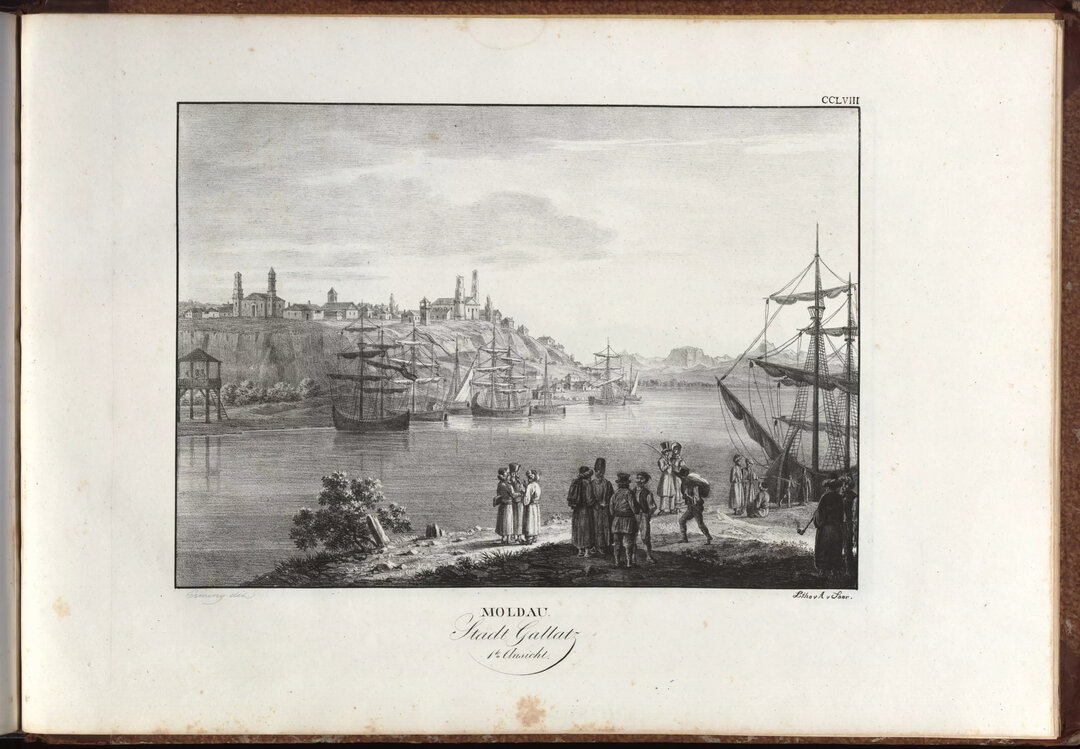

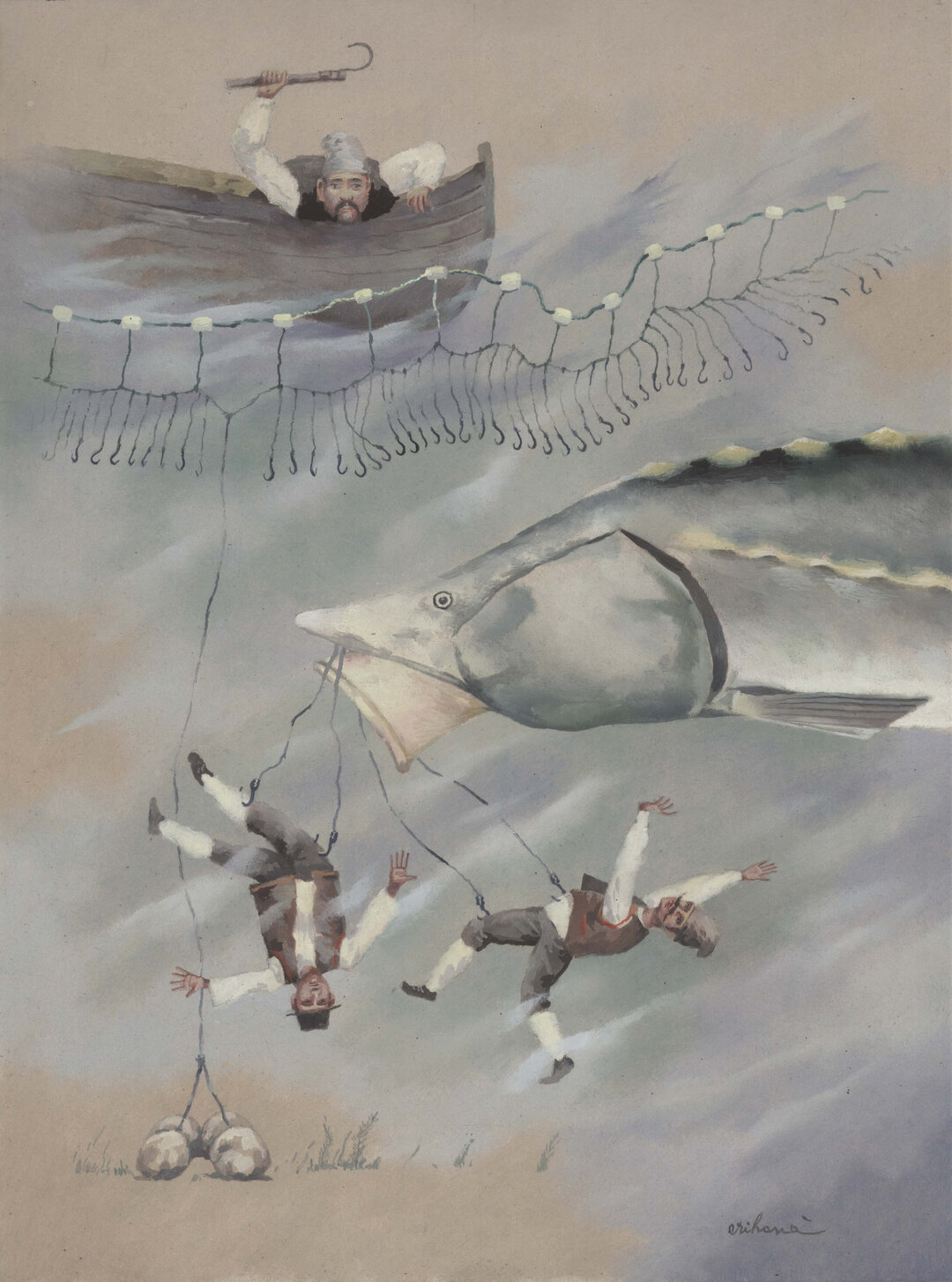

Every morning, shortly after sunrise, Lyudmil Krastev pushes his blue-and-white fiberglass boat into the murky river. The current is strong, the water writhes and pulses beneath it like contorted muscle, impossible to face, impossible to resist, so he carefully, almost tenderly, gently, as if afraid of disturbing the tranquility of some mythical creature in the deep. At this point, near the Bulgarian village of Dolni Vadin, the Danube is wide and falconal, a mature river at the height of its power, gnashing its fangs, smashing every obstacle in its path and swallowing everything.

There is only one problem. The river's belly is empty.

When Lyudmil reaches the fish nets, he anchors the boat and slowly pulls in the catch, but there's almost nothing: a few small perch, maybe a carp or two, mixed in with dirty plastic bags and all sorts of bits of trash. Gone are the days when he used to bring home a huge sturgeon and a 100-pound catfish, as his father and grandfather had done before him. Pollution and river dams have killed most of the fish, while poachers, in cahoots with the border police, scrape the bottom, raking up and down the river with electric wires attached to large batteries, electrocuting any remaining fish en masse. "The electricians," Lyudmil calls them ironically. He would never stoop to this kind of dirty business. He likes to see the fish struggling in the net, to hold them in his hands. But the truth is, it's barely enough for him to survive, and the biggest catch he has to hand over to his "patron," the wealthy man with the big white house on top of the hill who owns the blue-and-white fiberglass boat.

Like the fish, most of Dolni Vadin's fishermen have already left, moving on to other lines of work elsewhere. Lyudmil is one of the last remaining, a lucky survivor of the ecological shipwreck. In his late 50s, in old sweatpants tucked into rubber boots and a pack of cigarettes in his shirt breast pocket, he is known locally as "Captain" because he once starred in a movie about the Danube. When Ami and I meet him on the banks of the river, he surveys us suspiciously at first, but before long he shows us the boat and talks to us about fishing, about life.

"I like it here a lot. I don't know what I'd do without this river. I've fished other places, but there's nothing like the Danube," he says and sketches a broad smile, revealing a cheerful row of crooked, yellowed teeth. "I love the utter stillness, the freedom to go out at any time, the freedom beneath the sky and the water in the deep. Sometimes there are days when you don't see a human around."

Yet his greatest suffering is pollution. Plastic bottles, plastic bags, car tires, oil spills, raw sewage. "Now everyone is throwing garbage into the river. It's disgusting," says Lyudmil. A month or so ago, on Danube Day (June 29), Lyudmil and some of his fishermen friends organized a big clean-up operation, followed by music and drinks. At the end, after collecting all the rubbish they could find and getting rid of it, they stuck a huge red sign in the sand: "Keep the river clean! It's ours!".

The place may not stay clean for long, but for now, at least, the picture seems almost bucolic: cows and goats graze peacefully on the green banks; storks fly overhead and occasionally touch the water in passing. A large, round boulder, like a moraine left by the retreat of a glacier, reminds the visitor that there was once a Roman bridge.

Despite all this, the river is still there.

Belene

As darkness falls over Belene, on the Bulgarian side of the Danube, and the crickets outside in the wild fields begin their practice for the evening concert, Raycho turns on the lights in his prison room, a single hollow bulb hanging from a cable in the ceiling, and sets the table for dinner. His gifts for us are simple but generous: a tomato, a piece of feta cheese, some sausage, bread and even halva for dessert. Claudia and I try to protest, telling him that he should save the food for himself, that we could get something to eat later, but he's adamant. We're his first guests at the prison, the first human beings he's spoken to in more than a month - "37 days, to be exact," he says - and he insists on playing the welcoming host.

The space is modestly furnished but fairly clean and neat. A rickety wooden table with four mismatched chairs, some old drawers and an individual food cupboard. Beautiful reed panels in rhomboid patterns, the persevering work of former prisoners, cover the walls from floor to ceiling, like insulation in a recording studio. Though it's late July and the nights are sweltering, Raycho keeps an old radiator running in a corner, rising at intervals to light a hand-rolled cigarette from the glowing coils in plain view.

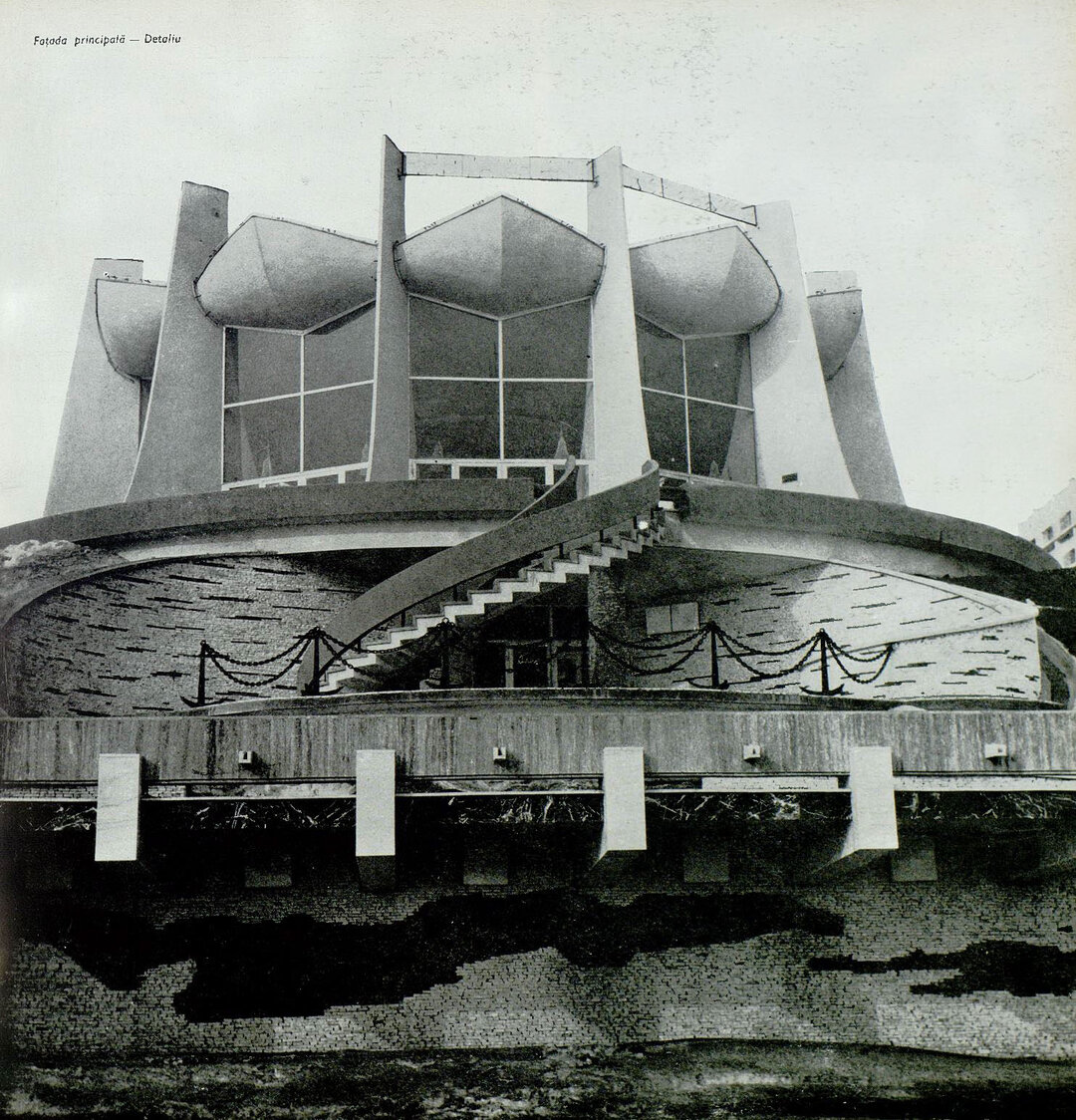

Claudia and I met Raycho by chance on the road outside, as the sun was setting, because we had gotten lost in Belene. We'd driven to the edge of town to reach an abandoned neighborhood of concrete apartments that once would have housed the workers of a future nuclear power plant. The power plant was never completed, and the workers never arrived. As the years passed, nature began to reclaim its lost territory, and today the half-finished carcasses of the four- to five-story buildings crumble amid a lush jungle of greenery, like the ruins of ancient Greek temples, with bramble overgrown from crevices and unfurling crowns of trees camouflaging the main entrances. Wild dogs are the only inhabitants here, huddled in packs on the railless terraces and howling. Belene is a lot like Chernobyl, apart from the nuclear blast - a place where the only disaster was the slow decay brought on by economic collapse.

"And who are you?" we asked Raycho, after he directed us to the apartment projects we could see glimmering in the distance across the fields. He seemed an agreeable young man, in his mid-30s, with close-cropped hair and dark eyes, dressed in a running shorts and a blue Italian national soccer team jersey.

"I'm a prisoner," he said, gesturing toward a neighboring cluster of disused buildings behind an iron fence. "But I'm the only one here. I'm guarding an abandoned prison." Then he paused, and a kind of wariness shadowed his gaze. "Would you like to come in for dinner?"

Now, sitting at the table with him and eating his tomatoes, cheese and bread together, he begins to tell us his story. He is of Bulgarian-Turkish origin and grew up in Isperih, a small provincial town in northeast Bulgaria. When he turned 18, he left to do his military service, but while he was away, his girlfriend, already eight months pregnant, was killed by a truck. "Something broke inside me when my girlfriend died," Raycho says. "My life spiraled out of control." When he got out of the military, he worked construction for a while, worked at a casino, pimped pimps. He often got into brawls and knife fights, earning the nickname Mad Max. One night, while driving drunk, a local cop pulled him over, but instead of trying to dodge, Raycho got into a violent altercation with the officer. And since he was on probation for drunk driving, the judge sentenced him to three years on the Danube island of Persin across the Danube from Belene - the site of a horrific communist-era labor camp now operating as a regular prison.

However, while at Persin, Raycho tried to go straight. He became a model prisoner and soon became popular with the guards. After serving a couple months of his sentence, he was sent to guard an abandoned prison unit on the outskirts of Belene, once a division of the main prison on Persin. He converted one of the old administrative offices into a living space and settled in, patrolling the surroundings during the day and trying to keep out would-be thieves of building materials. From time to time, someone comes to bring him food supplies. Raycho is obliged to stay within the prison's perimeter and to occasionally contact his superiors through a walkie-talkie, apart from this there are no other restrictions. He is a prisoner guarding his own prison.

After we finish dinner, he clears the table and Claudia starts taking pictures. I explain that we are traveling down the Danube, documenting life on the river, and she wants to be as helpful as possible. She poses naturally, with no visible signs of discomfort. He leads us into a small adjoining space, separated by a diaphanous white curtain, where he has laid out a narrow bed, its sheets smoothed with military precision. A small, oval mirror, a few simple pen-and-ink drawings on loose sheets of paper (a horse raised on its hind legs; a woman smelling a red rose), and several magazine clippings of nude women decorate the bare cell walls. It might as well be Robinson Crusoe.

"Solitude is hard sometimes," he tells us, "but I think it's good for me. It lets me think about my life, what I've done. All I want to do is start again when I get out, somewhere far away from here, far away from Bulgaria. I'm done with this country."

It's getting late and Claudia and I have to get back to the hotel. Raycho reluctantly leads us to the main gate and hugs us goodbye. The dark vault of sky above us is serene and huge, bathed with bright summer stars. Fireflies blink in the fields around us, like miniature paradises. Freedom is everywhere and nowhere.

"If you're still here tomorrow," says Raycho, "bring me some tobacco and rolling papers. And soap would be good. And a shaving kit. I'd like to imagine that, somewhere, someone is thinking of me."

Then he goes back into the prison, closes the gate behind him and turns the key.

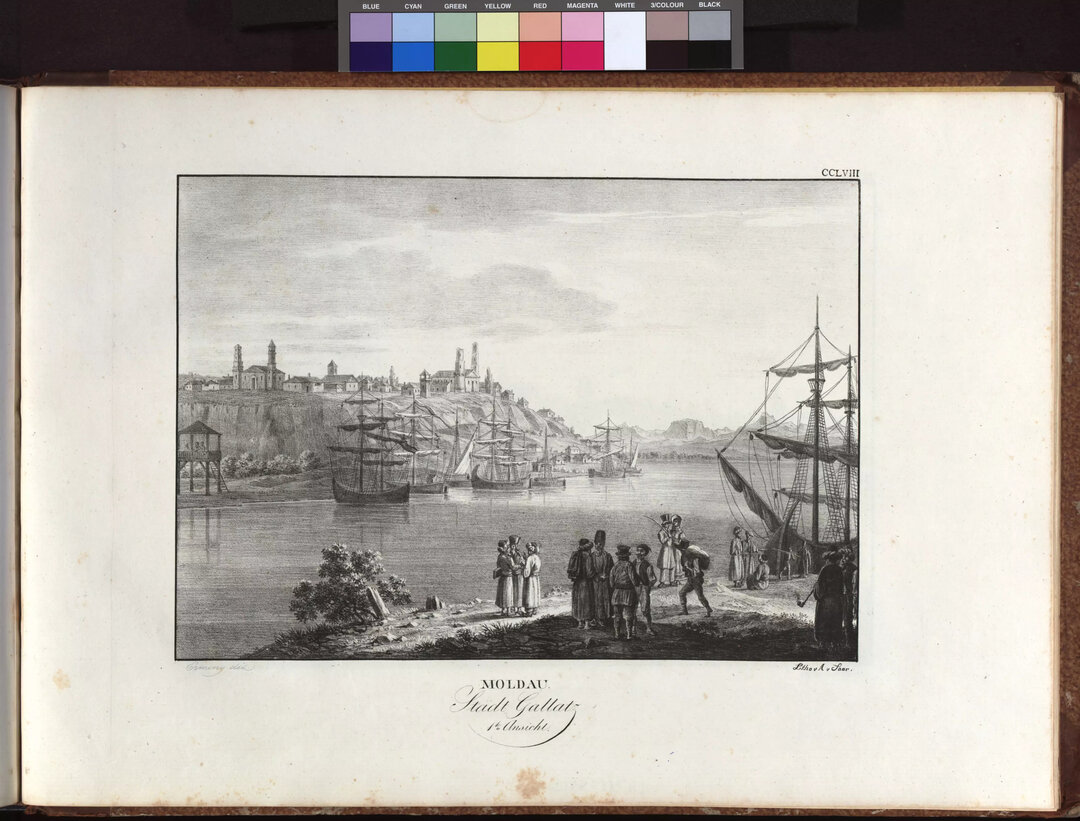

Sulina

When the world ends, it will look like Sulina.

This is the Danube's last stop, its deathbed, before it merges with the boundless ancestral waters of the sea, but also the place where the river shines in all its splendor and is most alive. Amid the lofty thickets of the wide-spreading sea-deltas, among the canals, marshes and lakes, wild beasts swim and fly, pike and catfish lurk in fearful ambushes through the depths, dwarf cormorants dive from the heights of the sky, and great flocks of white pelicans soar up from the water's surface, picking up speed, flapping their wings in a deafening din, like the noisy crowds in football stadiums, until suddenly, in flight and silence, graceful giants, unmoved by the earth's grim gravity, reappear.

In this paradise of abundance, Sulina - a post-industrial town of one-storey houses and peeling paint, abandoned fish-processing factories and old shipyards full of rotting ship hulls, once the headquarters of the European Danube Commission in charge of regulating river traffic - you might feel out of place, a human scourge on the surface of the river, but decrepitude itself seems somehow fitting, holding out the promise that the end of mankind does not necessarily mean the end of time, that human graves are just more fertile seeds sown in the endless womb of nature.

"I'm not into this nature stuff," Jessica Dimmock tells me when we first arrive in Sulina. Originally from New York City, dressed in a dark blue overalls like a skilled mechanic, dark circles under her dark eyes, she looks bored on the boat ride we take through the marshes and lakes of the delta, bored by the guide who shows us, with childlike delight, the various types of birds. But the remains left behind by people fascinate her, and one day we decide to go and visit an old abandoned metal workshop near the shipyards, across the Sulina canal. It's a large warehouse of cinder cement blocks, with crumbling concrete pillars supporting a crumbling concrete roof, with many of the side windows broken, letting the bright sunlight in, warm and unaltered. Inside, strewn in disarray on the dirt-covered floor, lathes, bellows and gearwheels that must once have roared and clattered with life, tossing off metal parts for the ships that sailed the Danube. Nothing clangs now, and our voices echo in the cavernous space, the only living things in this machine graveyard.

And then we notice the horse manure. It's everywhere, in piles like little mounds of stones, and it seems fresh, its faint, slightly sweet odor wafting through the stale air. So the old philosophers were right after all - nature abhors a vacuum, it reuses everything in its own way, and this abandoned workshop may still have a purpose, may still serve as a home for homeless creatures, even if all its former inhabitants have long since departed.

When Jessica and I go outside, we see them in the field. Horses! A herd of a dozen or so, grazing quietly along the riverbank, next to the useless rusting railroad tracks wrapped in fresh grass. Their robes are black and shiny, with coats spilling down their necks like the wild locks of old warriors. We try to approach them silently, but they pop their heads up and look at us alarmed, ready to bolt. Jessica looks at them through the camera lens and takes a few snapshots, trying to immortalize them in time. But time won't stand still. The horses, sensing danger, start galloping across the fields along the Danube bank, first slowly, then faster, the river and the horses suddenly becoming one, flowing, rushing, endlessly.

When all the cameras break and all the photographs are forgotten and lost, the river will continue to flow on, oblivious to memory and our feeble attempts to preserve it.

****

Dimiter Kenarov is a freelance writer based in Sofia, Bulgaria. He has written for The Atlantic, The Nation, The New Yorker, The Virginia Quarterly Review and several other publications.

Kathryn Cook grew up in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and graduated from the University of Colorado Boulder in December 2001. Her work has appeared in numerous publications such as The New York Times Magazine, Time, Stern, Newsweek, Newsweek, L'Espresso, and D - La Repubblica delle donne.

Lurdes R. Basolí is a Catalan photographer based in Barcelona and San Sebastián. She has published in magazines such as El País Semanal, The Sunday Times Magazine and Internazionale or Photo Magazine.

Emily Schiffer is a mixed media photographer and artist living in South Dakota who is interested in the intersection of art, community engagement and social change.

Olivia Arthur is a British documentary photographer based in London. Her photographic albums include Jeddah Diary (2012) and Stranger (2015), and in 2020 she was elected President of the Magnum Photos Agency.

Claire Martin lives in Perth, Western Australia and is a freelance photographer and documentary artist for socially engaged projects. Her work has been rewarded with a Prix Pictet nomination (2012), a Lead Academy Award (2011) and an IPA nomination (2008).

Ami Vitale is a contract photographer, filmmaker, writer and explorer for National Geographic. She has documented wildlife and poaching in East Africa, tackled the human-elephant conflict, and focused on efforts to save the northern white rhino and reintroduce pandas back into the wild. She is also the winner of six World Press Photo awards.

Claudia Guadarrama is a documentary photographer based in Mexico who focuses on political and social issues in Latin America. Her work has appeared in The New Yorker, Smithsonian Journeys, GEO France, TIME, El Pais, Paris Match, L'Equipe, Le Monde and The Guardian, among others.

Jessica Dimmock is a Brooklyn-based documentary photojournalist and filmmaker. Her work has been published in Aperture, The New York Times Magazine and Newsweek, among others. She has won numerous international awards for her photography and video work, including two World Press Photo Digital Storytelling Awards. He co-directed the critically acclaimed Netflix documentary series Flint Town.

-topaz-denoise-enhance-sharpen--15883-m.jpg)